An update on operative treatments of primary superficial vein incompetence: part 2.

of primary superficial vein

incompetence: part I.

Unité de Pathologie Vasculaire

Jean Kunlin

Chassieu, France

Abstract

In part 2 of “An update on operative treatment of primary superficial vein incompetence,” all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published since 1990 on operative treatments of varicose veins were collected and the references were gathered in tables according to either the procedure used or the patient’s clinical status. Case series and meta-analyses were taken into account in this review when RCTs were not available. For more details regarding clinical or instrumental outcomes of the studies described, please go to www.phlebolymphology.org. In the second part of this article, the indications for operative treatment of varicose veins will be discussed. These indications are not specific, as many factors must be taken into account and, unfortunately, in practice it is not always based on evidence. Finally, the recently published international recommendations about the use of the various procedures for varicose vein ablation will be reviewed.

Outcomes after operative treatment

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are very good tools for comparing the results of the various operative treatments for varicose veins. Yet, before drawing definitive conclusions on any of these procedures, an accurate publication analysis is mandatory as RCTs often contain hard-to-identify bias. For example, the short-term results of a procedure greatly depend on the type of anesthesia performed during varicose vein ablation (local tumescent anesthesia or general anesthesia).1 In the absence of RCTs for evaluating a procedure, case series are considered even though they provide a weaker level of evidence. Well-designed meta-analyses can provide valuable information for clinicians. By combining RCTs, meta-analyses increase the sample size, and thus, the power to study the results of a given procedure. Study outcomes are usually divided into the following 3 categories: (i) postoperative outcomes (3 years for RCTs and >5 years for case series. Nevertheless, this review’s outcome analysis has been divided into two parts: (i) postoperative and mid-term outcomes and (ii) long-term outcomes.

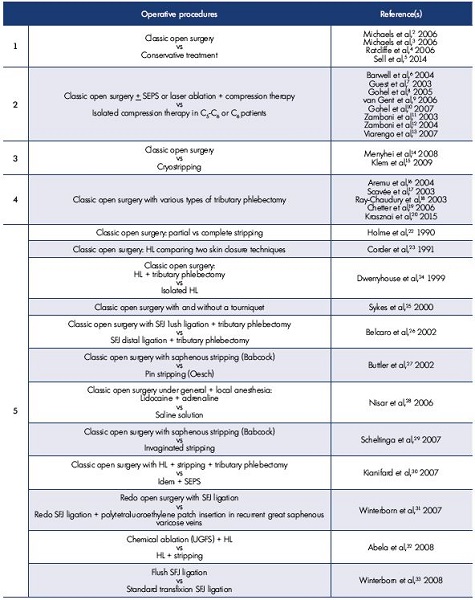

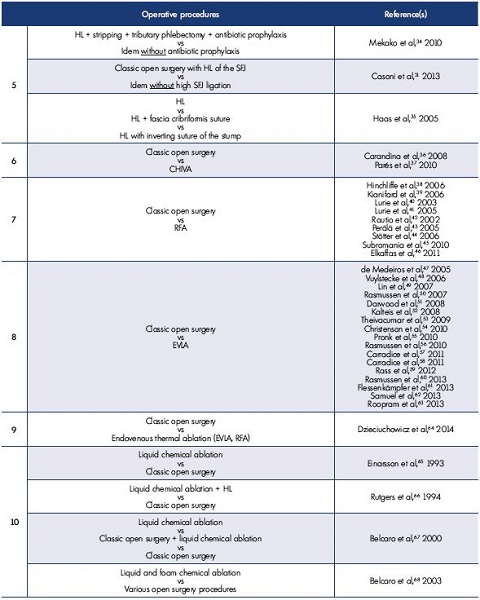

Open surgery

Classic open surgery has been compared with conservative treatment both in C2 and C5-C6 patients (Tables I.1 and I.2).2-13 In addition, classic open surgery has been compared with open surgery variants (Tables I.3 and I.4), such as cryostripping14,15 and tributary-powered phlebectomy16-20– techniques that are only rarely used in current practice. Some RCTs (Table I.5)22-35 provide interesting information on how classical stripping influences nerve damage,22,25,29 the short- and long-term outcomes according to the procedure used,24,30,33 the results following saphenofemoral junction ablation and ligation21,26,35 or associated perforator ablation.30 The RCTs comparing classic open surgery with other ablative procedures are more interesting and are shown in Table I.6 to I.15.36-86 Additionally, the CHIVA method (Cure Hémodynamique de l’Insuffisance Veineuse en Ambulatoire [conservative ambulatory hemodynamic management of varicose veins]) is performed under local anesthesia when other open surgery techniques need spinal or general anesthesia, and as a result, CHIVA shortens the length of the hospital stay (Table I.6).36,37

All RCTs that compared the short-term results of classic open surgery with radiofrequency ablation (RFA), endovenous laser ablation (EVLA), endovenous steam ablation,81 endovenous microwave ablation, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS), and high ligation with tributary phlebectomy concluded that both endovenous procedures and high ligation with tributary phlebectomy are less painful than classic open surgery and these procedures shorten the time required before returning to normal activity. Sensory impairment and ecchymosis are less severe with endovenous microwave ablation than open surgery, even though endovenous microwave ablation causes skin burns, 10% of which are related to slow probe withdrawal or using energy that is too high (Table I.14).82 However, when modern open surgery is performed under local anesthesia (unfortunately by very few teams), it is as effective postoperatively as any endovenous procedure.

Endovenous procedures

Endovenous procedures have been widely studied and compared with open surgery and other endovenous procedures.

Thermal ablation

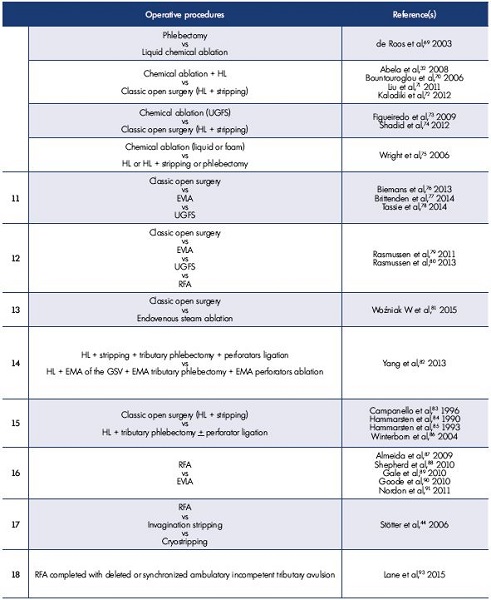

Radiofrequency ablation. RFA has been compared with open surgery, cryostripping, invagination stripping, EVLA, and UGFS (Table I.7, I.12, I.16, and I.17).38-46,79,80,87-91 Studies of EVLA using bare fibers vs RFA favored the latter since it is less painful and results in less ecchymosis. However, it is now acknowledged that radial fibers, which are currently used, provide better postoperative results than bare fibers.92 No differences in efficacy and undesirable effects were observed between RFA and UGFS in a 4-arm study.79,80 At a 1-year follow-up, redo operations were less frequent after RFA compared with deleted or synchronized ambulatory incompetent tributary avulsion (Table I.18).93

