VEIN CONSULT Program: interim results from the first 70 000 screened patients in 13 countries

ABSTRACT

The VEIN CONSULT Program, a joint initiative between the Union Internationale de Phlébologie and Servier, is the largest global effort to raise awareness of chronic venous disease (CVD) among patients, health care professionals, and health authorities. The aim is to update information on the prevalence of primary CVD in different geographic areas, to compare the management of the disease between countries, and to improve our understanding of the relationship between general practitioners and venous specialists, in order to propose a straightforward approach to earlier diagnosis. The survey was conducted in primary care centers as face-to-face interviews. Questionnaires were completed by practitioners and established the subjects’ characteristics and risk factors for venous disease. Complaints likely to be of venous origin and when they were most likely to occur were reported together with the presence of visible signs on the legs. All data were pooled according to geographic area. Thirteen countries have already completed the survey, in Eastern Europe, Western Europe, South and Latin America (Brazil, Mexico), and the Middle and Far East, totaling almost 70 000 patients.

Primary care patients were mostly women (>66%) except in Pakistan (48%) and were older in Europe (mean age >52 years) than in the other geographic areas (≤45 years). A majority (>60%) said they had a maternal history of primary CVD and around 10% had a personal history of venous thrombosis. Reported symptoms in order of importance were heaviness, pain, sensation of swelling, and night cramps, and were found to intensify mainly at the end of the day or after prolonged standing. Symptoms significantly increased with age and with severity of disease.

Most screened subjects (>52%) believed they had leg problems at the time of consultation, while 19% to 26% presented spontaneously for venous care. After examination of the legs by physicians, it appeared that more than 61% of subjects had visible signs on at least one leg. Around 17% of themcomplained of venous symptoms only. Patients consulting specially for venous problems had more severe signs compared with the whole sample.

Regarding costs, it appeared that CVD is responsible for large productivity losses, as well as the physical and psychological suffering of patients, which is reflected in worsened quality of life.

THE NEED FOR THE VEIN CONSULT PROGRAM

CVD is a common condition that has a significant impact on both the individuals affected and the health care system. It is estimated that 30%-35% of the general population are categorized as C0 and C1 of the CEAP classification system. This includes people with venous symptoms but no visible or palpable signs of venous disease (C0S) and those with telangiectasias or reticular veins.1,2 One epidemiological study in Germany found that only 10% of the population was free of some form of CVD.3 According to epidemiological studies over 10 years, varicose veins affect 30% of adult women and 15% of men.4 In Europe, venous disorders may affect 25% to 50% of people, for all types and degrees of varicose veins, 10% to 15% for marked varicose veins, and 5% to 15% for more severe stages of the disease.5 In countries with developed health care systems, CVD has been estimated to account for 1 to 3% of the total health care budgets,6 and the annual direct plus indirect costs of CVD in Germany, France, and the UK are approximately 800 million euros in each country.7 CVD is no longer considered a disorder related to age as the first symptoms can develop between the ages of 15 and 25 years. CVD is associated with a reduced quality of life.8 Despite being such an expensive disease with high levels of morbidity, few people recognize that early diagnosis, patient monitoring, and treatment of CVD can prevent diseaserelated complications.

AIMS OF THE VEIN CONSULT PROGRAM

The VEIN CONSULT Program is the greatest global effort to raise awareness about CVD among patients, health care professionals, and health authorities. It aims to assess the prevalence of CVD and to provide a picture of the typical adult patient and the management of their disease, in varying geographical areas. This will help to evaluate how general practitioners (GPs) and venous specialists manage patients with CVD and to understand better at which stage of the disease specialists take over from GPs in the management process.

The program is designed to detect CVD early, with the goal of improving the management process of this chronic disease, and to assess the impact of CVD on the quality of life of patients, health care resources, and the economy (eg, number of work days lost).

VEIN CONSULT PROGRAM METHODOLOGY

In Step 1 of the program, GPs screen patients consulting them for any medical reason (except an emergency). The GPs must assess whether the patients are suitable for involvement in the program using set criteria: men or women over 18 years old, informed of their involvement in a screening program and who agree to take part; informed that they have the right to refuse to participate fully or partly; not consulting for an emergency or for an acute episode of an ongoing event. The patients need to be enrolled consecutively within a short period of time.

