Results of the DECIDE survey: appraisal of the predictive value for chronic venous disease of a symptom checklist

Françoise PITSCH

ABSTRACT

Objectives: The main objective of the DECIDE study was to evaluate the predictive value of a symptom checklist for chronic venous disease (CVD) in patients seen by general practitioners. The secondary objectives were to assess the relationship between the checklist data and the patient’s quality of life evaluated using the Chronic Venous Insufficiency Questionnaire (CIVIQ), and to monitor the medium-term evolution of this relationship amongst patients prescribed a venoactive drug.

Method: Consecutive patients in general practice presenting symptoms that could be ascribed to CVD were included. Patients with an advanced form of CVD, ie, skin changes and a history of venous ulcers, were excluded.

Results: A total of 13131 patients were included by 1323 general practitioners, whose acceptance of the symptom checklist was good, since the completion rate was high. Of the 2104 patients referred to venous specialists, 2080 were confirmed as suffering from CVD. The correlation between a positive diagnosis of CVD and positive answer to the symptom checklist was 98.9% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 98.3%-99.3%), indicating that the symptom checklist is of predictive value for CVD. The CIVIQ-20 was of discriminatory value since there was a 12-point difference between patients with and without CVD (64.4 ±17.9 vs 76.2±16.4, respectively; P<0.001). Of 9953 patients followed up for an average of 63 days, 88.7% received MPFF at a dose of 500 mg, 5.1% received another venoactive drug, and 3.5% were left untreated. After the 63-day follow-up, a significant decrease in CVD symptoms was observed in all patients treated with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg. Amongst the 7103 patients to whom the CIVIQ-20 was readministered, a significantly greater improvement in quality of life was seen in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg group compared with the other treatment groups. Conclusion: This symptom checklist may be used as a predictive tool for CVD in general practice. Data from the present survey show that CVD has a negative impact on patients’ quality of life. Finally, a 63-day treatment with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg rapidly alleviated symptoms of CVD and significantly improved the quality of life of CVD patients.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic venous disease (CVD) of the lower limbs is defined as “morphological and functional abnormalities of the venous system of long duration manifest either by symptoms and/or signs indicating the need for investigation and/or care”,1 while “chronic venous insufficiency” is the term reserved for more severe forms of the disease (from C3 to C6 of the CEAP classification).1 Varicose veins are one of the most common manifestations of CVD.2

Symptoms related to CVD include tingling, aching, burning, pain, muscle cramps, sensation of swelling, of throbbing, of heaviness, itching, restless legs, leg tiredness, and fatigue.1 CVD can lead to acute (rupture of varicose veins, venous thrombosis) or chronic complications (dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, chronic leg ulcers).3,4

The impact of CVD is substantial.5-9 Both symptoms and visible varicose veins, even in the absence of complications, lead many patients to seek medical advice. Although uncomplicated varicose veins have little functional impact, they nonetheless affect quality of life, mainly in social terms.2,10 At the other end of the spectrum, the most serious manifestations of CVD, such as venous leg ulcers, are a major medical problem. Venous ulcers have a poor prognosis, and delayed healing and recurrences are very frequent.11-13

Apart from general and physical measures,2,14 venoactive drugs are of proven efficacy in alleviating symptoms. A recent review of available clinical data15 has made it possible to assign a high level rating (grade 1B according to Guyatt’s recommendations)16 to clinical evidence of symptom relief for a few active substances, such as MPFF at a dose of 500 mg.17-20 Apart from advanced stages of the disease, it is often difficult to recognize CVD, for two main reasons: the symptoms are not related solely to CVD1,2,21 and are notalways associated with signs in patients designated C0 in the CEAP classification, who account for up to 15% of the general population. But, the venous nature of symptoms is suggested by their worsening during the day, after a prolonged period of standing or sitting, on exposure to heat, and during the premenstrual period in women, and their improvement in response to cold, lower limb elevation, and exercise.

