State of art in lymphedema management: part 2

Lymphedema and Vascular Malformation,

George Washington University School of

Medicine

Abstract

Chronic lymphedema can be managed effectively using a sequenced and targeted treatment program based on decongestive lymphatic therapy (DLT) with compression therapy and surgery (mostly as an adjunct to DLT). In the maintenance phase, DLT is carried out using the proper combination of compression garments, meticulous personal hygiene and skin care, self-massage based on the principle of manual lymphatic drainage (if applicable), and exercises and activities to promote lymph transport. Pneumatic compression devices and therapy can be applied at home, if desired. When conservative treatment based on DLT fails or delivers suboptimal outcomes, the patient may need additional surgical interventions, either reconstructive or ablative, where applicable. These two surgical therapies are more effective in terms of outcomes when combined postoperatively with manual lymphatic drainage–based DLT. A long-term commitment to postoperative DLT, especially compression therapy, is a critical factor in determining the success of either reconstructive or palliative surgery. Recently, several causal genetic mutations have been identified among primary lymphedema syndromes, which provide possible opportunities for future molecular interventions. This new prospect of gene-oriented management is more promising as a molecular therapy for both primary and acquired lymphedema.

Surgical treatment: reconstructive surgery

Currently, no treatments are available to provide a “cure” for lymphedema and all available treatments are so far limited to palliate the condition. However, in recent years, there has been a rapid evolution in surgical treatments using reconstructive methods with newly developed microsurgical techniques.1-4 Reconstructive surgery aims to restore lymphatic drainage with physiological methods by creating new lymphatic channels and to achieve an effective reduction in swelling, with the ultimate goal being to reduce the chance of infection as its ultimate goal.5-8 A new concept of surgical reconstruction of lymph vessels and lymph nodes has evolved rapidly over the last 50 years and various modalities of microsurgicallymphatic reconstructions were introduced based on anastomotic reconstruction of lymph vessels to veins9-12 and lymph nodes to veins,13-16 in addition to lymphatic grafting to bypass the lymphatic obstructions.17-20

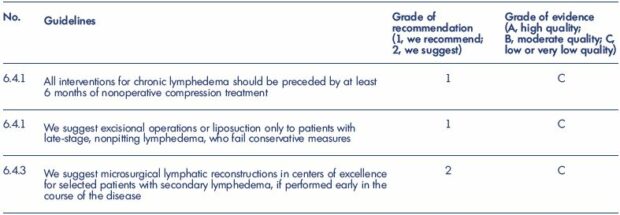

Table I. Guidelines of the American Venous Forum on surgical treatment of chronic Lymphedema.

From reference 40: Guidelines 6.4.0. on medical and physical therapy. In: Gloviczki P, ed. Handbook of Venous Disorders: Guidelines

of the American Venous Forum. 3rd Edition. London, UK: Hodder Arnold; 2009:663.

A lymphovenous bypass that drains into the venous circulation can be performed by anastomosing functioning lymphatic vessels located within a diseased area to the regional veins.21 A lymphatic-lymphatic bypass can also be done using an interposition graft to connect to healthy lymphatic channels beyond the affected region using a transplanted lymphatic vessel or vein.22 Among these three different types of lymphatic reconstructions, developed based on microsurgical and supermicrosurgical techniques, lymphovenous bypass and anastomosis have remained the most popular approach for decades.23-26 For many reasons, the interest in this logical approach that offers a chance of a “cure” have waxed and waned over the years. In particular, the technically demanding microsurgical techniques have hampered the widespread acceptance of this approach as a first-line treatment, meaning that this noble approach remained available only at specialized centers to provide an active lymphatic surgical reconstruction.

Recently, the new concept of “supermicrosurgery” rekindled the enthusiasm for lymphatic reconstructions with microsurgical and supermicrosurgical techniques.23-26 The popularity of lymphovenous or lymphaticovenular bypass and anastomosis has improved in recent years.14,27-29 In addition, the newly developed technique of vascularized lymph node transfer and transplantation (VLNT) as a free flap was a welcomed new approach with a more promising future,30-33 especially for the candidates who failed to meet the indication for conventional anastomotic reconstruction. Together with lymphaticovenular anastomosis, VLNT is the most commonly practiced procedure today.

So far, reconstructive surgery with various microsurgical lymphovenous anastomoses can deliver the best outcome when performed in clinical stage I and II (early stage) before the progression to the advanced fatty fibrous stages.34,35 Reconstructive surgery with autologous free lymph node transplant surgery also provides a promising future for patients with primary lymphedema in clinical stage II and III with defective lymph nodes, particularly lymphadenodysplasia.36-39

Nevertheless, the majority of the data that is available for thorough review belong to grade 2B or 2C when assessed using the system developed by Guyatt et al, and, at best, only a small number belong to grade 1C or 2A because of the unique condition of observational studies, as discussed in Part 1 (1. Introduction:1-1. Background) (Table 140).

Reconstructive surgery is often considered as an additional procedure to improve the efficacy of the management when manual lymphatic drainage (MLD)–based DLT fails to prevent a steady progress of the condition with no response to a maximum of MLD-based DLT for a minimum 6 months.41,42 However, its indication should be extended further to the patients with multiple recurrent episodes of cellulitis and/or lymphangitis, chylous-reflux combined with extremity lymphedema, and poor tolerance to DLT-based treatment physically, mentally, and socioeconomically. In addition, reconstruction can be performed as a preventive measure when the excision of major lymph nodes for malignancy should carry a high likelihood of developing subsequent lymphedema.1,2

Early stage lymphedema is an ideal period for reconstructive surgery and unnecessarily delaying surgical intervention for more than 1 year will definitely allow further damage of the lymphatic vessel, especially its contractibility, and increase the risk of surgical failure. Therefore, the timing of lymphatic reconstruction is crucial and this waiting period should be shortened whenever possible to avoid permanent damage of the lymphatic vessels, thus making lymphatic reconstruction futile.1,2 In general, advanced stages of chronic lymphedema will show a poor response, with the poorest candidate for reconstruction being primary lymphedema caused by hypoplasia or aplasia of the lymph vessels with lymphatic fibrosis.