If the patient meets these criteria, each participating GP then completes a case report form assessing the patient’s history, listing any CVD risk factors, screening for CVD symptoms, and performing a routine leg examination. If the patient shows symptoms or signs of CVD and the GP considers him or her to be eligible to participate in Step 2 of the program, the patient is asked to complete a short, self-administered quality-of-life questionnaire— the ChronIc Venous Insufficiency Questionnaire-14 (CIVIQ-14), a 14-item questionnaire. The GP then recommends a follow-up consultation with a venous specialist.

Step 2 is the follow-up consultation with a venous specialist. The specialist completes a 21-item questionnaire to establish the patient’s history of CVD and risk factors, carries out a lower leg examination, and assesses whether treatment is required.

FIRST RESULTS FROM THE VEIN CONSULT

PROGRAM

Results for the first 13 countries participating in the VEIN CONSULT Program were pooled (out of the 20participating in total) by geographical region, as patient profiles varied from one region to another. These were Western Europe (France, Spain), Eastern Europe (Georgia, Hungary, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia), Latin and Central America (Brazil, Mexico), and the Middle and Far East (Emirates, Pakistan, Singapore). Sample size varied from one region to another. Western Europe totaled 36 004 subjects, Eastern Europe had 23 412 subjects, while there were 6385 and 4065 subjects, respectively, in Latin and Central America and the Middle and Far East. A total of 69 866 subjects were screened between October 2009 and March 2011.

The mean age of patients consulting for CVD was 51.6 years. Mean age decreased across regions as follows: Eastern Europe, 53.4 years > Western Europe, 52.5 years > Central and Latin America, 46.2 years > Middle and Far East, 39.4 years. On the latter continent, Pakistan influenced the results with a higher proportion of young men.

On average, the percentage of women consulting was 67.8%, the number of women being 2.5- to 3-fold higher than the number of men, with the exception of the Middle and Far East where there were 52.8% women.

Almost 42% of subjects remembered a family problem of reticular veins, varicose veins, swollen legs, or venous ulcer. Whatever the continent, participants were more likely to remember leg problems, if they were present, in the mother (64.8%) than the father (13.9%). This was a little less likely in the Middle and Far East, but in this region men were proportionally more numerous. Personal history of venous thrombosis concerned 8.3% of participants. Subjects were spending a mean of 6.6+3.1 hours a day in a standing position, and 67.8% did not exercise regularly.

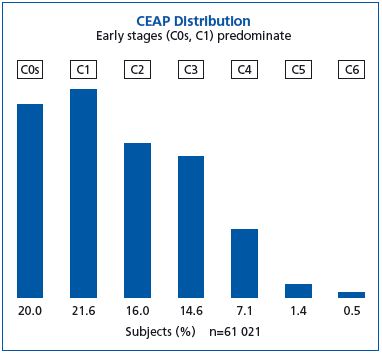

The distribution of the study population as a function of CEAP class is shown in Figure 1. Nearly 58% of subjects were between C0s and C2, stages of CVD that can be considered as early, while nearly 24% were at the stage of chronic venous insufficiency (C3-C6). The prevalence of ulcers, healed and active (2.1%), is in agreement with published data. A total of 61.2% of subjects were at stages C1-C6.

Figure 1. CEAP distribution in the subjects screened in the VEIN

CONSULT Program

A high proportion of subjects complained of leg heaviness (75.4%) and pain (67.3%); a sensation of swelling (54.8%) and night cramp (42.6%) were also common. The rank order of these symptoms varied from one country to another.

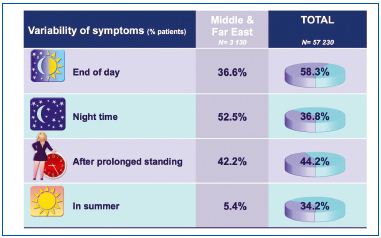

To be ascribed to CVD, symptoms had to vary with the time of day, temperature, and position. Figure 2 shows that CVD symptoms were usually most intense at the end of the day (58.3%) and after prolonged standing (44.2%), and less intense during the night (36.8%). Summer is associated with the appearance of symptoms in countries where the seasons are well defined (34.2%), namely in Europe.

In the Middle and Far East, summer had less climatic variation and this question remained largely unanswered (5.4%). In addition, in this region, symptoms were more likely to be felt with greater intensity during the night (52.5%) than at the end of the day (36.6%).