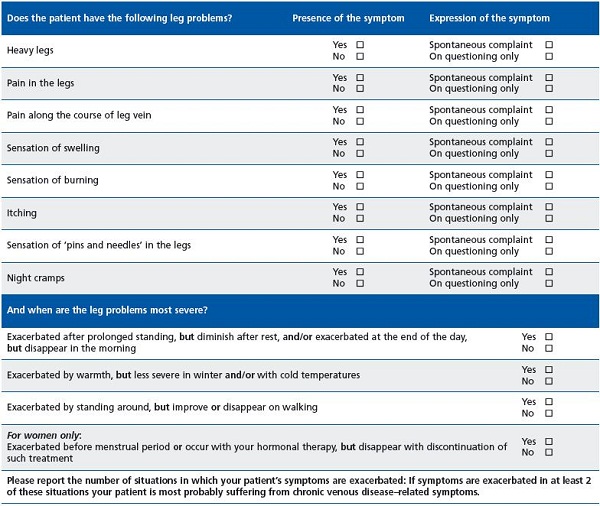

To help physicians identify the venous origin of CVD, a symptom checklist was designed (Table I). It contains the most commonly reported symptoms of CVD and allows assessment of their worsening and/or improvement in 4 cases. If such a change is observed for at least two of the cases, the venous origin of these symptoms is considered highly likely.

The checklist has not yet been evaluated in a prospective study to assess its utility in everyday medical practice. Evaluation of this utility is based primarily on confirmation of its positive predictive value, and on assessment of its ability to identify patients in whom symptoms have a high impact and for whom an active therapeutic strategy would be the most beneficial.

A non-interventional evaluation of the checklist was conducted in a population of patients seen by general practitioners. The checklist was used if the general practitioner decided to advise the patient to start treatment with a venoactive drug because of symptoms suggestive of CVD. The Chronic Venous Insufficiency Questionnaire (CIVIQ) was used to assess the impact of CVD on the patient’s quality of life. It consists of 20 questions designed to assess four dimensions (physical, psychological, social, and pain) and has been widely validated in various stages of CVD.17,22-25 This questionnaire is sensitive in the short and medium term to changes in symptoms that occur spontaneously or following initiation of treatment.23,24

METHODS

Objectives The primary objective of this prospective, noninterventional survey was to evaluate the predictive value of a symptom checklist for CVD in patients seen by general practitioners. The secondary objectives were to assess the relationship between the checklist data and the patient’s quality of life evaluated using the CIVIQ, and to monitor the medium-term evolution of this relationship in patients prescribed a venoactive drug.

Patients

Adult subjects, with no upper age limit, seen in general medical practice and presenting with symptoms suggestive of CVD, confirmed by use of a symptom checklist. On the day of the visit these patients were not receiving medical therapy of CVD, and did not present with skin changes or a history of venous ulcers. The CEAP international classification, with which general practitioners too often are still not very familiar, was not used in this study, but “purists” can note that all patients were rated Cos, C1s, C2s, or C3s.

Methodology

Starting with the date when the survey was set up, in a given medical practice, the first ten patients seen successively and who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled. Treatments of venous disease initiated were recorded. In particular, the general practitioner noted if he/she referred the patient to a specialist for an opinion on venous disease. The patient was informed of the objectives of the survey and then completed a CIVIQ. If the patient was seen again at a follow-up visit 3-6 months later, the general practitioner used the symptom checklist to assess any changes in symptoms. The patient’s compliance with any treatment of CVD was assessed and another CIVIQ was filled out. If a specialist’s opinion was requested, any laboratory findings were reported along with the specialist’s conclusions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with l SPSS 13.0 software.

The total population was classified into several subgroups, taking into account sex, age category and type of venoactive treatment prescribed (MPFF at a dose of 500 mg or another).

The positive predictive value of the checklist was calculated based on the subpopulation of patients with available specialized laboratory data.

Categorical variables were compared between the different subgroups using a chi-square test. Univariate or multivariate analyses were used for quantitative variables.

Data are presented as means ± the standard error (SEM) or as a percentage. 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using a normal approximation for quantitative variables and the Clopper-Pearson method for nominal or ordinal variables.

For quality of life results, the global index score of CIVIQ was used, and for convenient reading of results, a score of 0 was considered the worst possible, while 100 was the best possible.

Ethical and regulatory context

In this non-interventional survey, no data obtained directly or indirectly from visits was collected.

The essential documents of this survey were submitted for approval to the National Board of the French General Medical Council (Conseil National de l’Ordre des Médecins) before it was initiated.