The current policy to delay lymphatic reconstruction until the failure of maximal DLT-based therapy for a substantial period has been confirmed to cause further damage to the lymphatic system, which will increase the risk of procedure failure. In fact, the majority of patients who receive lymphatic reconstruction already have significant damage due to long-term lymphatic obstruction and hypertension. Therefore, postoperative DLT is essential to maintain good long-term outcomes following successful reconstructive surgery on these partly damaged lymph vessels.3,4 The single most important factor to maintain a successful outcome is “patient compliance” with a life-long commitment to DLT, especially when the surgery is done after a substantial delay while waiting for DLT-based therapy to fail.8,34

In addition, a timely intervention for systemic and local infections, such as cellulitis and erysipelas, are equally as important in preventing further injury to already damaged lymph vessels before surgery.42 While the benefits of reconstructive surgery are maximal when performed at an “early” stage of lymphedema with a chance of full restoration of paralyzed lymph vessel function, the procedure is still beneficial when performed at a “late” stage, because increasing lymph flow subsequently improves immune response, which decreases the overall risk of infection.43

Secondary lymphedema is generally more suitable for lymphatic reconstructions since surgically correctable conditions present along the major lymphatics with documented proximal (pelvic, axillary) lymphatic obstruction, while distal lymphatics remain patent.44-47 However, primary lymphedema presents with extremely variable forms (eg, aplasia, hypoplasia, and hyperplasia) and with variable extents of dysplastic conditions (eg, lymphangiodysplasia, lymphadenodysplasia, and lymph-angio-adenodysplasia) as a truncular lymphatic malformation. Therefore, proper conditions for reconstruction are rare and the outcomes of surgery are generally not as effective as among those with secondary lymphedema.48-50 Nevertheless, excellent results have been reported, even in primary lymphedema, with suitable lymph vessels for the reconstruction with a prevailing condition of lymphadenodysplasia rather than lymphangiodysplasia.48,50

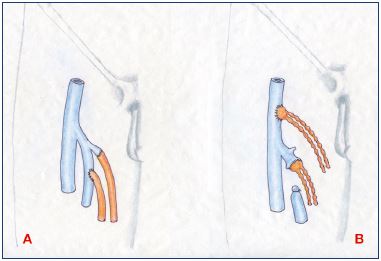

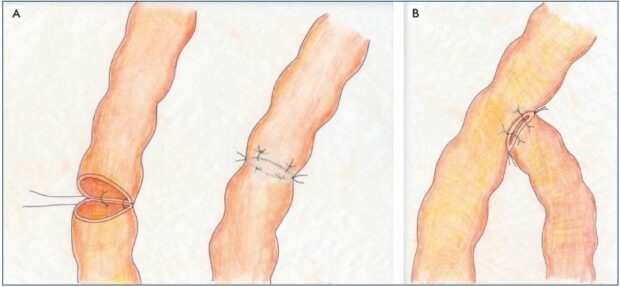

Lymphaticovenular anastomosis aims to drain lymph directly into the venous system through an anastomosis between lymphatic vessels and the vein to relieve distal lymphatic obstruction caused by acquired or primary iliac lymphatic obstruction.51-54 However, occasionally, lymphaticovenular anastomosis can be successfully used for congenital lymphangiectasia.54,55 Lymphaticovenular anastomosis is ideal for patients after excision of proximal lymph nodes for cancer treatment.51-54 Most microvascular surgeons perform lymphovenous or lymphaticovenular bypass with direct end-to-end or end-toside anastomoses to create new channels between subdermal lymphatic vessels and adjacent venules (<0.8 mm) using high power magnification and 8–11/0 microsutures (Figures 1 and 2).9,10,21

Figure 1. Lymphovenous anastomosis.

Panel A. Microsurgical technique of direct anastomosis in endto-

end and end-to-side fashion for lymphatic vessels-to-vein

anastomosis at the groin. Panel B. End-to-end and end-to-side

techniques for lymph node-to-vein anastomosis, another form

of lymphovenous anastomosis.

Figure 1. Lymphovenous anastomosis.

Panel A. Microsurgical technique of direct anastomosis in endto-

end and end-to-side fashion for lymphatic vessels-to-vein

anastomosis at the groin. Panel B. End-to-end and end-to-side

techniques for lymph node-to-vein anastomosis, another form

of lymphovenous anastomosis.