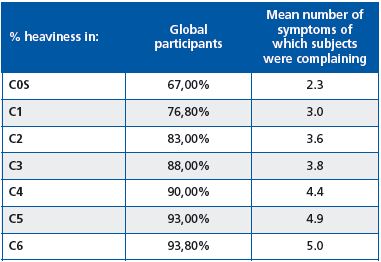

The proportion of patients complaining of symptoms increased with disease severity in accordance with the CEAP classification. Similarly, the mean number of symptoms per patient also increased with disease severity (Table I). This tendency was observed in all countries.

Figure 2. Variability of symptoms according to time, temperature,

and position.

Table I. Percentage of participants with heaviness, and mean

number of symptoms reported according to CEAP classification.

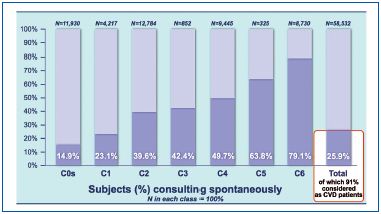

A total of 25.9% of participants consulted a practitioner spontaneously because of leg problems, of which 2% were at stage C0s. If we consider that 61% were assigned stages C1-C6, this means that nearly 40% of C1-C6 patients would not have been detected without VEIN CONSULT Program. As shown in Figure 3, the more advanced the severity of CVD, the more likely patients were to consult spontaneously. It is when the disease worsens (especially from stage C5) that the majority of patients decide to consult a general practitioner (GP).

On the other hand, GPs do not consider patients as having CVD before they present with a sign. Underestimation of CVD by GPs is especially clear at the C0S stage (27% of C0s patients were considered to have CVD), and to a lesser extent at C1 (82%), but is recognized more from stage C2 (92% to 100% of patients considered to have CVD). C0s patients are generally not included in the CVD category (except in France where 1 in 3 patients in this category are considered to have CVD).

Figure 3. Percentage of subjects consulting spontaneously because

of leg problems according to the CEAP classification.

When asked “Do you presently have spider veins, varicose veins, ankle swelling, or ankle ulcer,” 52.8% of patients answered that they had one or several of these signs, but when examined by GPs, 61.2% presented with such signs. CVD seems to be underestimated by patients themselves.

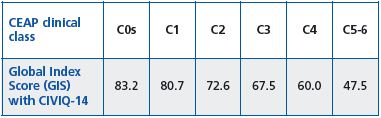

Only patients considered by GPs as having CVD completed the questionnaire about costs and impact on the quality of life. CIVIQ-14 was used to assess the quality of life of patients using the Global Index Score (GIS). A GIS=100 means a very good quality of life and GIS=0 a very bad quality of life.

Among the 25 436 patients who replied to the questionnaire, more than 12%, that is to say more than 3000 patients, had already undergone surgical treatment or sclerotherapy. Nearly 6% of patients had been hospitalized and 3.7% had changed their professional activities because of venous leg problems. Loss of work days was reported in 15% of CVD patients. Number of lost work days did not exceed 1 week for most (45.2%), while 30% of them lost more (18%>1 week and 12%>1 month). Quality-of-life scores decreased with higher frequency of lost work days (from 68.40±19.50 for 1 time to 43.04±22.32 for >3 times) and with duration of the absence from work (from 77.25±18.84 for <1 week to 56.97±22.19 for >1 month).

As CVD increases in severity, GIS scores range from 80.71±16.15 in patients with telangiectasias to 44.17±23.51 in those with an ulcer (Table II), and with the presence of a symptom (84.77±15.96 in patients without pain versus 66.86±19.80 in those with pain).

Table II. Assessment of Global Index Score with CIVIQ-14

according to CEAP classes

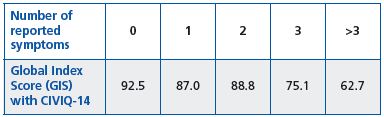

Whatever the symptom concerned, the quality of life score was significantly better in the absence of symptoms. The more symptoms a patient had, the more quality of life deteriorated (Table III).

Table III. Assessment of Global Index Score with CIVIQ-14

according to the number of reported symptoms.