Endovenous laser ablation. Treating varicose veins with EVLA is a safe procedure in patients with active ulcers. Ulcers healed faster after EVLA than in patients undergoing compression therapy alone and no ulcer recurrence occurred during a 1-year period posttreament.13 EVLA has been compared with open surgery, cryostripping, invagination stripping, EVLA has been compared with open surgery (Table I.8)47-63, with open surgery and UGFS (Table I.11)76-78, in a 4-arm RCT including open surgery, EVLA, RFA, UGFS (Table I.12)79-80, with invagination stripping (Table I.16)87-91, with steam ablation (Table I.19)100, and with cryostripping (Table I.29).94-96 All procedures were similarly effective in patients with varicose veins94,95 and EVLA had a similar, but slightly higher cost.96

When comparing UGFS and EVLA (Table I.11 and I.25),76-78,97-99 no differences at 3 months97,98 were observed for clinical results or vein obliteration, but UGFS outperformed EVLA in cost, treatment duration, postoperative pain reduction, and recovery. At 15 months,99 there were no differences in clinical results, but vein occlusion was higher with EVLA. At a 1-year follow-up, Biemans et al found no difference between the EVLA and UGFS in complications and clinical results, but UGFS resulted in lower occlusion rates.76 Brittenden et al showed similar clinical efficacy between UGFS and EVLA, but EVLA had fewer complications and UGFS had lower ablation rates at both 6 weeks and 6 months posttreatment.77 Tassie et al showed that EVLA has the highest probability of being cost-effective compared with classic open surgery and UGFS.78

The 1-year treatment success of high-dose EVLA was not inferior to that of endovenous steam ablation. Several secondary outcomes (eg, painful legs, patients’ satisfaction, duration of analgesia, and limitations in daily life) were in favor of endovenous steam ablation (P<0.001).100

Data from ten RCTs on EVLA variants (Table I.20)92,101-111 show that: (i) below-knee EVLA was not associated with saphenous nerve injury104; (ii) lower postoperative pain and better Venous Clinical Severity Scores (VCSS) were obtained with radial fibers compared with bare fibers92 or tulip fibers109; (iii) cold tumescent anesthesia had fewer side effects and a reduction in analgesic intake than warm tumescent anesthesia106,107; and (iv) symptom intensity was lower and quality of life better when compression was applied for 2 to 7 days posttreatment.110

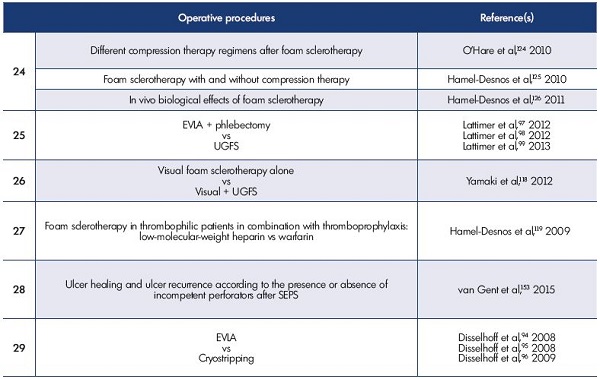

Table I. Randomized controlled trials, case series, and meta-analyses comparing operative procedures for the treatment of primary

superficial vein incompetence.

For more information on the trials, please go to www.phlebolymphology.org.

Abbreviations: CHIVA, Cure Hémodynamique de l’Insuffisance Veineuse en Ambulatoire (Conservative ambulatory HemodynamIc

management of VAricose veins); EMA, endovenous microwave ablation; EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; GSV, great saphenous

vein; HL, high ligation; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SEPS, subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery; SFJ, saphenofemoral junction;

UGFS, ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy.

Chemical ablation

Sclerotherapy. Postoperative, short-term, and mid-term results are difficult to compare because many different protocols and outcome criteria were used (Tables I.10 to I.12).65-80 RCTs on variants of sclerotherapy provide some data on postoperative course and short- or mid-term outcomes. Foam sclerotherapy provides better results than liquid sclerotherapy (Table I.22),113-117 and occlusion rates are similar when using either a 1% or 3% polidocanol foam solution (Table I.24).124-126 The use of postoperative compression does not influence the percentage of patients with side effects after UGFS (Table I.25).97-99

Glue. No RCTs evaluating glue vs other procedures have been conducted, but a case series has reported good results at a 2-year follow-up–occlusion rates were 92% and a significant improvement in VCSS was observed.127

Mechanochemical ablation

There are no RCTs for Clarivein_, but case series are available.128-130 At a 6-month follow-up, the occlusion rate was 96% and the VCSS improved in a series of patients presenting with saphenous vein varices.128 In the case series by Boersma et al on patients who underwent short saphenous vein ablation, the occlusion rate at 1 year was 94% and the VCSS improved.130

Clinical parameters

PREVAIT

The term PREsence of Varices After operatIve Treatment (PREVAIT) was adopted in the VEIN-TERM transatlantic interdisciplinary consensus document.131 PREVAIT is a frustrating problem for both the patients with varicose veins and the physicians who treat these varicose veins. Recurrent Varices After Surgery (REVAS) have been previously compared with classic open surgery.132

Severity scores

The Venous Clinical Score (VCSS), Venous Segmental Disease Score (VSDS), and Aberdeen Varicose Vein Severity Score (AVVSS)–are used in the literature to assess treatment success rates. VCSS is a very good tool for evaluating the treatment of complicated varices, but it is less informative for uncomplicated C2 patients.133,134

Generic and specific health-related quality of life questionnaires

Many health-related quality of life questionnaires have been used, including AVVQ, the Chronic Venous Insufficiency Quality of Life Questionnaire (CIVIQ), the Specific Quality of Life and Outcome Response-Venous (SQOR-V), and the results have been compared with anatomic, hemodynamic, and clinical outcomes before and after operative treatment.135 Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) are new and very promising tools.136

Instrumental investigation measurements

These measurements rely on occlusion rates and hemodynamic function. It has been clearly identified that the correlation between clinical and investigational parameters is far from perfect.

Information provided by RCTs

Open surgery vs high ligation and tributary phlebectomy

These procedures were assessed in 2 RCTs with 4, 5, and 11 years of follow-up24,83-86 and there were no differences in clinical outcomes. More redo surgery was performed in the group with high ligation and tributary phlebectomy, but preoperative and postoperative investigations were outdated in both groups.

Open surgery vs CHIVA

CHIVA was compared with classic open surgery in 2 RCTs with 5 and 10 years of follow-up (Table I.6).36,37 Both RCTs favor CHIVA in terms of PREVAIT reduction, but bias was identified to weaken the authors’ conclusions.

Open surgery vs radiofrequency ablation

Only one RCT comparing long-term outcomes (3-year) of open surgery with RFA is available and there was no difference in clinical results between the two groups,150 but the Closure® catheter used was older and less efficient that the Closure FAST® catheter.