So far, lymphaticovenular anastomosis is a well-accepted procedure, especially in the early stages of lymphedema (stages I and II),1,2 yielding better results with an average patency rate of 50% at 3 to 8 months after surgery.10,11 However, its clinical effectiveness is difficult to assess since almost all studies in published series are uncontrolled and combined with adjuvant compression therapy (Figure 3). Nevertheless, secondary lymphedema shows better results than primary lymphedema in general. A meta-analysis of outcomes after lymphaticovenular anastomosis have shown that 89% of patients had a subjective improvement, 88% of patients had a quantitative improvement, and 56% of patients were able to discontinue compression therapy based on pooled results from 22 studies.56

Lymphatic grafting was also introduced to relieve localized obstruction or interruption of lymph nodes and/or lymph vessels of either secondary or primary origin.57 This procedure is ideal for mild-to-moderate upper extremity lymphedema with minimal fibrosis and a moderate number of functioning lymphatics.58

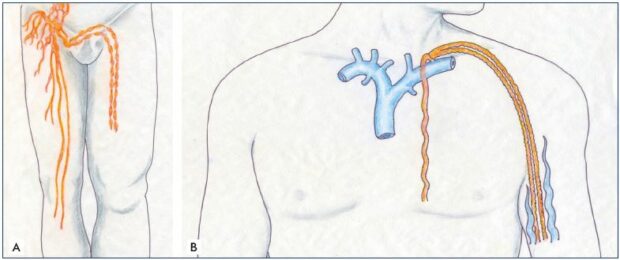

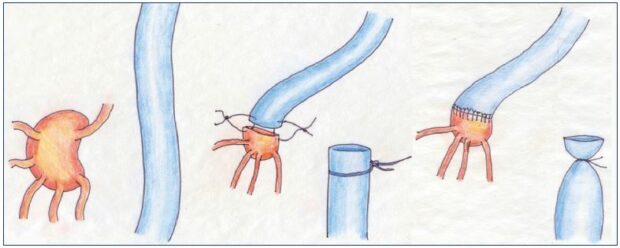

Secondary lymphedema due to a locally interrupted lymphatic system is the main indication for lymphatic grafting.18,59 Arm edema after axillary node dissection or leg edema after interventions in the inguinal or pelvic region can be treated by transposing lymphatic vessels from the healthy to the affected side. Lymphatic grafting has a unique role in bypassing lymphatic obstruction. Two to three lymph vessels are harvested from the unaffected lower limb out of the perisaphenous superficial lymphatic bundles, and either a free graft is used for the axillary lymphatic obstruction due to postmastectomy lymphedema (Figure 4A) or a suprapubic cross-femoral transposition graft is used for iliac or iliofemoral lymphatic obstruction to relieve unilateral lower limb lymphedema (Figure 4B).17

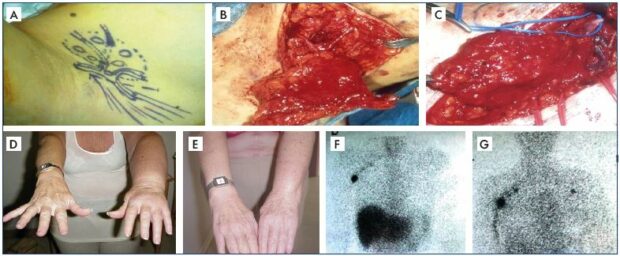

Figure 3. Clinical case of lymphovenous anastomosis.

Panel A. Preoperative drawing of an anastomotic site for reconstructive lymphatic surgery with multiple lymphovenous

anastomoses at the popliteal level (Krylov’s method). Panel B. Presentation of the operative field to prepare for direct anastomoses

between functioning lymph vessels and a defunctionalized vein. Panel C. Preoperative lymphedema status. Panel D. Postoperative

status with clinical improvement in lymphedema following successful lymphaticovenular anastomosis. Panel E. Also shows

preoperative lymphoscintigraphic findings showing diffuse dermal backflow to confirm advanced lymphatic dysfunction. Panel F.

Shows postoperative lymphoscintigraphic findings to confirm remarkable improvement following successfully restored lymphatic

function by lymphaticovenular anastomosis.

Figure 4. Lympho-lymphatic bypass surgery.

Panel A. Transplantation and transposition technique of two lymph channels and vessels, which were harvested from the lower

extremity and transplanted on the upper extremity to bypass the axillary lymphatic obstruction and treat the postmastectomy

lymphedema. Panel B. Cross-femoral lymph vessel transposition for unilateral lower extremity lymphedema.

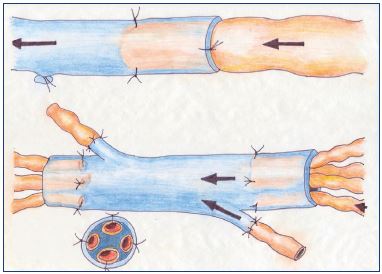

End-to-end or end-to-side anastomoses can be performed with 10-0 absorbable suture material using a “tension-free” technique to establish lymph flow to the healthy side via the grafts (Figures 5). Despite tedious operations,57 the long-term results have shown an excellent improvement in limb volume reduction in 80% of patients (mean follow up of 3 years).18 Transposed suprapubic lymph vessels have also been well documented for their patency with lymphoscintigraphy.19

Figure 5. Lympho-lymphatic anastomoses.

Panel A. Lymphatico-lymphatic end-to-end anastomosis using a tension-free technique without turning the vessel. Panel B. Lympholymphatic

end-to-side anastomosis using the same technique.

Figure 6. Lymph node-to-venous anastomosis.

The procedure from the preparation of the vein for lymph node—venous bypass to the subsequent anastomosis of transected

lymph nodes directly to the vein segment to establish a microsurgical technique.