Patients concerned received an information leaflet informing them that their doctor was participating in a national survey and that their personal medical data, from which their names had been removed, would be computer processed, and that they were entirely free to agree to participate in the survey or not.

RESULTS

Population enrolled

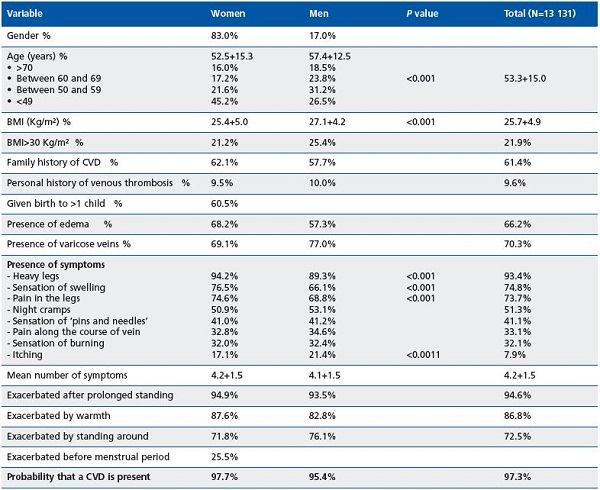

A total of 1323 general practitioners throughout metropolitan France enrolled 13 131 patients between June 2008 and July 2009. This predominantly female (83.0% women, 60.5% of whom were multiparous) population (Table II) had a mean age of 53.3 ± 15.0 years, the women being younger than the men on average (45% of women were under 50 years of age vs 26.5% of the men). Mean BMI was 25.7 ± 4.9 kg/m2. A BMI >30 kg/m2 was noted in 22% of patients, most often men. In 61.4% of cases the patient’s mother or father or both had a history of CVD, 9.6% of patients had a history of phlebitis, and 69.6% of patients reported a sedentary lifestyle.

In the physical examination, telangiectases and varicose veins were observed in 70.3% of patients, most often men. Conversely, edema was more common in women (68.2% vs 57.3%).

Use of the checklist for detection of CVD

Use of the checklist for detection of CVD in this population never posed a problem in terms of filling out the questionnaire in routine visits. Of the eight symptoms routinely sought, sensation of heaviness in the legs, swollen legs, and painful legs were by far the most prevalent in both men and women (greater than or equal to 70% in patients reporting these symptoms), but with a higher incidence in women (Table II). These three symptoms were spontaneously reported by patients in 56.7%, 41.8%, and 38.9% of cases, respectively. Pruritus was the symptom least frequently reported (21.4% of men vs 17.1% of women). Patients had 4.2 ± 1.5 symptoms on average, with no clinically relevant difference according to sex. However, the number of symptoms rose significantly with age, from 3.8 ± 1.5 in patients under 40 years of age to 4.4 ± 1.5 in patients aged over 70 (P<0.001).

Worsening was almost always observed (94.6% of cases) in patients in the standing position, with an improvement or disappearance of symptoms at rest. The effect of warmth and of standing was also dominant, while an effect associated with menstruation was only observed in 25% of women.

In summary, based on the checklist data, CVD was considered likely in this population.

Impact of symptoms on quality of life

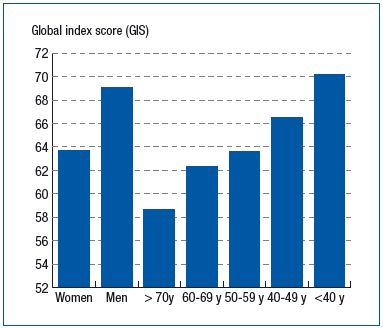

A CIVIQ was filled out at visits by 9848 patients (75.0% of those included). The most altered dimension in the CIVIQ was pain (50.7% of men and 58.0% of women had a score of 50 or lower), while the psychological dimension was the least altered. An overall score of 50 or lower, indicating a major alteration in quality of life, was observed in 15.6% of men and 23.5% of women. Overall, total CIVIQ score and that of its dimensions, with age being constant, were very significantly lower in women (Figure 1). Except for pain, whose mean score was stable, these scores decreased with increasing age, regardless of sex (Figure 1).