Open surgery vs EVLA

At a 5-year follow-up, a RCT comparing EVLA with open surgery found no difference between the 2 groups in persistent reflux, PREVAIT, redo treatment, VCSS, and generic and specific health-related quality of life scores. In this trial, open surgery was minimally invasive and the EVLA procedure used a bare fiber with a 980-nm diode laser and a stepwise laser withdrawal.60

Sclerotherapy vs various open surgery procedures

Belcaro et al reported two series with long-term follow-up data, but no conclusive results were obtained.67,68 The RCT comparing UGFS complemented by high ligation with open surgery at a 3- to 5-year follow-up was more informative, showing that the treatment was equally effective in both groups, which was demonstrated by improvements in the VCSS, VSDS, and the generic health-related quality of life scores. At 5 years posttreatment, the AVVQ was significantly better in the open surgery group.72

Information provided by case series

Open surgery

The most documented outcomes are provided by classic open surgery, but most studies are retrospective. In a 34-year follow-up study, varicose veins were present in 77% of the lower limbs examined and most were symptomatic–58% were painful, 83% had a tired feeling, and 93% showed a reappearance of edema.137 Two prospective studies concerning classic open surgery are available with a 5-year follow-up.138,139 In both studies, patients were preoperatively investigated with duplex scanning and treated by high ligation, saphenous trunk stripping, and stab avulsion. In the Kostas et al series, 28 out of 100 patients had PREVAIT after 5 years, where the recurrent varices mainly resulted from neovascularization (8/28, 29%), new varicose veins as a consequence of disease progression (7/28, 25%), residual veins due to tactical errors (eg, failure to strip the great saphenous vein) (3/28, 11%), and complex patterns (10/28, 36%).139

In the van Rij series, 127 limbs (CEAP class C2-C6) were evaluated postoperatively by clinical examination, duplex scanning, and air plethysmography. At the clinical evaluation, recurrence of varicose veins was progressive from 3 months (13.7%) to 5 years (51.7%). In line with clinical changes, a progressive deterioration in venous function was measured by air plethysmography and reflux recurrence was assessed by duplex scanning.138 These two studies showed that recurrence of varicose veins after surgery is common, even in highly skilled centers. Even if the clinical condition of most affected limbs after surgery improved compared with before surgery, progression of the disease and neovascularization are responsible for more than half of the recurrences. Rigorous evaluation of patients and assiduous surgical techniques might reduce the recurrence resulting from technical and tactical failures.

Other procedures

A 5-year follow-up of a large series of patients treated with RFA using a Closure plus catheter showed that vein occlusion and absence of reflux were present in 87.2% and 83.8% of patients, respectively. Symptoms, including pain, fatigue, and edema, significantly improved compared with the preoperative status. The rate of PREVAIT progressed from 6 months (7.7%) to 5 years (27.4%).140 Currently, no longterm results are available for Glue and Clarivein®

Information provided by meta-analyses

Since 2009, six meta-analyses on operative treatment of primary varicose veins by open surgery, RFA, EVLA, and UGFS were identified–all produced similar conclusions.141-146

Final remarks concerning outcomes after operative treatment

The immediate postoperative course, including side effects, recovery time, and convalescence, is better in all other procedures compared with classic open surgery, but this point is questioned if modern and minimally aggressive open surgery is used. No differences in recurrence between classic open surgery compared with RFA and EVLA are present at the mid- or long-term follow-up. PREVAIT is more frequent after UGFS compared with other mentioned procedures, but PREVAIT can be easily and effectively treated with redo UGFS.

Operative treatment indications

In patients with primary superficial reflux who are classified as C2, indications for operative treatment rely on patient complaints, such as symptoms and cosmetics, and on the extent and size of the varices. For patients in the C3 to C6 classes, operative treatment must be considered in all cases, except for the usual contraindications. However, in all clinical classes, nonvenous causes must be identified because venous symptoms are not pathognomonic and some signs, including edema and ulcers may be due to other etiologies. In the presence of axial deep primary reflux combined with primary varices, varicose veins must be treated first. However, we know that, in about half of the patients, axial deep primary reflux is not corrected by varicose vein ablation147 and its persistence is responsible for varices recurrence.148,149

When incompetent perforators are associated with primary varices, do they need to be treated in the same session? As no RCTs have compared the outcomes after varicose vein ablation with perforator ablation + varices ablation, no evidence-based information is available. Nevertheless, we know that, in half of these patients, incompetent perforators are no longer identified after varices ablation.* To summarize, perforator ablation can be reserved for patients with persistent incompetent perforator vessels, abnormal hemodynamic parameters, or continued symptoms and/or signs (C4b-C6) after superficial ablative surgery.152 Nevertheless, one RCT favors treating perforators in C6 patients to prevent ulcer recurrence (Table I.28).153

PREVAIT represents a particular situation in terms of indication.154 Managing patients with PREVAIT varies according to the clinical situation. Patients attending a routine follow-up, who are either asymptomatic or symptomatic, and not complaining of recurrences are managed differently than symptomatic patients who are complaining of cosmetic problems and presenting with complicated varices (C3-C6).150 A consensus document agrees that UGFS is the first-line treatment in almost all cases, except in patients presenting with varicose veins of the lower limbs that are fed by pelvic refluxive veins. The European guidelines for sclerotherapy assigned a Grade 1B to this procedure.156 In the absence of RCTs, this recommendation is based on case series.157,158

* Except in presence of associated axial deep reflux.150-152

In practice, the choice of the procedure is frequently not made on evidence-based data, but on other factors, such as: (i) personal mastery of the different techniques– practitioners will favor the procedures they have mastered; (ii) coverage/reimbursement by the health services/ health insurance, which varies from country to country; (iii) the patient’s choice, which is influenced by possible postoperative problems, recovery time, time off work, the procedure that provides the easiest control of recurrences, and information from friends, literature, or the internet.

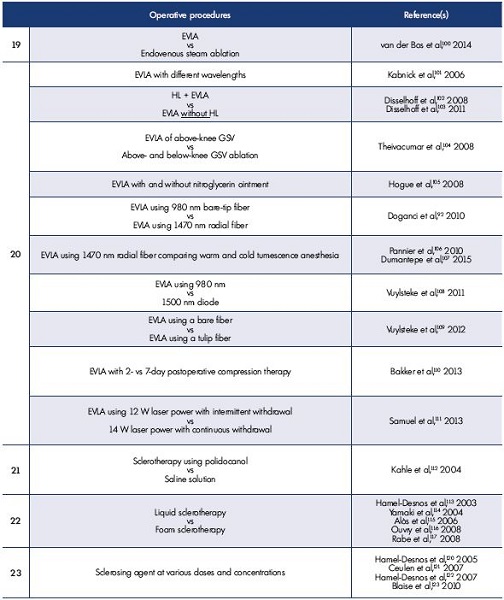

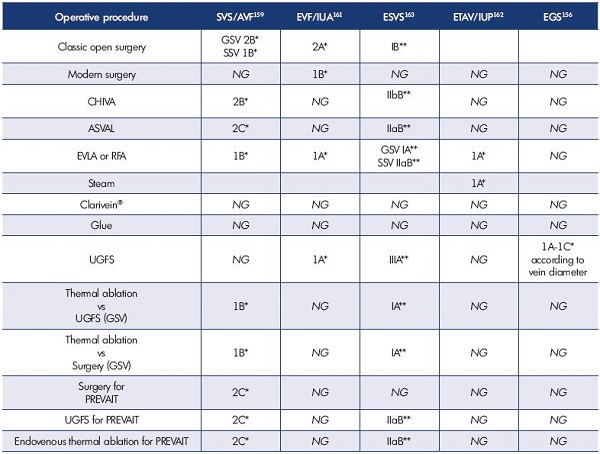

Table II. Recommendations for operative procedures for the treatment of superficial refluxing veins from the recent guidelines.