Lymph node-to-vein bypass is performed as end-to-end or end-to-side anastomoses between transected inguinal lymph nodes and saphenous or femoral veins (Figures 1A and 6).15 However, except for results from a few uncontrolled studies, the scarring over the cut surface of the lymph nodes often failed to provide a long-term improvement.13,15 Therefore, this new approach failed to receive a widespread application in most types of secondary lymphedema except filariasis. Filariasis often causes an enlargement of lymphatic vessels, even within the lymph nodes, and high lymph flow. In patients with filariasis, lymph node-to-vein bypass gave good results in 90% of patients with parasitic lymphatic infections.22 Also, good results were obtained in patients with congenital lymphangiectasia after lymph node–venous shunts when constructed in the inguinal area.16,22

The VLNT procedure transplants healthy lymph nodes harvested from one region (eg, supraclavicular region) to the affected area by microsurgically connecting the lymph nodes to recipient vessels in the intended location. The procedure was originally done as an avascular graft,60 but it is now done by transferring the lymph nodes together with surrounding fat as part of a vascularized tissue flap. It is considered that the transferred nodes promote lymphangiogenesis and act as a lymphatic pump.61

VLNT is a way to make a bridge across the lymphatic obstruction for postmastectomy lymphedema, eg, by transferring lymph nodes harvested as a free flap from the groin by the anastomoses of the feeding artery and the draining vein to the appropriate vessels in the axillary fossa using standard microsurgical techniques.32,63 Donor sites to harvest lymph nodes for a free transfer include the superficial groin, supraclavicular, submental, thoracic, and omental groups.

VLNT can be performed either alone or as a combined procedure with lymphaticovenular anastomosis.58 However, VLNT is generally recommended for advanced conditions, ie, in grades II to IV lymphedema,63 although the greatest improvement was reported in the early stages of lymphedema. VLNT is therefore indicated as a choice when: (i) the local condition precludes lymphaticovenular anastomosis due to fibrosis; (ii) a total occlusion of the lymphatic vessels is evidenced on lymphoscintigraphy; and (ii) at stage II,64 with or without repeated episodes of cellulitis (Figure 7). Although the volume of the limb either decreased or returned to normal at 5 years or more after lymph node transplantation,32,62 only 31% were able to demonstrate activity of the transplanted nodes on isotopic lymphoscintigraphy. There are also some concerns about the potentially serious complication and risk of the donor site developing de novo lymphedema.58,62

VLNT can improve both lymphatic drainage and regional immunological function and resistance to infection. VLNT becomes the source of vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGF-C) and other cytokines that induce and regulate lymphangiogenesis.65,66 Increasing evidence shows that VLNT reverses the disease process to obviate the need for a lifelong commitment to DLT, etc.62 VLNT is now one of the two most popular microsurgical procedures to deliver improved lymphatic function successfully together with lymphaticovenular anastomosis as a reconstructive surgical modality. However, VLNT has been focusing on reducing the fluid volume of the lymphedema and failed to encounter existing fat hypertrophy and tissue fibrosis; the tissue damage that has already developed cannot be reversed completely.

Figure 7. Clinical case of vascularized lymph node transplantation.

Panel A. Schematic drawing of lymph nodes harvested from the right posterior axillary group with intact arteries and veins

for a free graft. Panel B. Actual operative field for the lymph node harvest with intact arteries and veins for a free graft. Panel C.

End-to-end anastomoses of donor and recipient arteries and veins. Panel D. Preoperative status of lymphedema. Panel E.

Postoperative status with remarkable clinical improvement in the following successful free lymph node graft. Panel F. Preoperative

lymphoscintigraphic findings with no visible lymph nodes in the left axilla. Panel G. Postoperative lymphoscintigraphic findings with

new lymph nodes appearing in the left axilla to confirm the successful vascularized lymph node transplantation.

Although surgical treatment of lymphedema is generally reserved only for when the condition becomes refractory to DLT, the paradigm has shifted toward earlier intervention with physiological surgery, such as VLNT and lymphaticovenular anastomosis.58 VLNT is expected to become the most suitable treatment modality with better prospects for primary lymphedema caused by the unique condition of lymphadenodysplasia.2

Surgical treatment: reductive and ablative surgery

Reductive surgical approaches are one of two surgical options, together with physiological approaches, that are performed alone or together. Reductive approaches aim to decrease the morbidity caused by excess volume of the affected limb by removing the fibrofatty tissue with direct excision methods or liposuction.2,67-70

Excisional and debulking surgery is generally offered as a supplemental measure of last resort for clinical stages III and IV (end stage) to improve the efficacy of available DLT.67-70 Once the lymphedema advances to late and end stage, steady progress of the condition results in massive limb changes by fibrotic induration despite aggressive DLT.68,71

Often, a highly disfigured swollen limb would not allow proper wrapping with a bandage to deliver effective compression to the local tissue. Subsequently, the condition would continue to progress to become irreversible with an increasing risk of local and systemic sepsis in the majority.

Since the early 1900s, various debulking operations were introduced to remove disfiguring, scarred, lymphedematous tissue from affected limbs.72-75 However, the indiscriminate use of these procedures generally resulted in poor outcomes,75-77 and, for many decades, they were virtually abandoned by the majority of surgeons due to the associated morbidity and questionable long-term efficacy.74,78 However, interest was rekindled recently after modifications were made to the original techniques, with improved outcomes (eg, the modified Auchincloss and Homan procedure).69,70

Excisional surgery has been resurrected for the treatment of lymphedema with limited application in patients with end stage chronic lymphedema as a supplemental treatment to failing DLT,2,68 the excision of fibrosclerotic soft tissue overgrowth improves the efficacy of subsequent DLT and compression bandaging.68,69 Excisional surgery can also be performed in advanced stages with no additional risk of injury to the remaining lymphatic vessels when associated with recurrent local and systemic sepsis that is refractory to maximum DLT.68,69 Hence, the indications should include progression of the disease to end stages despite maximum available treatment, increased frequency and/or severity of local and/or systemic sepsis, and failure to implement proper care at clinical stages III and IV (end stage) (Figure 8).1,2 The outcome of surgery is dependent on appropriate postoperative DLT.3,4 The patient’s compliance to keep postoperative maintenance DLT is a major critical issue for its long-term success. The initial excellence of the surgical achievements cannot be maintained without proper postoperative DLT. Surgery alone is highly likely to fail in the long term.68

Excisional surgery is a viable option to play a new supplemental role in the non- to poor-responding DLT group. As adjunctive therapy, it would improve the efficacy of DLT on the treatment of intractable end-stage lymphedema. Surgery and DLT have mutually complementary effects. Nevertheless, there is no consensus yet on the optimal timing of the intervention or the choice of procedure.

