Thrombosis and pulmonary embolism risk in patients undergoing varicose vein surgery

CH 3011, Bern, Switzerland

ABSTRACT

Varicose veins are not by themselves dangerous. Nevertheless, when treating them, it is important to prevent the occurrence of complications with potentially serious consequences such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Vein operations are among the procedures carrying the lowest risk of all surgical interventions. Publications on thromboembolism after vein surgery show a striking discrepancy in the number of reported cases of thromboembolism, which is partially due to the different methods used to record them.

Most thromboses are localized in the calf and their damage potential is limited, which has made some authors question the need for antithrombotic prophylaxis. Moreover, it is still unclear what the appropriate duration for this prophylaxis should be. Vein surgery may induce superficial phlebitis, which is known to flare up after several weeks.

This article describes our continuously recorded data on the occurrence of clinical thromboembolic events in 8639 operations on 12724 legs. The conclusion is that an atraumatic operation, extensive mobilization, and appropriate antithrombotic prophylaxis are useful tools to reduce the risk of complications to well below 0.4%.

REPORTED DATA ON THE INCIDENCE OF THROMBOEMBOLISM AFTER VARICOSE VEIN SURGERY

The comparison of published data on thrombosis and pulmonary embolism following varicose vein surgery reveals an astonishing discrepancy of 1:350, ranging from 0.015%1 to 5.3%.2 There are even some reports (not discussed here!) boasting a rate of 0%! The reluctance of some surgeons to acknowledge—or even report—the occurrence of complications may play an important role here.

Nevertheless, even creditable reports suffer from a considerable observer bias, which is the consequence of the accuracy of investigation. After vein surgery, many patients show some minor local symptoms that can reveal a (probably inconsequential) small thrombosis (Figure 1). Technical and financial constraints make it impossible to apply all the available diagnostic methods in each and every case, unless a scientific investigation is being carried out to determine the exact number of events. Due to feasibility requirements, many studies on thromboembolism therefore only enroll patients with clinical symptoms and the figures obtained in those studies will thus be far below the figures that would be obtained by the systematic examination of all patients. (Figure 2)

Figure 1. Patient 24 hours after state-of-the-art surgery with

pin-stripping of the great saphenous vein and hook phlebectomy.

Temporary bruising may appear later in the distal thigh.

Figure 2. One day after surgery for varicose veins. The leg will be

bandaged for 4 days (day and night) after surgery. The bandages

will be replaced by elastics stockings for another 3 to 4 weeks.

Endovenous treatments require consecutive serial ultrasound checks to assess the result; in contrast to surgery, where these checks are not necessary and where smaller thromboses may remain unnoticed. This difference should be taken into account when comparing the two modalities for the development of thromboembolism.

The third point to consider is the steadily increasing sensitivity of the methods used to detect both thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The blurred pictures of pulmonary scintigraphy—the only method to investigate embolism in former times—gave too much leeway for interpretation, much in contrast to the current state-of-the art technique of helical computer tomography. The same is true for the detection of thromboses. Phlebography is an unpleasant invasive examination that doctors used to be reluctant to prescribe for minor problems. Moreover, it could not identify thromboses of the calf veins, which have actually been found, with the wide application of color duplex imagining, to account for a substantial proportion of all recorded thromboses.

HOW IMPORTANT ARE SMALL VEIN THROMBOSES?

The highest incidence of thrombosis, a staggering 5.3%, was given in the publication of Van Rij et al.2 The aim of this well-documented study was to determine the absolute number of vein thromboses occurring after stripping of the long saphenous vein. All patients were examined by color ultrasound preoperatively and again postoperatively after 2 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months. Ninety percent (90%) of the thromboses were found in the calf veins; 60% were asymptomatic. There was no pulmonary embolism in this series of 20 patients and, after 12 months, valvular dysfunction had been restored in 50% of them.