*Guyatt’s grading164

**Grading system of the European Society of Cardiology165

Abbreviations: ASVAL, Ablation Selective des Varices sous Anesthésie Locale (Ambulatory Selective Vein Ablation under Local

anesthesia); AVF, American Venous Forum; CHIVA, Cure Hémodynamique de l’Insuffisance Veineuse en Ambulatoire (Conservative

ambulatory HemodynamIc management of VAricose veins); EGS, European Guide for Sclerotherapy; EVLA, endovenous laser

ablation; ESVS, European Society of Vascular Surgery; ETAV, Endovenous Thermal Ablation for Varicose Vein Disease; EVF, European

Venous Forum; GSV, great saphenous vein; IUA, International Union of Angiology; IUP, International Union of Phlebology; NG, not

graded; PREVAIT, PREsence of VArices after operatIve Treatment; SSV, small saphenous vein; SVS, Society of Vascular Surgery; UGFS,

ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy.

Guidelines

Recommendations from five guidelines are summarized in Table II. The guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery/ American Venous Forum (SVS/AVF) were published in 2011.159 Most recommendations remain valid, but are not fully applicable in Europe. The SVS/AVF guidelines were analyzed by a European team.160 In 2013, the European Guide for Sclerotherapy was made available, giving much information on sclerotherapy, including practical information.156 In 2014, the European Venous Forum (EVF) and the International Union of Angiology (IUA) published a guidelines document on the management of chronic venous disorders.161 The International guidelines on endovenous thermal ablation were published in 2015. This consensus document also provides many technical details.162 The same year, the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) endorsed guidelines on the management of chronic venous disease.163

Most of these guidelines used the Guyatt grading scheme, which classifies recommendations as strong (grade 1) or weak (grade 2), according to the balance among benefits, risks, burdens, cost, and the degree of confidence in the estimates of benefits, risks, and burdens. It classifies quality of evidence as high (grade A), moderate (grade B), or low (grade C) according to factors, such as study design, consistency of the results, and directness of the evidence.164 Only the ESVS guidelines used the European Society of Cardiology’s grading system. For each recommendation, the letter A, B, or C marks the level of current evidence. Weighing the level of evidence and expert opinion, every recommendation is subsequently marked as either class I, IIa, IIb, or III. The lower the class number, the more proven the efficacy and safety of a certain procedure.165

In 2013, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published a document on varicose veins of the leg,166 where the recommendations for people with confirmed varicose veins and truncal reflux were as follows:

• First, offer endothermal ablation (RFA for varicose veins [NICE interventional procedure guidance 8]167 and EVLA for the long saphenous vein [NICE interventional procedure guidance 52]168).

• If endothermal ablation is unsuitable, offer UGFS (see UGFS for varicose veins [NICE interventional procedure guidance 440]169).

• If UGFS is unsuitable, offer surgery.

• If incompetent varicose tributaries are to be treated, consider treating them at the same time.166

Conclusions

Operative treatment of primary varicose veins is currently performed using minimally invasive procedures, excluding spinal or general anesthesia. The problem is that the development of new procedures or devices is so rapid that when long-term outcomes are available, particularly for RCTs, the technique or material evaluated is frequently no longer used. Postoperative quality of life has improved, complications are far less frequent, and sick leave is shorter. The long-term frequency of PREVAIT is approximately the same for all techniques used, as long as the initial procedure has been correctly executed. To minimize the severity of PREVAIT, it is crucial to have regular patient follow-up and use ultrasound investigation to manage possible varices recurrence.

REFERENCES

1. Thakur B, Shalhoub J, Hill AM, Gohel MS, Davies AH. Heterogeneity of reporting standards in randomised clinical trials of endovenous interventions for varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40:528-533.

2. Michaels JA, Brazier JE, Campbell WB, MacIntyre JB, Palfreyman SJ, Ratcliffe J. Randomized clinical trial comparing surgery with conservative treatment for uncomplicated varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2006;93:175-181.

3. Michaels JA, Campbell WB, Brazier JE, et al. Randomised clinical trial, observational study and assessment of cost-effectiveness of the treatment of varicose veins (REACTIV trial). Health Technol Assess. 2006;10:1-196.

4. Ratcliffe J, Brazier JE, Campbell WB, Palfreyman SJ, MacIntyre JB, Michaels JA. Cost effectiveness analysis of surgery versus conservative treatment for uncomplicated varicose veins in a randomized control trial. Br J Surg. 2006;93:182-186.

5. Sell H, Vikatamaa P, Albäck A, et al. Compression therapy versus surgery in the treatment of patients with varicose veins: a RCT. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;47:670-677.

6. Barwell JR, Davies CE, Deacon J, et al. Comparison of surgery and compression with compression alone in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1854-1859.

7. Guest M, Smith JJ, Tripuraneni G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of varicose vein surgery with compression versus compression alone for the treatment of venous ulceration. Phlebology. 2003;18:130-136.

8. Gohel MS, Barwell JR, Earnshaw JJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial of compression plus surgery versus compression alone in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR study)— haemodynamic and anatomical changes. Br J Surg. 2005;92:291-297.

9. van Gent WB, Hop WC, van Praag MC, Mackaay AJ, de Boer EM, Wittens CH. Conservative versus surgical treatment of venous leg ulcers: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:563-571.

10. Gohel MS, Barwell JR, Taylor M, et al. Long term results of compression therapy versus compression plus surgery in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR): a randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:83.

11. Zamboni P, Cisno C, Marchetti F, et al. Minimally invasive surgical management of primary venous ulcers vs. compression treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;25:313-318.

12. Zamboni P, Cisno C, Marchetti F, et al. Haemodynamic CHIVA correction surgery versus compression for primary venous ulcers: first year results. Phlebology. 2004;19:28-34.

13. Viarengo LM, Potério-Filhio J, Potério GM, Menezes FH, Meirelles GV. Endovenous laser treatment for varicose veins in patients with active ulcers: measurement of intravenous and perivenous temperatures during the procedure. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1234-1242.

14. Menyhei G, Gyevnàr Z, Aratá E, Kelemen O, Kollár L. Conventional stripping versus cryostripping: a prospective randomised trial to compare improvement in quality of life and complications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:218-223.

15. Klem TM, Schnater JM, Schütte PR, Hop W, van der Ham AC, Wittens CH. A randomized trial of cryostripping versus conventional stripping of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:403-409.

16. Aremu M, Mahendran B, Butcher W, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial: conventional versus powered phlebectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:88- 94.

17. Scavée V, Lesceu O, Theys S, Jamart J, Louagie Y, Schoevaerdts JC. Hook phlebectomy versus transilluminated powered phlebectomy for varicose veins surgery: early results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;25:473-475.

18. Ray-Chaudury S, Huq Z, Souter R, McWhinnie D. A randomized controlled trial comparing transilluminated powered phlebectomy with hook avulsions. An adjunct to day surgery? J One-Day Surg. 2003;13:24-27.

19. Chetter IC, Mylankal KJ, Hughes H, Fitridge R. Randomized clinical trial comparing multiple stab incision phlebectomy and transilluminated powered phlebectomy for varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2006;93:169-174.

20. Krasznai AG, Sigterman TA, Willems CE, et al. Prospective study of a single treatment strategy for local tumescent anesthesia in Muller phlebectomy. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:586-593.

21. Casoni P, Lefebvre-Vilardebo M, Villa F, Corona P. Great saphenous vein surgery without high ligation of the saphenofemoral junction. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:173-178.

22. Holme JB, Skajaa K, Holme K. Incidence of lesions of the saphenous nerve after partial or complete stripping of the long saphenous vein. Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:145-148.