Liposuction is an additional debulking technique that is less radical than excisional surgery. The aim is to obliterate the epifascial compartment using a “circumferential” suction-assisted lipectomy instead of resecting the entire fibrosclerotic soft tissue overgrowth.74,79 Therefore, it avoids the complications and morbidity associated with the traditional open surgical method by using an excisional technique.74,79-81

Liposuction is a method to remove fat, not fluid, meaning that it should not be performed before DLT is used to transform pitting edema, which is caused by accumulated lymph, into nonpitting edema. Percutaneous liposuction removes excessive adipose tissue along with cannulas attached to vacuum suction during the adipofibrous (mid) stage (clinical stage II and III). Therefore, the patient who gets the most benefit from this procedure is the one who developed a unique condition of excess fat accumulation as a manifestation of the secondary lymphedema of the upper limb following breast cancer treatment.74,79 In addition, the control of the hydrostatic component of lymphedema should be done with conventional DLT before and after the liposuction.

Figure 8. Clinical case of a bilateral excisional and debulking surgery of the lower extremities.

Panel A. Clinical appearance of bilateral lower extremities with advanced lymphedema in clinical stage III before institution of

excisional surgery to make the local condition amenable to effective decongestive lymphatic therapy for better rehabilitation.

Panel B. Actual operative field for a debulking procedure to excise most of the soft tissue layer down to the muscle, including

the muscle fascia, using a modified Auchincloss approach to save the skin. Panel C. Shows the outcome of successful excisional

surgery on both lower extremities.

Liposuction was reported to be effective with significant long-term volume reduction in secondary lymphedema.82 However, many remain concerned with the risk of collateral damage to the viable lymph vessel system, since this procedure will have to be done for effective removal of adipose tissue in the early stages, while the remaining lymphatic system has substantial lymphatic function.1,2 The efficacy of liposuction has not been proven for primary lymphedema, a clinical manifestation of truncular lymphatic malformation, which has a completely different pathogenesis, ie, a congenital origin. The clinical course of primary lymphedema is not the same as that of secondary lymphedema, as it mostly affects the lower extremities; there is no proven evidence for selective overgrowth of the adipose tissue among this group, unlike that of the group with secondary lymphedema.38,39,45,47

Furthermore, primary lymphedema is a clinical manifestation of truncular lymphatic malformation with a significant risk for combined extratruncular lymphatic malformation. When a coexisting extratruncular lymphatic malformation is stimulated by liposuction, its mesenchymal cell characteristics would precipitate its rapid growth, making the condition worse.83-85

In primary lymphedema, the timing and safety risks of liposuction on the potential to exacerbate the condition by damaging residual functioning lymphatic channels remains to be established.45,47,86,87 This technique, however, can improve quality of life88,89 and reduce the incidence of erysipelas that is related to lymphedema among patients receiving breast cancer therapy, although it requires more vigorous compression therapy following the procedure and lifelong compression garments to prevent recurrence and maintain the reduced limb volume.87,90

Conclusion

A new concept of surgical reconstruction of lymph vessels and lymph nodes has been rapidly evolving throughout the last 50 years and various modalities of microsurgical lymphatic reconstructions were introduced based on anastomotic reconstruction of lymph vessels to veins and lymph nodes to veins in addition to lymphatic grafting to bypass the lymphatic obstructions. Among these three different types of lymphatic reconstructions, developed based on microsurgical techniques, lymphovenous bypass/ anastomosis has remained the most popular approach for decades. So far, reconstructive surgery with various microsurgical lymphovenous anastomoses can deliver the best outcome when performed in patients at clinical stages I and II (early stages) before the progression to the advanced fatty fibrous stages.

Reconstructive surgery with autologous free lymph node transplant surgery also provides a promising future for primary lymphedema in clinical stages II and III with defective lymph nodes, which is known as lymphadeno-dysplasia in particular. Reductive surgical approaches are one of two surgical options together with physiologic approaches, performed alone or together. Reductive approaches aim to decrease the morbidity caused by excess volume of the affected limb either by removing the fibrofatty tissue with direct excision methods or liposuction. Excisional surgery is a viable option to play a new supplemental role in the non- to poor-responding DLT group; as adjunctive therapy, it would improve the efficacy of DLT on the treatment of intractable lymphedema in the end stages. Surgery and DLT have mutually complementary effects. However, there is no consensus yet on either the optimal timing of the interventions or the choice of procedure.

Liposuction is an additional debulking technique that is a less radical approach than excisional surgery. The aim of liposuction is to obliterate the epifascial compartment by “circumferential” suction-assisted lipectomy, instead of resecting the entire fibrosclerotic soft tissue overgrowth. Therefore, it can avoid the complications and morbidity associated with the traditional open surgical method with excisional technique.

REFERENCES

1. Lee BB, Andrade M, Bergan J, et al; IUP. Diagnosis and treatment of primary lymphedema. Int Angiol. 2010;29(5):454- 470.