All in all this study shows that meticulous serial examination reveals an unexpected high rate of small vein thromboses, but at the same time it shows that— fortunately—most of them have little or no clinical impact. The question therefore arises of whether it is worthwhile detecting subclinical thromboses.

Is antithrombotic prophylaxis necessary after vein surgery ?

If there were only small thromboses, we also could omit antithrombotic prophylaxis after vein surgery. An interesting contribution to this topic is a French prospective study published in 2004,3 in which only 3.7% of the patients received prophylaxis. In this survey of 4206 operations, 17 thromboses were registered, which corresponds to a 0.40% rate. These results were assessed by clinical examination on day 1, day 8, and day 30 after surgery; ultrasound examination was carried out in the case of symptoms suggestive of deep vein thrombosis. Pulmonary embolism was observed in 1 patient (0.02%). The authors found an increased risk for thromboembolism after surgery of the short saphenous vein (3 times greater than for long saphenous vein interventions) and in repeat surgery (3 times greater than for primary interventions). Seventy one percent (71%) of the thromboses were confined to the calf veins, and 4 of them occurred in the group of 155 patients receiving antithrombotic prophylaxis.

The authors concluded that prophylaxis can be restricted to high-risk patients, which would save 44 euros per patient.

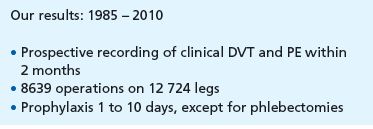

Our results from 1985 to 2010

Following the launch of my practice in 1985, I started prospectively and systematically to record all complications. The idea was to develop an internal quality control system to avoid the occurrence of similar complications in the future. It goes without saying that great importance was given to the recording of all symptomatic deep vein thromboses and pulmonary embolisms. Symptoms suggestive of thromboembolism were further investigated until a clear diagnosis could be made. The results were regularly updated for numerous oral presentations and occasionally published.4,5 The last update—covering 25 years of practice—was made in 2011 and included 8639 vein operations on 12 724 legs. With the exception of low-risk ambulatory phlebectomies, antithrombotic prophylaxis was administered to all patients for 1 to 10 days; this is much in contrast to the 3.7% in the above-mentioned French study. It is clear that in those 25 years, the antithrombotic agents as well as the diagnostic methods used to detect thromboembolism improved steadily.

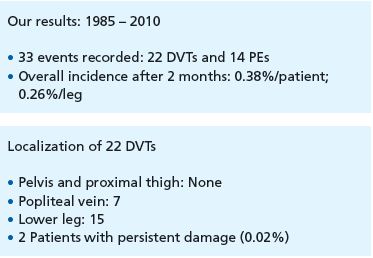

All patients underwent clinical examination 2 months after surgery. At the end of these 2 months, 33 events were recorded (22 thromboses and 14 pulmonary embolisms), corresponding to an overall incidence of 0.38% per patient, or 0.26% per operated leg. The 22 thromboses were localized as follows:

Compared with the French study mentioned above, the rates of bilateral operations as well as those of pulmonary embolisms are substantially higher, presumably an effect of different national insurance systems and of the availability of institutions specialized in the detection of emboli.

It is reassuring to see that there was not a single DVT in the groin. The proportion of calf vein thromboses has steadily increased. The 2 patients with persistent damage (one thombosis of the popliteal vein resulting in a slightly swollen leg, one homonymous hemianopsia, possibly due to crossed embolism) were operated in the late 1980s.

Another interesting finding that resulted from the 2-month observation period was that 24 of the 33 events occurred in the first 4 weeks following the procedure and that another 9 PEs (27%) were recorded in the second month, raising the question of how long prophylaxis should be administered for.

How long are patients at risk for thromboembolism after surgery ?

Every treatment on the superficial veins induces a limited superficial phlebitis at its borders, which may propagate into the deep venous system. This localized effect is demonstrated with statistical significance by the fact that all 22 thromboses were localized in the operated legs.