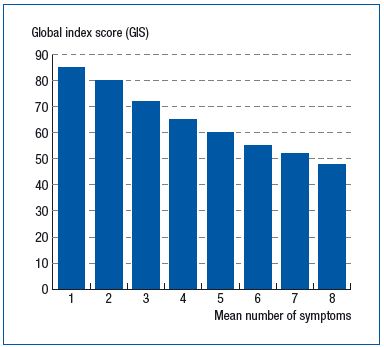

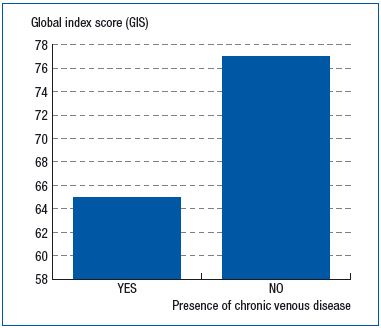

This score was also positively and significantly correlated with the number of symptoms in the checklist, decreasing from 85.0 ± 13.5 when a single symptom was observed to 53.8 ± 17.9 (r=0.462; P<0.001) when all eight symptoms were reported. (Figure 2). The CIVIQ-20 was of discriminatory value since there was a 12-point difference between patients with and without CVD (64.4 ±17.9 vs 76.2±16.4, respectively; P<0.001) (Figure 3).

Specialist’s opinion requested on treatments

The opinion of a venous specialist or a vascular specialist was requested for 2475 patients (18.8% of the total population), mainly regarding treatment in 56.2% of them. This population was characterized by a higher mean number of visits (4.6 ± 1.5 vs 4.1 ± 1.5 in the population for whom no opinion was requested; P<0.001) and a lower quality of life (with a global CIVIQ score of 64 on average).

At the end of the first visit, MPFF at a dose of 500 mg was prescribed in 90% of patients, another type of venoactive drug in 8%, and no treatment in 2%.

symptoms.

treatment with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg.

At the end of the first visit, MPFF at a dose of 500 mg was prescribed in 90% of patients, another type of venoactive drug in 8%, and no treatment in 2%.

Positive predictive value of the symptom checklist

Of 2475 patients for whom a specialist’s opinion was requested, 2155 were seen again at a follow-up visit. In 85% of these patients, the results of duplex ultrasound scanning were available.

Superficial venous disease was seen in 48.8% of patients and, in terms of pathophysiology, reflux was noted in 54% of these patients, 42% of whom were treated by the specialist (sclerotherapy in 54% of cases).

In 2104 patients who likely have CVD based on the symptom checklist, confirmation or not of CVD was clearly documented. CVD was confirmed by a specialist in 2080 cases, and the positive predictive value of the symptom checklist was 98.9% (95% CI: 98.3%-99.3%).

Patients seen again and compliance with therapy

A total of 9954 patients were seen again at a follow-up visit. Median follow-up was 63 days; 8834 (88.7%) patients were receiving MPFF at a dose of 500 mg, 511 (5,1%) were treated with another venoactive drug, and 260 (2.6%) were not receiving any type of treatment. In 349 cases (3.5%), there was no record of whether or not a venoactive drug was used.

In the general practitioner’s opinion, compliance with the recommended venoactive drug therapy was very good in 62.7% of cases (63.6% in patients receiving MPFF at a dose of 500 mg and 49.6% in those on another venoactive drug), acceptable in 33.8%, and mediocre or poor in 3.5% of patients.

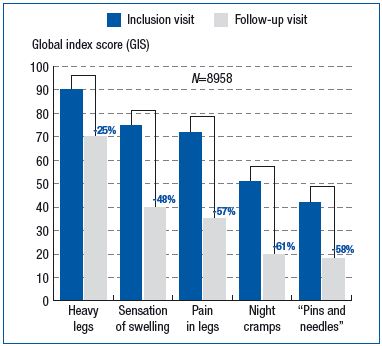

Symptoms at the follow-up visit

Prevalence of all eight symptoms on the checklist decreased markedly. In patients receiving MPFF at a dose of 500 mg, prevalence decreased by 26% for sensation of heaviness in the legs, 59% for sensation of swelling, and 62% for painful legs (Figure 4). The number of symptoms present at the follow-up visit per patient treated with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg decreased by 2.1 ± 1.5 on average, vs baseline visit (P<0.001). This decrease was significantly lower in patients treated with another type of venoactive drug (-1.7 ± 1.5; P<0.001).