2. Lee BB, Andrade M, Antignani PL, et al; IUP. Diagnosis and treatment of primary lymphedema. Int Angiol. 2013;32(6):541- 574.

3. Lee BB, Kim DI, Whang JH, Lee KW. Contemporary issues in management of chronic lymphedema – personal reflection on an experience with 1065 patients. Commentary. Lymphology. 2005;38:28-31.

4. Lee BB. Contemporary issues in management of chronic lymphedema: personal reflection on an experience with 1065 patients. Lymphology. 2005;38(1):28-31.

5. Campisi C, Bellini C, Campisi C, Accogli S, Bonioli E, Boccardo F. Microsurgery for lymphedema: clinical research and long-term results. Microsurgery. 2010;30(4):256-260.

6. Campisi C, Eretta C, Pertile D, et al. Microsurgery for treatment of peripheral lymphedema: long-term outcome and future perspectives. Microsurgery. 2007;27(4):333-338.

7. Lee BB. Surgical management of lymphedema. In: Tredbar LL, Morgan CL, Lee BB, Simonian SJ, Blondeau B, eds. Lymphedema: Diagnosis and Treatment. London, UK: Springer; 2008:55-63.

8. Lee BB, Laredo J, Neville R. Reconstructive surgery for chronic lymphedema: a viable option, but. Vascular. 2011;19(4):195- 205.

9. Gilbert A, O’Brien BM, Vorrath JW, Sykes PJ. Lymphaticovenous anastomosis by microvascular technique. Br J Plast Surg. 1976;29(4):355-360.

10. Gloviczki P, Hollier LH, Nora FE, Kaye MP. The natural history of microsurgical lymphovenous anastomoses: an experimental study. J Vasc Surg. 1986;4(2):148-156.

11. Gloviczki P, Fisher J, Hollier LH, Pairolero PC, Schirger A, Wahner HW. Microsurgical lymphovenous anastomosis for treatment of lymphedema: a critical review. J Vasc Surg. 1988;7(5):647-652.

12. Campisi C, Boccardo F, Zilli A, Macciò A, Napoli F. Long-term results after lymphatic-venous anastomoses for the treatment of obstructive lymphedema. Microsurgery. 2001;21(4):135-139.

13. Olszewski WL. The treatment of lymphedema of the extremities with microsurgical lympho-venous anastomoses. Int Angiol. 1988;7(4):312- 321.

14. Olszewski WL. Lymphovenous microsurgical shunts in treatment of lymphedema of lower limbs: a 45- year experience of one surgeon/ one center. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;45(3):282-290.

15. Nielubowicz J, Olszewski W. Surgical lymphaticovenous shunts in patients with secondary lymphoedema. Br J Surg. 1968;55(6):440-442.

16. Jamal S. Lymph nodo-venous shunt in the treatment of protein losing enteropathy and lymphedema of leg and scrotum. Lymphology. 2007;40(1):47-48.

17. Baumeister RGH, Seifert J. Microsurgical lymphvessel-transplantation for the treatment of lymphedema: experimental and first clinical experiences. Lymphology. 1981;14(2):90.

18. Baumeister RG, Siuda S. Treatment of lymphedemas by microsurgical lymphatic grafting: what is proved? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85(1):64-74.

19. Weiss M, Baumeister RG, Hahn K. Dynamic lymph flow imaging in patients with oedema of the lower limb for evaluation of the functional outcome after autologous lymph vessel transplantation: an 8-year follow-up study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30(2):202-206.

20.Baumeister RG, Mayo W, Notohamiprodjo M, Wallmichrath J, Springer S, Frick A. Microsurgical lymphatic vessel transplantation. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2016;32(1):34-41.

21. Huang GK, Hu RQ, Liu ZZ, Shen YL, Lan TD, Pan GP. Microlymphaticovenous anastomosis in the treatment of lower limb obstructive lymphedema: analysis of 91 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:671-685.

22. Jamal S. Lymphovenous anastomosis in filarial lymphedema. Lymphology. 1981;14(2):64-68.

23. Koshima I, Inagawa K, Urushibara K, Moriguchi T. Supermicrosurgical lymphaticovenular anastomosis for the treatment of lymphedema in the upper extremities. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2000;16(6):437-442.

24. Narushima M, Mihara M, Yamamoto Y, et al. The intravascular stenting method for treatment of extremity lymphedema with multiconfiguration lymphaticovenous anastomoses. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):935-943.

25. Yamamoto T, Narushima M, Kikuchi K, et al. Lambda-shaped anastomosis with intravascular stenting method for safe and effective lymphaticovenular anastomosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(5):1987-1992.

26. Yamamoto T, Yoshimatsu H, Narushima M, et al. Sequential anastomosis for lymphatic supermicrosurgery: multiple lymphaticovenular anastomoses on 1 venule. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;73(1):46-49.

27. Boccardo F, Fulcheri E, Villa G, et al. Lymphatic microsurgery to treat lymphedema: techniques and indications for better results. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;71(2):191-195.

28. Maegawa J, Mikami T, Yamamoto Y, Hirotomi K, Kobayashi S. Lymphaticovenous shunt for the treatment of chylous reflux by subcutaneous vein grafts with valves between megalymphatics and the great saphenous vein: a case report. Microsurgery. 2010;30(7):553-556.

29. Chang DW, Suami H, Skoracki R. A prospective analysis of 100 consecutive lymphovenous bypass cases for treatment of extremity lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(5):1305-1314.

30. Becker C, Piquilloud G, Lee BB. Lymph nodes transplantation. In: Lee BB, Rockson SG, eds. Lymphedema: A Concise Compendium of Theory and Practice. 2nd Ed. Springer International Publishing AG 2011; 2018:369-380.