This international epidemiological survey provides a snapshot of CVD in adults consulting primary care physicians. This is the first survey that has used the same questionnaire and the same CEAP classification whatever the country involved. Patients consulting spontaneously for leg problems (>25% of the study population) seem to be numerous. It appears they sought medical advice from stage C2 (varicose veins), but not much before. With 61.2% of participants at stages C1-C6, the prevalence of CVD in the study population was very high. VEIN CONSULT Program data are in line with previous surveys.3,9-15 Prevalence varied with area, age, and sex. It should be emphasized that CVD was present worldwide and not only in the western world. Subjects complaining of symptoms were numerous. The questionnaire focused on symptoms first before examination of legs, which might have introduced a bias. The VEIN CONSULT Program is the first survey that has distinguished between C0a (healthy people) and C0s (complaining of symptoms without CVD signs) participants. Of particular interest is the high prevalence of the C0s population (20%) particularly in the Middle East where participants were younger than in the whole sample. Considering the high prevalence of the C0s population (20%) particularly in Middle East, more than 50 % complaining about symptoms during night time, it is debatable, if these complaints are really caused by venous problems, justifying the description C0 or to other, non-specific ailments. (The CEAP classification is by definition a classification of chronic venous disorders which should exclude non- venous pathologies. To ascertain whether C0s patients, who do not present with a detectable venous pathophysiology (Pn) have a venous disorder, medical questioning should delve deeper into the symptoms since we know that many subjective leg symptoms (eg, night cramps) can have other causes as well. Complaints for leg problems may occur whatever the country and culture, even if symptoms increase with the severity of CVD. The VEIN CONSULT Program confirms that CVD is a costly disease that may cause considerable suffering to patients.

Despite these facts, CVD remains underdiagnosed, as confirmed in the VEIN CONSULT Program, which detected nearly 40% of C1-C6 patients. The reasons for this are multiple16 and include inadequate graduate and postgraduate training, diffuse nature of the disease presentation, intervention of numerous specialities, lack of understanding of preventability and treatment, lack of focused interest by many practitioners. The role of GPs in the diagnosis of CVD is critical as early intervention may prevent progression of this chronic disease, and treatment of early skin changes increases the chances of preserving the tissues of the lower leg, and referral of patients to a specialist is crucial in obtaining venous testing, particularly at advanced disease stages.

REFERENCES

1. Langer RD, Ho E, Denenberg JO, et al. Relationships between symptoms and venous disease: the San Diego population study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1420-1424.

2. Jantet G. Chronic venous insufficiency: worldwide results of the RELIEF study. Angiology. 2002;53:245-256.

3. Rabe E, Pannier-Fischer F, et al. Bonner Venenstudie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Phlebologie. Phlebologie. 2003;32:1- 14

4. International Task Force. The management of chronic venous disorders of the leg: an evidence-based report of an international task force. Phlebology. 1999;14(suppl 1):23.

5. Robertson L, Evans C, Fowkes FGR. Epidemiology of chronic venous disease. Phlebology. 2008;23:103-111.

6. Nicolaides AN, Allegra C, Bergan J, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs: guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int Angiol. 2008;27:1-59.

7. Lyseng-Williamson KA, Perry CM. Micronised purified flavonoid fraction. A review of its use in chronic venous insufficiency, venous ulcers and haemorrhoids. Drugs. 2003;63:71-100.

8. Andreozzi GM, Signorelli S, Di Pino L, et al. Varicose symptoms without varicose veins: the hypotonic phlebopathy, epidemiology and pathophysiology. The Acireale project. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2000;48:277-285.

9. Chiesa R, Marone EM, Limoni C, et al. Chronic venous insufficiency in Italy: the 24-cities cohort study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:422-429.

10. Criqui MH, Jamosmos M, Fronek A, et al. Chronic venous disease in an ethnically diverse population: the San Diego Population Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:448-456.

11. Evans C, Fowkes F, Ruckley C, et al. Prevalence of varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency in men and women in the general population: Edinburgh vein Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:149-153.

12. Jawien A, Grzela T, Ochwat A. Prevalence of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) in men and women in Poland: multicenter cross-sectional study in 40 095 patients. Phlebology. 2003;18:110-122

13. Zahariev T, Anastassov V, Girov K, et al. Prevalence of primary chronic venous disease: the Bulgarian experience. Int Angiol. 2009;28:303- 310.

14. Carpentier PH, Maricq HR, Biro C, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical patterns of chronic venous disorders of lower limbs: A population-based study in France, J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:650- 659.

15. Scuderi A, Raskin B, Assal F, et al. The incidence of venous disease in Brazil based on the CEAP classification. Int Angiol. 2002; 21:316-21

16. Henke P, Pacific Vascular Symposium 6 Faculty. J Vasc Surg. 2010; 52(5 Suppl):1S-2S.