The progression of superficial phlebitis was investigated in 2003 in the Stenox study,6 which showed that this process persists for at least 3 months with a rebound effect after withdrawal of low-molecular-weight heparin after 10 days—in fact, patients treated with a much cheaper oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent eventually showed identical results. In the 2010 Calisto Study, the antithrombotic prophylaxis was extended to 45 days and a clear advantage was demonstrated.7

But can our health care systems afford such a high-priced approach considering the relatively few complications of this type of surgery?

Personal interpretation and conclusions

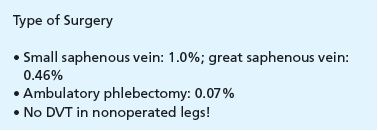

The risk of thromboembolism depends on various factors: coagulation disorders—which often go unnoticed until the first event occurs—age and the presence of concomitant diseases, and finally the extent and duration of the surgical intervention. It is generally accepted that small saphenous vein (SSV) surgery carries a greater thrombotic risk than GSV surgery; in our survey, this ratio was 2:1 (1% for SSV operations, 0.46% for GSV operations); at the opposite end of the spectrum, the risk after ambulatory phlebectomy is only 0.07%.

The topic of postoperative thromboembolism (and other possible complications) should be discussed well in advance with every patient, in particular to protect the surgeon against litigation. It is my impression that anxious patients who worry about pulmonary embolism seem to attract this complication. The worst thing to do would be to omit prophylaxis in this group of patients.

Prophylaxis is not restricted to the use of pharmacological agents, it also includes early and extensive mobilization, which requires careful attention from the surgeon in order to minimize postoperative pain and immobility.

Hook phlebectomy and pin-stripping have substantially diminished postoperative bruising and pain (Figures 1 and 2). Today, only 1 out of 4 patients needs painkillers after being discharged from hospital, which allows for a painless and extensive mobilization. I used to tell my patients to walk two or three times a day; now I encourage them to walk as much as possible, which seems to be beneficial in lowering the thrombotic risk and also shortens the period of disability, which actually amounts to just 7 days for bilateral stripping.8

REFERENCES

1. Frings N, Glowacki P, Subasinghe C. Major complications of varicose veins surgery (Major-Komplikationen in der Varizenchirurgie). Phlebologie. 2001;2:31- 35. [in German]

2. Van Rij A, Chai J, Hill GB, et al. Incidence of deep vein thrombosis after varicose vein surgery. Br J Surg. 2004;91(12):1582- 1585.

3. Lemasle P, Lefebvre-Vilardebo M, Uhl JF, et al. Faut-il vraiment prescrire des anticoagulants après chirurgie d’exérèse des varices? [Is it mandatory to prescribe anticoagulants after stripping surgery for varicose veins?] Phlébologie. 2004;57:187- 194.

4. Oesch A. Tiefe Venenthrombosen und Lungenembolien nach Varizenoperationen [Incidence of vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after varicose vein surgery]. VASA. 1999;28:233.

5. Oesch A. Les éveinages de la petite veine saphène à l’aide du pin stripper [Small saphenous vein ablation using pin stripper]. J Méd Esth Chir Derm. 2001;28:191- 194.

6. Superficial Thrombophlebitis Treated by Enoxoparine Study Group. A pilot randomized double-blind comparison of a low-molecular-weight heparin, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammmatory agent and placebo in the treatment of superficial vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1657-1663.

7. Decousus H, Prandoni P, Mismetti P, et al. CALISTO Study Group. Fondaparinux for the treatment of superficial vein thrombosis of the legs. New Engl J Med. 2010;363(13):1222-1232.

8. Oesch A. Arbeitsunfähigkeit und Schmerzmittelbedarf nach grösseren Varizenoperationen [Inability to work and demand for analgesics after vein surgery]. Wiener Med Wochenzeitschrift. 2010;160(suppl 123):9.