31. Akita S, Mitsukawa N, Kuriyama M, et al. Comparison of vascularized supraclavicular lymph node transfer and lymphaticovenular anastomosis for advanced stage lower extremity lymphedema. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;74(5):573-579.

32. Becker C, Hidden G. Transfer of free lymphatic flaps. Microsurgery and anatomical study [article in French]. J Mal Vasc. 1988;13(2):119-122.

33. Saaristo AM, Niemi TS, Viitanen TP, Tervala TV, Hartiala P, Suominen EA. Microvascular breast reconstruction and lymph node transfer for postmastectomy lymphedema patients. Ann Surg. 2012;255(3):468-473.

34. Lee BB, Laredo J, Neville R. Current status of lymphatic reconstructive surgery for chronic lymphedema: it is still an uphill battle! Int J Angiol. 2011;20(2):73-79.

35. Gloviczki P. Principles of surgical treatment of chronic lymphoedema. Int Angiol. 1999;18(1):42-46.

36. Becker C, Hidden G, Godart S, Maurage H, Pecking A. Free lymphatic transplantation. Eur J Lymphol. 1991;6(2):75-80.

37. Becker C, Hidden G, Pecking A, et al. Transplantation of lymph nodes: an alternative method for the treatment of lymphedema. Progress in Lymphology. 1990;XI:487-493.

38. Lee BB, Kim YW, Seo JM, et al. Current concepts in lymphatic malformation (LM). Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2005;39(1):67- 81.

39. Lee BB. Lymphedema-angiodysplasia syndrome: a prodigal form of lymphatic malformation. Phlebolymphology. 2005;47:324-332.

40. Guidelines 6.4.0. on medical and physical therapy. In: Gloviczki P, ed. Handbook of Venous Disorders: Guidelines of the American Venous Forum. 3rd Edition. London, UK: Hodder Arnold; 2009:663.

41. Lee BB, Laredo J, Neville R. Current dilemma with controversy. In: Lee BB, Bergan J, Rockson SG, eds. Lymphedema: A Concise Compendium of Theory and Practice. 1st edition. London, UK: Springer-Verlag; 2011:381-386.

42. Babb RR, Spittell JA Jr, Martin WJ, Schirger A. Prophylaxis of recurrent lymphangitis complicating lymphedema. JAMA. 1966;195(10):871-873.

43. Campisi C, Boccardo F, Campisi CC, Ryan M. Reconstructive microsurgery for lymphedema: while the early bird catches the worm, the late riser still benefits. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(3):506-507.

44. Lee BB, Antignani PL, Baroncelli TA, et al. IUA-ISVI consensus for diagnosis guideline of chronic lymphedema of the limbs. Int Angiol. 2015;34(4):311-332.

45. Lee BB, Villavicencio JL: Primary lymphedema and lymphatic malformation: are they the two sides of the same coin? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39(5):646-653.

46. Lee BB, Laredo J. Pathophysiology of primary lymphedema. In: Neligan PC, Piller NB, Masia J, eds. Complete Medical and Surgical Management. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2016:177-188.

47. Lee BB, Laredo J, Neville R: Primary lymphedema as a truncular lymphatic malformation. In: Lee BB, Bergan J, Rockson SG, eds. Lymphedema: A Concise Compendium of Theory and Practice. 1st edition. London, UK: Springer-Verlag; 2011:419-426.

48. Papendieck CM. Lymphangiomatosis and dermoepidermal disturbances of lymphangioadenodysplasias. Lymphology. 2002;35:478-485.

49. Campisi C, Boccardo F. Microsurgical techniques for lymphedema treatment: derivative lymphatic-venous microsurgery. World J Surg. 2004;28(6):609-613.

50. Papendieck CM. Lymphatic dysplasia in pediatrics. A new classification. Int Angiol. 1999;18(1):6-9.

51. Torrisi JS, Joseph WJ, Ghanta S, et al. Lymphaticovenous bypass decreases pathologic skin changes in upper extremity breast cancer-related lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol. 2015;13(1):46-53.

52. Chang DW, Suami H, Skoracki R. A prospective analysis of 100 consecutive lymphovenous bypass cases for treatment of extremity lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(5):1305-1314.

53. Yamamoto T, Yoshimatsu H, Yamamoto N, Yokoyama A, Numahata T, Koshima I. Multisite lymphaticovenular anastomosis using vein graft for uterine cancerrelated lymphedema after pelvic lymphadenectomy. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49(7):195-200.

54. Maegawa J, Mikami T, Yamamoto Y, Hirotomi K, Kobayashi S. Lymphaticovenous shunt for the treatment of chylous reflux by subcutaneous vein grafts with valves between megalymphatics and the great saphenous vein: a case report. Microsurgery. 2010;30(7):553-556.

55. Noel AA, Gloviczki P, Bender CE, Whitley D, Stanson AW, Deschamps C. Treatment of symptomatic primary chylous disorders. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34(5):785-791.

56. Basta MN, Gao LL, Wu LC. Operative treatment of peripheral lymphedema: a systematic meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of lymphovenous microsurgery and tissue transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(4):905-913.

57. Baumeister RGH. Lymphedema: surgical treatment. In: Cronenwett JL, Johnston KW, eds. Rutherfod’s Vascular Surgery. 8th edition. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Sauders; 2014:1028-1042.

58. Silva AK, Chang DW. Vascularized lymph node transfer and lymphovenous bypass: novel treatment strategies for symptomatic lymphedema. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113(8):932-939.