23. Corder AP, Schache DJ, Farquharson SM, Tristram S. Wound infection following high saphenous ligation: a trial comparing two skin closure techniques: subcuticular polyglycolic acid and interrupted monofilament nylon mattress sutures. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1991;36:100-102.

24. Dwerryhouse S, Davies B, Harradine K, Earnshaw JJ. Stripping the long saphenous vein reduces the rate of reoperation for recurrent varicose veins: five-year results of a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 1999;29:589-592.

25. Sykes TC, Brookes P, Hickey NC. A prospective randomised trial of tourniquet in varicose vein surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82:280-282.

26. Belcaro G, Nicolaides AN, Cesarone NM, et al. Flush ligation of the saphenofemoral junction vs simple distal ligation, 10 year, follow-up. The safe study. Angéiologie. 2002;54:19-23.

27. Butler CM, Scurr JH, Coleridge Smith PD. Prospective randomized trial comparing conventional (Babcock) stripping with inverting (Pin) stripping of the long saphenous vein. Phebology. 2002;17:59-63.

28. Nisar A, Shabbir J, Tubassam MA, et al. Local anaesthesic flush reduces postoperative pain and haematoma formation after great saphenous vein stripping–a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:325-331.

29. Scheltinga MR, Wijburg ER, Keulers BJ, de Kroon KE. Conventional versus invaginated stripping of the great saphenous vein: a randomized doubleblind, controlled clinical trial. World J Surg. 2007;31:2236-2242.

30. Kianifard B, Holdstock J, Allen C, Smith C, Price B, Whiteley MS. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of adding subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery to standard great saphenous vein stripping. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1075- 1080.

31. Winterborn RJ, Earnshaw JJ. Randomized trial of polytetrafluoroethylene patch for recurrent great saphenous varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:367-373.

32. Abela R, Liamis A, Prionidis I, et al. Reverse foam sclerotherapy of the great saphenous vein and sapheno-femoral ligation compared to standard and invagination stripping: a prospective clinical series. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:485-490.

33. Winterborn RJ, Foy C, Heather H, Earnshaw JJ. Randomized trial of flush saphenofemoral ligation for primary great saphenous varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:477-484.

34. Mekako AI, Chetter IC, Coughlin PA, Hatfield J, McCollum PT; Hull Antibiotic pRophylaxis in varicose Vein Surgery Trialists (HARVEST). Randomized clinical trial of co-amoxiclav versus no antibiotic prophylaxis in varicose vein surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97:29-36.

35. Haas E, Burkhardt T, Maile N. Rezidivhäufigkeit durch neoangiogenese nach modifizierter krossektomie prospektiv-randomisierte, farbduplex-kontrollierte studie. Phlebologie. 2005;34:101-104.

36. Carandina S, Mari C, De Palma M, et al. Varicose vein stripping vs haemodynamic correction (CHIVA): a long term randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:230-237.

37. Parés JO, Juan J, Tellez R, et al. Varicose vein surgery: stripping versus the CHIVA method—a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2010;251:624-631.

38. Hinchliffe RJ, Ubhi J, Beech A, Ellison J, Braithwaite BD. A prospective randomised controlled trial of VNUS closure versus surgery for the treatment of recurrent long saphenous varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:212-218.

39. Kianifard B, Holdstock JM, Whiteley MS. Radiofrequency ablation (VNUS closure) does not cause neo-vascularisation at the groin at one year: results of a case controlled study. Surgeon. 2006;4:71-74.

40. Lurie F, Creton D, Eklof B, et al. Prospective randomized study of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration (closure procedure) versus ligation and stripping in a selected patient population (EVOLVeS Study). J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:207-214.

41. Lurie F, Creton D, Eklof B, et al. Prospective randomized study of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration (closure) versus ligation and vein stripping (EVOLVeS): two-year follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29:67- 73.

42. Rautio T, Ohinmaa A, Perälä J, et al. Endovenous obliteration versus conventional stripping operation in the treatment of primary varicose veins: a randomized controlled trial with comparison of the costs. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:958-965.

43. Perälä J, Rautio T, Biancari F, et al. Radiofrequency endovenous obliteration versus stripping of the long saphenous vein in the management of primary varicose veins: 3-year outcome of a randomized study. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:669-672.

44. Stötter L, Schaaf I, Bockelbrink A. Comparative outcomes of radiofrequency endoluminal ablation, invagination stripping and cryostripping in the treatment of great saphenous vein insufficiency. Phlebology. 2006;21:60-64.

45. Subromania S, Lees T. Radiofrequency ablation vs conventional surgery for varicose veins—a comparison of treatment costs in a randomized trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:104- 111.

46. Elkaffas KH, Elkashef O, ElBaz W. Great saphenous vein radiofrequency ablation versus standard stripping in the management of primary varicose veins–a randomized clinical trial. Angiology. 2011;62:49-54.

47. de Medeiros CA, Luccas GC. Comparison of endovenous treatment with an 810 nm laser versus conventional stripping of the great saphenous vein in patients with primary varicose veins. Dermatol Surg 2005;31:1685-1694.

48. Vuylsteke M, Van den Bussche D, Audenaert EA, Lissens P. Endovenous laser obliteration for the treatment of primary varicose veins. Phlebology. 2006;21:80-87.

49. Lin Y, Ye CS, Huang XL, Ye JL, Yin HH, Wang SM. A random, comparative study on endovenous laser therapy and saphenous veins stripping for the treatment of great saphenous vein incompetence [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;87:3043-3046.

50. Rasmussen LH, Bjoern L, Lawaetz M, Blemings A, Lawaetz B, Eklof B. Randomized trial comparing endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein with high ligation and stripping in patients with varicose veins: short-term results. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:308-315.

51. Darwood RJ, Theivacumar N, Dellagrammaticas D, Mavor AI, Gough MJ. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation with surgery for the treatment of primary great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2008;95:294-301.

52. Kalteis M, Berger I, Messie-Werndl S, et al. High ligation combined with stripping and endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein: early results of a randomized controlled study. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:822-829.

53. Theivacumar NS, Darwood R, Gough MJ. Neovascularization and recurrence 2 years after varicose vein treatment for sapheno-femoral and great saphenous reflux: a comparison of surgery and endovenous laser ablation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:203-207.

54. Christenson JT, Gueddi S, Gemayel G, Bounameaux H. Prospective randomized trial comparing endovenous laser ablation and surgery for treatment of primary great saphenous varicose veins with a 2-year follow-up. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:1234- 1241.

55. Pronk P, Gauw SA, Mooij MC, et al. Randomised controlled trial comparing sapheno-femoral ligation and stripping of the great saphenous vein with endovenous laser ablation (980 nm) using local tumescent anaesthesia: one year results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40:649-656.

56. Rasmussen LH, Bjoern L, Lawaetz M, Lawaetz B, Blemings A, Eklöf B. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation with stripping of the great saphenous vein: clinical outcome and recurrence after 2 years. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:630-635.

57. Carradice D, Mekako AI, Mazari FA, Samuel N, Hatfield J, Chetter IC. Randomized clinical trial of endovenous laser ablation compared with conventional surgery for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2011;98:501-510.

58. Carradice D, Mekako AI, Mazari FA, Samuel N, Hatfield J, Chetter IC. Clinical and technical outcomes from a randomized clinical trial of endovenous laser ablation compared with conventional surgery for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Sur. 2011;98:1117-1123.