Based on their overall impression scored on an 8-point rating scale, the general practitioners reported good or very good improvement in symptoms in 66.3% of patients who received MPFF at a dose of 500 mg vs 38.7% in those receiving another type of venoactive drug (P<0.001).

Quality of life at the follow-up visit

A CIVIQ was filled out for 7103 patients at the baseline visit and during monitoring. All dimensions of the CIVIQ improved very significantly at the second evaluation, the greatest improvement being in pain. Overall quality of life score increased by 15.8 ± 12.5 in patients treated with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg and by 10.3 ± 10.4 in those treated with another venoactive drug (P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this observational survey was to evaluate whether a symptom checklist would help non-specialist physicians diagnose CVD when suggestive symptoms are present. This checklist incorporates the eight most commonly reported symptoms in CVD, and, in particular, the evaluation of four situations in which these symptoms are worsened or improved depending on the presence or absence of the triggering factor (prolonged standing, exposure to warmth, standing about, and the pre-menstrual period in women). When at least two of these situations have an effect, CVD can be considered likely. Thus, it is not the symptoms themselves, whatever their severity, which guide the diagnosis, but solely the change in their severity in the situations evaluated. In at least two cases, both worsening and relief must be noted, depending on whether or not the situation occurs.

Very few instruments of this type, with a purely diagnostic purpose, have been developed. In this regard, the efficacy of routine screening is undergoing evaluation. Such screening programs are conducted by specialized centers and include noninvasive investigations. Although the first results are promising, these programs cannot be applied to conditions of general medical practice where the diagnosis will be based mainly on the clinical interview and a physical examination of the patient.

A checklist relatively similar to the one used in this study was developed by Carpentier et al,26 who also considered above all the effect of triggering factors. Based on a 54- item questionnaire, these authors selected 6 items which when combined showed very good sensitivity and specificity. But this questionnaire requires cautious interpretation and may not be suitable for routine visits in general practice. This is why the checklist used in our study was developed and designed to enable rapid completion and immediate use in guiding in the diagnosis.

The results of this survey in a very large sample of general practitioners clearly demonstrate that the objective of a simple-to-use checklist was achieved. The likelihood of a patient presenting with CVD when the checklist results were positive (positive predictive value) was very high (99%) in a highly diversified population. However, this value must be interpreted with caution, insofar as diagnostic confirmation was requested mainly in those patients who tended to have many symptoms and therefore were at high risk of actually presenting with CVD. Nevertheless, in the case of a positive test result, overall the patients concerned had more symptoms and a lower quality of life, which is evidence of the utility of this type of instrument in everyday practice.

In summary, this survey demonstrates that patients in whom a general practitioner must decide whether to initiate treatment with a venoactive agent are those in whom there is an impact, sometimes severe, of CVD. Assessed by means of the CIVIQ, this impact relates particularly to pain, as more than half of the patients have a score of 50 or more (100 being the worst), which is indicative of a major impairment of quality of life. This high score is found whatever the patient’s sex and age. However, in spite of this reduced quality of life, a specialist’s opinion is sought in very few cases (19%), even though venous investigations would undoubtedly be useful in assessing the hemodynamic impact, locating the lesions, and initiating the most effective treatment.

Nevertheless, initiation of a venoactive treatment, in particular with a drug of proven efficacy such as MPFF at a dose of 500 mg, alleviates symptoms quickly and improves quality of life. This effect is that much greater when compliance with therapy is good. This improvement is also better than that observed with other venoactive drugs not recommended as grade 1, an observation which supports the recommendations of consensus conferences in their classification of venoactive drugs. However, insofar as this study was not randomized, this observation should be interpreted cautiously. In conclusion, this survey demonstrates that a simple symptom checklist can be used in general medical practice to simplify the decisions of general practitioners regarding CVD. The aim was not to validate this checklist in the detection of CVD, but the survey nevertheless confirms its high positive predictive value and shows that it deserves to be used by vascular specialists.

REFERENCES

1. Eklof B, Perrin M, Delis KT et al. Updated terminology of chronic venous disorders: The VEIN Term transatlantic interdisciplinary consensus document. J Vasc Surg 2009;49:498-501.