59. Baumeister RG, Frick A. Die mikrochirurgische Lymphgefäßtransplantation. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2003;35(4):202- 209.

60. Weiss M, Baumeister RGH, Hahn K. Posttherapeutic lymphedema: scintigraphy before and after autologous lymph vessel transplantation: 8 years of long-term follow-up. Clin Nucl Med. 2002;27(11):788-792.

61. Raju A, Chang DW. Vascularized lymph node transfer for treatment of lymphedema: a comprehensive literature review. Ann Surg. 2015;261(5):1013- 1023.

62. Becker C, Assouad J, Riquet M, Hidden G. Postmastectomy lymphedema: longterm results following microsurgical lymph node transplantation. Ann Surg. 2006;243(5):313-315.

63. Patel KM, Lin CY, Cheng MH. A prospective evaluation of lymphedemaspecific quality-of-life outcomes following vascularized lymph node transfer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(7):2424-2430.

64. International Society of Lymphology. The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2013 consensus document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology. 2013;46:1-11.

65. Huang JJ, Gardenier JC, Hespe GE, et al. Lymph node transplantation decreases swelling and restores immune responses in a transgenic model of lymphedema. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168259.

66. Lähteenvuo M, Honkonen K, Tervala T, et al. Growth factor therapy and autologous lymph node transfer in lymphedema. Circulation. 2011;123(6):613-620.

67. Brorson H. Liposuction in lymphedema treatment. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2016;32:56-65.

68. Lee BB, Kim YW, Kim DI, Hwang JH, Laredo J, Neville R. Supplemental surgical treatment to end stage (stage IV-V) of chronic lymphedema. Int Angiol. 2008;27(5):389-395.

69. Kim DI, Lee BB, Huh S, Lee SJ, Hwang JH, Kim YI. Excision of subcutaneous tissue and deep muscle fascia for advanced lymphedema. Lymphology. 1998;31(4):190-194.

70. Huh SH, Kim DI, Hwang JH, Lee BB. Excisional surgery in chronic advanced lymphedema. Surg Today. 2003;34:434- 435.

71. Rockson SG, Miller LT, Senie R, et al. American Cancer Society Lymphedema Workshop. Workgroup III: diagnosis and management of lymphedema. Cancer. 1998;83(12):2882-2885.

72. Auchincloss H. New operation for elephantiasis. PR J Public Health Trop Med. 1930;6:149-152.

73. Homans J. The treatment of elephantiasis of the legs – a preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1936;215(24):1099-1103.

74. Brorson H, Svensson H. Liposuction combined with controlled compression therapy reduces arm lymphedema more effectively than controlled compression therapy alone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(4):1058-1067.

75. Dellon AL, Hoopes JE. The Charles procedure for primary lymphedema. Long-term clinical results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;60:589-595.

76. Sistrunk WE. Further experiences with the Kondoléon operation for elephantiasis. JAMA. 1918;71(10):800-806.

77. Kinmonth JB, Patrick JH, Chilvers AS. Comments on operations for lower limb lymphedema. Lymphology. 1975;8(2):56- 61.

78. Lee BB, Laredo J, Neville R. Contemporary indication and controversy on excisional surgery. In: Lee BB, Bergan J, Rockson SG, eds. Lymphedema: A Concise Compendium of Theory and Practice. 1st edition. London, UK: Springer-Verlag; 2011:403-408.

79. Brorson H, Svensson H, Norrgren K, Thorsson O. Liposuction reduces arm lymphedema without significantly altering the already impaired lymph transport. Lymphology. 1998;31(4):156-172.

80. Brorson H. From lymph to fat: complete reduction of lymphoedema. Phlebology. 2010;25(suppl 1):52-63.

81. Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Karlsson MK. Breast cancer-related chronic arm lymphedema is associated with excess adipose and muscle tissue. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7(1):3-10.

82. Brorson H. Liposuction in arm lymphedema treatment. Scand J Surg. 2003;92(4):287-295.

83. Lee BB, Laredo J, Lee TS, Huh S, Neville R. Terminology and classification of congenital vascular malformations. Phlebology. 2007;22(6):249-252.

84. Lee BB, Laredo J, Kim YW, Neville R. Congenital vascular malformations: general treatment principles. Phlebology. 2007;22(6):258-263.

85. Lee BB. All congenital vascular malformations should belong to one of two types: “truncular” or “extratruncular”, as different as apples and oranges! Phlebol Rev. 2015;23(1):1-3.

86. Lee BB, Laredo J, Neville R, Mattassi R. Primary lymphedema and Klippel- Trenaunay syndrome. In: Lee BB, Bergan J, Rockson SG, eds. Lymphedema: A Concise Compendium of Theory and Practice. 1st edition. London, UK: Springer-Verlag; 2011: 427-436.

87. Frick A, Hoffmann JN, Baumeister RG, Putz R. Liposuction technique and lymphatic lesions in lower legs: anatomic study to reduce risks. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103(7):1868-1873.

88. Brorson H, Ohlin K, Olsson G, Långström G, Wiklund I, Svensson H. Quality of life following liposuction and conservative treatment of arm lymphedema. Lymphology. 2006;39(1):8-25.

89. Hoffner M, Bagheri S, Hansson E, Manjer J, Troëng T, Brorson H. SF-36 shows increased quality of life following complete reduction of postmastectomy lymphedema with liposuction. Lymphat Res Biol. 2017;15(1):87-98.

90. Lee D, Piller N, Hoffner M, Manjer J, Brorson H. Liposuction of postmastectomy arm lymphedema decreases the incidence of erysipelas. Lymphology. 2016;49(2):85-92.