59. Rass K, Frings N, Glowacki P, et al. Comparable effectiveness of endovenous laser ablation and high ligation with stripping of the great saphenous vein: two-year results of a randomized clinical trial (RELACS study). Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:49-58.

60. Rasmussen L, Lawaetz M, Bjoern L, Blemings A, Eklof B. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation and stripping of the great saphenous vein with clinical and duplex outcome after 5 years. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:421-426.

61. Flessenkämpfer I, Hartmann M, Stenger D, Roll S. Endovenous laser ablation with and without high ligation compared with high ligation and stripping in the treatment of great saphenous varicose veins: initial results of a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Phlebology. 2013;28:16-23.

62. Samuel N, Carradice D, Wallace T, Mekako A, Hatfield J, Chetter I. Randomized clinical trial of endovenous laser ablation versus conventional surgery for small saphenous varicose veins. Ann Surg. 2013;257:419-426.

63. Roopram AD, Lind MY, Van Brussel JP, et al. Endovenous laser ablation versus conventional surgery in the treatment of small saphenous vein incompetence. J Vasc Surg: Venous Lym Dis. 2013;1:357- 363.

64. Dzieciuchowicz L, Espinosa G, Páramo JA. Hemostatic activation and inflammatory response after three methods of treatment of great saphenous vein incompetence. Phlebology. 2014;29:154-163.

65. Einarsson E, Eklöf B, Neglén P. Sclerotherapy or surgery as treatment for varicose veins: a prospective randomized study. Phlebology. 1993;8:22-26.

66. Rutgers PH, Kitslaar PJ. Randomized trial of stripping versus high ligation combined with sclerotherapy in the treatment of the incompetent greater saphenous vein. Am J Surg. 1994;168:311-315.

67. Belcaro G, Nicolaides AN, Ricci A, et al. Endovascular sclerotherapy, surgery, and surgery plus sclerotherapy in superficial venous incompetence: a randomized, 10-year follow-up trial—final results. Angiology. 2000;51:529-534.

68. Belcaro G, Cesarone MR, Di Renzo A, et al. Foam-sclerotherapy, surgery, sclerotherapy, and combined treatment for varicose veins: a 10-year, prospective, randomized, controlled, trial (VEDICO trial). Angiology. 2003;54:307-315.

69. de Roos KP, Nieman FH, Neumann HA. Ambulatory phlebectomy versus compression sclerotherapy: results of a randomized controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:221-226.

70. Bountouroglou DG, Azzam M, Kakkos SK, Pathmarajh M, Young P, Geroulakos G. Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy combined with saphenofemoral ligation compared to surgical treatment of varicose veins: early results of a randomised contolled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:93-100.

71. Liu X, Jia X, Guo W, et al. Ultrasoundguided sclerotherapy of the great saphenous vein with sapheno-femoral ligation compared to standard stripping: a prospective clinical study. Int Angiol. 2011;30:321-326.

72. Kalodiki E, Lattimer CR, Azzam M, Shawish E, Bountouroglou D, Geroulakos G. Long-term results of a randomized controlled trial on ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy combined with saphenofemoral ligation vs standard surgery for varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:451-457.

73. Figueiredo M, Araújo S, Barros N Jr, Miranda F Jr. Results of surgical treatment compared with ultrasoundguided foam sclerotherapy in patients with varicose veins: a prospective randomised study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:758-763.

74. Shadid N, Ceulen R, Nelemans P, et al. Randomized clinical trial of ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy versus surgery for the incompetent great saphenous vein. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1062-1070.

75. Wright D, Gobin JP, Bradbury AW, et al; VarisolveR European Phase III Investigators Group. VarisolveR polidocanol microfoam compared with surgery or sclerotherapy in the management of varicose veins in the presence of trunk vein incompetence: European randomized controlled trial. Phlebology. 2006;21:180-190.

76. Biemans AA, Kockaert M, Akkersdijk GP, et al. Comparing endovenous laser ablation, foam sclerotherapy, and conventional surgery for great saphenous varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:727-734.

77. Brittenden J, Cotton SC, Elders A, et al. A randomized trial comparing treatments for varicose veins. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1218-1227.

78. Tassie E, Scotland G, Brittenden J, et al; CLASS Study Team. Cost-effectiveness of ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy, endovenous laser ablation or surgery as treatment for primary varicose veins from the randomized CLASS trial. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1532-1540.

79. Rasmussen LH, Lawaetz M, Bjoern L, Vennits B, Blemings A, Eklof B. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, foam sclerotherapy and surgical stripping for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1079-1087.

80. Rasmussen L, Lawaetz M, Serup J, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, foam sclerotherapy and surgical stripping for great saphenous varicose veins with 3-year follow-up. J Vasc Surg: Venous Lym Dis. 2013;1:349-356.

81. Woźniak W, Mlosek RK, Ciostek P. Assessment of the efficacy and safety of steam vein sclerosis as compared to classic surgery in lower extremity varicose vein management. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2015;10:15- 24.

82. Yang L, Wang XP, Su WJ, Zhang Y, Wang Y. Randomized clinical trial of endovenous microwave ablation combined with high ligation versus conventional surgery for varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46:473- 479.

83. Campanello M, Hammarsten J, Forsberg C, Bernland P, Henrikson O, Jensen J. Standard stripping versus long saphenous vein–saving surgery for primary varicose veins: a prospective, randomized study with the patients as their own controls. Phlebology. 1996;11:45-49.

84. Hammarsten J, Pederson P, Cederlund CG, Campanello M. Long saphenous vein saving surgery for varicose veins: a long-term follow-up. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1990;4:361-364.

85. Hammarsten J, Campanello M, Pederson P. Long saphenous vein saving surgery for varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1993;7:763-764.

86. Winterborn RJ, Foy C, Earnshaw JJ. Causes of varicose vein recurrence: late results of a randomized controlled trial of stripping the long saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:634-639.

87. Almeida JI, Kaufman J, Göckeritz O, et al. Radiofrequency endovenous ClosureFAST versus laser ablation for the treatment of great saphenous reflux: a multicenter, single-blinded, randomized study (RECOVERY study). J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:752-759.

88. Shepherd AC, Gohel MS, Brown LC, Metcalf MJ, Hamish M, Davies AH. Randomized clinical trial of VNUS ClosureFAST radiofrequency ablation versus laser for varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2010;97:810-818.

89. Gale SS. Lee JN, Walsh ME, Wojnarowski DL, Comerota AJ. A randomized, controlled trial of endovenous thermal ablation using the 810-nm wavelength laser and the ClosurePLUS radiofrequency ablation methods for superficial venous insufficiency of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:645-650.

90. Goode SD, Chowdhury A, Crockett M, et al. Laser and radiofrequency ablation study (LARA study): a randomised study comparing radiofrequency ablation and endovenous laser ablation (810 nm). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40:246-253.

91. Nordon IM, Hinchliffe RJ, Brar R, et al. A prospective double-blind randomized controlled trial of radiofrequency versus laser treatment of the great saphenous vein in patients with varicose veins. Ann Surg. 2011;254:876-881.

92. Doganci S, Demirkilic U. Comparison of 980 nm laser and bare-tip fibre with1470 nm laser and radial fibre in the treatment of great saphenous vein varicosities: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40:254-259.