2. Bergan JJ, et al., Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med, 2006. 355(5):. 488-98.

3. Nicolaides AN, Chronic venous disease and the leukocyte-endothelium interaction: from symptoms to ulceration. Angiology, 2005. 56 Suppl 1: S11-9.

4. Coleridge-Smith P. The causes of skin damage and leg ulceration in chronic venous disease. Int J Low Extrem Wounds, 2006. 5(3): 160-8.

5. Tsai S, et al., Severe chronic venous insufficiency: magnitude of the problem and consequences. Ann Vasc Surg, 2005. 19(5): 705-11.

6. Abbade LP and S. Lastoria, Venous ulcer: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol, 2005. 44(6): 449-56.

7. Simka M and Majewski E, The social and economic burden of venous leg ulcers: focus on the role of micronized purified flavonoid fraction adjuvant therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol, 2003. 4(8): 573-81.

8. Kurz X, et al., Chronic venous disorders of the leg: epidemiology,outcomes, diagnosis and management. Summary of an evidence-based report of the VEINES task force. Venous Insufficiency Epidemiologic and Economic Studies. Int Angiol, 1999. 18(2): 83-102.

9. Van den Oever R, et al., Socio-economic impact of chronic venous insufficiency. An underestimated public health problem. Int Angiol, 1998. 17(3): 161-7.

10. Kahn SR, et al., Relationship between clinical classification of chronic venous disease and patient-reported quality of life: results from an international cohort study. J Vasc Surg, 2004. 39(4): 823-8.

11. Margolis DJ, J.A. Berlin, and B.L. Strom, Which venous leg ulcers will heal with limb compression bandages? Am J Med, 2000. 109(1): 15-9.

12. Margolis DJ, J.A. Berlin, and B.L. Strom, Risk factors associated with the failure of a venous leg ulcer to heal. Arch Dermatol, 1999. 135(8): 920-6.

13. Callam MJ, et al., Chronic ulcer of the leg: clinical history. Br Med J, 1987. 294(6584): 1389-91.

14. Nicolaides AN, Investigation of chronic venous insufficiency: A consensus statement (France, March 5-9, 1997). Circulation, 2000. 102(20):. E126-63.

15. Perrin M, Ramelet AA. Pharmacological Treatment Of Primary Chronic Venous Disease: Rationale, Results, And Unanswered Questions. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011; 41: 117- 125.

16. Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines. Chest 2006; 129: 174-81.

17. Coleridge-Smith P. MPFF at a dose of 500 mg and venous leg ulcer: new results from a meta-analysis. Angiology, 2005. 56 Suppl 1: S33-9.

18. Ramelet AA, MPFF at a dose of 500 mg: symptoms and edema clinical update. Angiology, 2005. 56 Suppl 1: S25-32.

19. Katsenis K, Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF): a review of its pharmacological effects, therapeutic efficacy and benefits in the management of chronic venous insufficiency. Curr Vasc Pharmacol, 2005. 3(1): 1-9.

20. Bergan JJ, Chronic venous insufficiency and the therapeutic effects of MPFF at a dose of 500 mg. Angiology, 2005. 56 Suppl 1: S21-4.

21. Chiesa R, et al., Chronic venous disorders: correlation between visible signs, symptoms, and presence of functional disease. J Vasc Surg, 2007. 46(2):322-30.

22. Launois R, Reboul-Marty J, and B. Henry, Construction and validation of a quality of life questionnaire in chronic lower limb venous insufficiency (CIVIQ). Qual Life Res, 1996. 5(6): 539-54.

23. Jantet G, Chronic venous insufficiency: worldwide results of the RELIEF study. Reflux assEssment and quaLity of lIfe improvEment with micronized Flavonoids. Angiology, 2002. 53(3): p. 245-56.

24. Guex JJ, et al., Chronic venous disease: health status of a population and care impact on this health status through quality of life questionnaires. Int Angiol, 2005. 24(3): p. 258-64.

25. McLafferty RB, et al., Results of the national pilot screening program for venous disease by the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg, 2007. 45(1): p. 142-148.

26. Carpentier PH, et al., Ascribing leg symptoms to chronic venous disorders: the construction of a diagnostic score. J Vasc Surg, 2007. 46(5): p. 991-6.