93. Lane TR, Kelleher D, Shepherd AC, Franklin IJ, Davies AH. Ambulatory varicosity avulsion later or synchronized (AVULS): a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2015;261:654-661.

94. Disselhoff BC, der Kinderen DJ, Moll FL. Is there a risk for lymphatic complications after endovenous laser treatment versus cryostripping of the great saphenous vein? A prospective study. Phlebology. 2008;23:10-14.

95. Disselhoff BC, der Kinderen DJ, Kelder JC, Moll FL. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser with cryostripping for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1232-1238.

96. Disselhoff BC, Buskens E, Kelder JC, der Kinderen DJ, Moll FL. Randomized comparison of costs and costeffectiveness of cryostripping and endovenous laser ablation for varicose veins: 2-year results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:357-363.

97. Lattimer CR, Kalodiki E, Azzam M, Geroulakos G. Validation of a new duplex derived haemodynamic effectiveness score, the saphenous treatment score, in quantifying varicose vein treatments. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43:348-354.

98. Lattimer CR, Azzam M, Kalodiki E, Shawish E, Trueman P, Geroulakos G. Cost and effectiveness of laser with phlebectomies compared with foam sclerotherapy in superficial venous insufficiency. Early results of a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43:594-600.

99. Lattimer CR, Kalodiki E, Azzam M, Makris GC, Somiayajulu S, Geroulakos G. Interim results on abolishing reflux alongside a randomized clinical trial on laser ablation with phlebectomies versus foam sclerotherapy. Int Angiol. 2013;32:394-403.

100. van der Bos RR, Malskat WS, De Maeseneer MG, et al. Randomized clinical trial of endovenous laser ablation versus steam ablation (LAST trial) for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1077-1083.

101. Kabnick LS. Outcome of different endovenous laser wavelengths for great saphenous vein ablation. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:88-93.

102. Disselhoff BC, der Kinderen DJ, Kelder JC, Moll FL. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein with and without ligation of the sapheno-femoral junction: 2-year results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:713-718.

103. Disselhoff BC, der Kinderen DJ, Kelder JC, Moll FL. Five-year results of a randomised clinical trial of endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein with and without ligation of the saphenofemoral junction. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41:685-690.

104. Theivacumar NS, Dellagrammaticas D, Mavor AI, Gough MJ. Endovenous laser ablation: does standard aboveknee great saphenous vein ablation provide optimum results in patients with above- and below-knee reflux? A randomized controlled trial. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:173-178.

105. Hogue RS, Schul MW, Dando CF, Erdman BE. The effect of nitroglycerin ointment on great saphenous vein targeted venous access size diameter with endovenous laser treatment. Phlebology. 2008;23:222-226.

106. Pannier F, Rabe E, Maurins U. 1470 nm diode laser for endovenous ablation (EVLA) of incompetent saphenous veins–a prospective randomized pilot study comparing warm and cold tumescence anesthesia. Vasa. 2010;39:249-255.

107. Dumantepe M, Uyar I. Comparing cold and warm tumescent anesthesia for pain perception during and after the endovenous laser ablation procedure with 1470 nm diode laser. Phlebology. 2015;30:45-51.

108. Vuylsteke M, De Bo T, Dompe G, Di Crisci D, Abbad C, Mordon S. Endovenous laser treatment: is there a clinical difference between using a1500 nm and a 980 nm diode laser? A multicenter randomised clinical trial. Int Angiol. 2011;30:327-334.

109. Vuylsteke ME, Thomis S, Mahieu P, Mordon S, Fourneau I. Endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein using a bare fibre versus a tulip fibre: a randomised clinical trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44:587-592.

110. Bakker NA, Schieven LW, Bruins RM, van den Berg M, Hissink RJ. Compression stockings after endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46:588-592.

111. Samuel N, Wallace T, Carradice D, Mazari FA, Chetter IC. Comparison of 12-w versus 14-w endovenous laser ablation in the treatment of great saphenous varicose veins: 5-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2013;47:346-352.

112. Kahle B, Leng K. Efficacy of sclerotherapy in varicose veins–a prospective, blinded, placebo-controlled study. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:723-728.

113. Hamel-Desnos C, Desnos P, Wollmann JC, Ouvry P, Mako S, Allaert FA. Evaluation of the efficacy of polidocanol in the form of foam compared with liquid form in sclerotherapy of the greater saphenous vein: initial results. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1170-1175.

114. Yamaki T, Nozaki M, Iwasaki S. Comparative study of duplex-guided foam sclerotherapy and duplex-guided liquid sclerotherapy for the treatment of superficial venous insufficiency. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:718-722.

115. Alòs J, Carreño P, López JA, Estadella B, Serra-Prat M, Marinel-Lo J. Efficacy and safety of sclerotherapy using polidocanol foam: a controlled clinical trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:101-107.

116. Ouvry P, Allaert FA, Desnos P, Hamel- Desnos C. Efficacy of polidocanol foam versus liquid in sclerotherapy of the great saphenous vein: a multicentre randomised controlled trial with a 2-year follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:366-370.

117. Rabe E, Otto J, Schliephake D, Pannier F. Efficacy and safety of great saphenous vein sclerotherapy using standardised polidocanol foam (ESAF): a randomised controlled multicentre clinical trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:238-245.

118. Yamaki T, Hamahata A, Soejima K, Kono T, Nozaki M, Sakurai H. Prospective randomised comparative study of visual foam sclerotherapy alone or in combination with ultrasoundguided foam sclerotherapy for treatment of superficial venous insufficiency: preliminary report. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43:343-347.

119. Hamel-Desnos CM, Gillet JL, Desnos PR, Allaert FA. Sclerotherapy of varicose veins in patients with documented thrombophilia: a prospective controlled randomized study of 105 cases. Phlebology. 2009;24:176-182.

120. Hamel-Desnos C, Allaert FA, Benigni JP, et al; Société Française de Phlébologie. Study 3/1. Polidocanol foam 3% versus 1% in the great saphenous vein: early results [in French]. Phlébologie. 2005;58:165-173.

121. Ceulen RP, Bullens-Goessens YI, Pi-Van De Venne SJ, Nelemans PJ, Veraart JC, Sommer A. Outcomes and side effects of duplex-guided sclerotherapy in the treatment of great saphenous veins with 1% versus 3% polidocanol foam: results of a randomized controlled trial with1-year follow-up. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:276-281.

122. Hamel-Desnos C, Ouvry P, Benigni JP, et al. Comparison of 1% and 3% polidocanol foam in ultrasound guided sclerotherapy of the great saphenous vein: a randomised, double-blind trial with 2 year-follow-up: “the 3/1 study.” Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:723-729.

123. Blaise S, Bosson JL, Diamand JM. Ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy of the great saphenous vein with 1% vs. 3% polidocanol foam: a multicentre double-blind randomised trial with 3-year follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:779-786.

124. O’Hare JL, Stephens J, Parkin D, Earnshaw JJ. Randomized clinical trial of different bandage regimens after foam sclerotherapy for varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2010;97:650-656.

125. Hamel-Desnos CM, Guias BJ, Desnos PR, Mesgard A. Foam sclerotherapy of the saphenous veins: randomized controlled trial with or without compression. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:500-507.

126. Hamel-Desnos CM, Desnos PR, Ferre B, Le Querrec A. In vivo biological effects of foam sclerotherapy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:238-245.

127. Almeida JI, Javier JJ, Mackay E, Bautista C, Proebstle TM. First human use of cyanoacrylate adhesive for treatment of saphenous vein incompetence. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2013;1:174-180.

128. Elias S, Lam YL, Wittens CH. Mechanochemical ablation: status and results. Phlebology. 2013;28(suppl 1):10-14.

129. van Eekeren RR, Boersma D, Elias S, et al. Endovenous mechanochemical ablation of great saphenous vein incompetence using the ClariVein_ device: a safety study. J Endovasc Ther. 2011;18:328-334.

130. Boersma D, van Eekeren RR, Werson DA, van der Waal RI, Reijnen MM, de Vries JP. Mechanochemical endovenous ablation of small saphenous vein insufficiency using the ClariVein_ device: one-year results of a prospective series. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;45:299-303.

131. Eklof B, Perrin M, Delis K, Rutherford RB, Gloviczki P. Updated terminology of chronic venous disorders: the VEINTERM transatlantic interdisciplinary consensus document. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:498-501.

132. Perrin MR, Guex JJ, Ruckley CV, et al; REVAS Group. Recurrent varices after surgery (REVAS), a consensus document. Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;8:233-245.

133. Vasquez MA, Rabe E, McLafferty RB, et al; American Venous Forum Ad Hoc Outcomes Working Group. Revision of the venous clinical severity score: venous outcomes consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:1387-1396.

134. Vasquez MA, Munschauer CE. Venous clinical severity score and quality-of-life assessment tools: application to vein practice. Phlebology. 2008;23:259-275.

135. Shepherd AC, Gohel MS, Lim CS, Davies AH. A study to compare disease-specific quality of life with clinical anatomical and hemodynamic assessments in patients with varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:374-382.

136. Guex JJ. Patient-reported outcome or physician-reported outcome? Phlebology. 2008;23:251.

137. Fischer R, Linde N, Duff C. Cure and reappearance of symptoms of varicose veins after stripping operation: a 34 year follow-up. J Phlebology. 2001;1:49-60.

138. van Rij AM, Jiang P, Solomon C, Christie RA, Hill GB. Recurrence after varicose vein surgery: a prospective long-term clinical study with duplex ultrasound scanning and air plethysmography. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:935-943.

139. Kostas T, Ioannou CV, Toulouopakis E, et al. Recurrent varicose veins after surgery: a new appraisal of a common and complex problem in vascular surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27:275-282.

140. Merchant RF, Pichot O; Closure Study Group. Long-term outcomes of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration of saphenous reflux as a treatment for superficial venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:502-509.

141. van den Bos R, Arends L, Kockaert M, Neumann M, Nijsten T. Endovenous therapies of lower extremity varicosities: a meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:230-239.

142. Brar R, Nordon IM, Hinchliffe RJ, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. Surgical management of varicose veins: metaanalysis. Vascular. 2010;18:205-220.

143. Murad MH, Coto-Yglesias F, Zumaeta- Garcia M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the treatments of varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(suppl 5):49S-65S.

144. Nesbitt C, Eifell RK, Coyne P, Badri H, Bhattacharya V, Stansby G. Endovenous ablation (radiofrequency and laser) and foam sclerotherapy versus conventional surgery for great saphenous vein varices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD005624.

145. Tellings SS, Ceulen RP, Sommer A. Surgery and endovenous techniques for the treatment of small saphenous varicose veins: a review of the literature. Phlebology. 2011;26:179-184.

146. Siribumrungwong B, Noorit P, Wilasrusmee C, Attia J, Thakkinstian A. A systematic review and metaanalysis of randomised controlled trials comparing endovenous ablation and surgical intervention in patients with varicose vein. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44:214-223.

147. Puggioni A, Lurie F, Kistner RL, Eklof B. How often is deep venous reflux eliminated after saphenous vein ablation? J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:517- 521.

148. Guarnera G, Furgiuele S, Di Paola FM, Camilli S. Recurrent varicose veins and primary deep venous insufficiency: relationship and therapeutic implications. Phlebology. 1995;10:98- 102.

149. Perrin MR. Results of deep-vein reconstruction. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1997;31:273-275.

150. Campbell WA, West A. Duplex ultrasound audit of operative treatment of primary varicose veins. In: Negus D Jantet G, Coleridge-Smith PD, eds. Phlebology ‘95. London, UK: Springer; 1995:407-409.

151. Stuart WP, Adam DJ, Allan PL, Ruckley CV, Bradbury AW. Saphenous surgery does not correct perforator incompetence in the presence of deep venous reflux. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:834-838.

152. Al-Mulhim AS, El-Hoseiny H, Al- Mulhim FM, et al. Surgical correction of main stem reflux in the superficial venous system: does it improve the blood flow of incompetent perforating veins? World J Surg. 2003;27:793-796.

153. van Gent WB, Wittens CHA. Influence of perforating vein surgery in patients with venous ulceration. Phlebology. 2015;30:127-132.

154. Mendes RR, Marston WA, Farber MA, Keagy BA. Treatment of superficial and perforator venous incompetence without deep venous insufficiency: is routine perforator ligation necessary? J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:891-895.

155. Perrin M. Presence of varices after operative treatment: a review (Part 2). Phlebolymphology. 2015;22:5-11.

156. Rabe E, Breu FX, Cavezzi A, et al; Guideline Group. European guidelines for sclerotherapy in chronic venous disorders. Phlebology. 2014;29:338- 354.

157. Kakkos SK, Bountouroglou DG, Azzam M, Kalodiki E, Daskalopoulos M, Geroulakos G. Effectiveness and safety of ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy for recurrent varicose veins: immediate results. J Endovasc Ther. 2006;13:357-364.

158. Darvall KA, Bate GR, Adam DJ, Silverman SH, Bradbury AW. Duplex ultrasound outcomes following ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy of symptomatic recurrent great saphenous varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:107-114.

159. Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, Dalsing MC, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(suppl 5):2S-48S.

160. Lugli M, Maleti O, Perrin M. Review and comment of the 2011 clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. Phlebolymphology. 2012;19:107- 120.

161. Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Eklof B, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs–guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int Angiol. 2014;33:87-208.

162. Pavlović MD, Schuller-Petrović S, Pichot O, et al. Guidelines of the First International Consensus Conference on Endovenous Thermal Ablation for Varicose Vein Disease: ETAV Consensus Meeting 2012. Phlebology. 2015;30:257-273.

163. Wittens C, Davies AH, Baekgaard N, et al. Management of chronic venous disease. clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49:678-737.

164. Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines: report from an American College of Chest Physicians Task Force. Chest. 2006;129:174-181.

165. Perk J, De Backer G, Gohlke H, et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1635-1701.

166. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Varicose veins: diagnosis and management. NICE guidelines [CG168]. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ cg168/chapter/1-recommendations. Published July 2013. Accessed January 19, 2016.

167. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Radiofrequency ablation of varicose veins. NICE interventional procedure guidance 8 [ipg8]. Available at: http://www.nice. org.uk/guidance/ipg8. Published September 2003. Accessed January 19, 2016.

168. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Endovenous laser treatment of the long saphenous vein. NICE interventional procedure guidance 52 [ipg52]. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ ipg52. Published March 2004. Accessed January 19, 2016.

169. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy for varicose veins. NICE interventional procedure guidance 440 [ipg440]. Available at: http://www.nice.org. uk/guidance/ipg440. Published February 2013. Accessed January 19, 2016.