Results from detection surveys on chronic venous disease in Eastern Europe

ervier Interntational

Suresnes, France

INTRODUCTION

Chronic venous disease (CVD) is common among general populations.1 Both general practitioners and specialist doctors have to deal with this pathology, which is often mild in presentation but potentially progressive. Despite this, it is acknowledged that CVD is usually overlooked both by doctors who underdiagnose the condition and by patients themselves who rarely consult spontaneously for venous leg problems except in the advanced stages.2 As a consequence, CVD is undertreated, particularly in the early stages. CVD may be associated with a wide range of lower limb symptoms, which may be present from the outset even before any visible signs of CVD have been identified. Therefore, patients’ queries about leg symptoms and their variability with position might be the best way to detect CVD and the first step of a more in-depth investigation.2

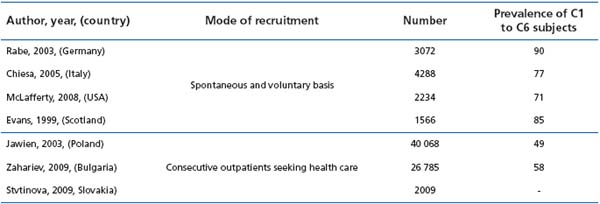

Recent population-based surveys using the clinical, etiological, anatomical, pathophysiological (CEAP) classification report prevalence rates of CVD of 49% in Poland,3 71% in the US,4 77% in Italy,5 85% in Scotland,6 and 90% in Germany.7 Most epidemiological surveys had until recently been conducted in Western industrialized countries and few in the Eastern part of Europe. The aim of the present review was to collect data from this part of the world, ie, from Bulgaria,2 Poland,3 and Slovakia.8

METHOD

All 3 surveys were multicenter, cross-sectional surveys conducted in primary care centers in which consecutive patients seeking medical help, regardless of cause, were enrolled. They were performed in 2006 in Bulgaria, 2002 in Poland, and 2008 in Slovakia. A total of 26 785, 40 068 and 2009 subjects, respectively, in Bulgaria, Poland, and Slovakia were queried about possible venous leg problems. Clinical interviews were performed according to a questionnaire especially designed for this purpose which reported patients’ demographic data, complaints suggestive of CVD and when they were more likely to occur, and the presence of visible signs like telangiectasias, varicose veins, edema, skin changes, and healed or active venous leg ulcer. In Slovakia, patients with skin changes and ulcers were not retained in the analysis. Physicians were required to assign patients to one of the CEAP classes by taking into account the highest descriptor.9

The Slovak questionnaire included a monitoring part since patients considered as suffering from CVD and requiring pharmacological treatment were treated with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg, 2 tablets per day for 3 months. Reduction of symptoms after a 3-month MPFF at a dose of 500 mg treatment was assessed and expressed in the percentage of patients without the symptom, whether or not patients were previously treated with another venoactive drug.

RESULTS

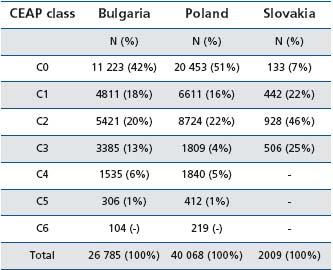

Tables I and II summarize the results in the 3 countries. Results in Slovakia were biased since patients with CVD complications (from C4 to C6) were not included.

Prevalence of C1 to C6 patients was 58% in Bulgaria and 49% in Poland. Prevalence of varicose veins was slightly higher than that of telangiectasias whatever the country (Table I), but the percentage of patients with edema varied greatly according to country, pointing to the difficulty of diagnosing this condition.

Table I: Distribution of patients by CEAP class in Bulgaria, Poland, and Slovakia (adapted from ref 2, 3, and 8 )

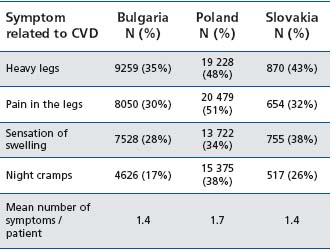

The symptoms most often encountered were ‘heavy legs’ and ‘pain in the legs’, while ‘night cramps’ are less reported (Table II).

Table I1: Presence of CVD-related symptoms in Bulgarian, Polish, and Slovak surveys. Each subject could present with one or more symptoms (adapted from ref 2, 3, and 8 )

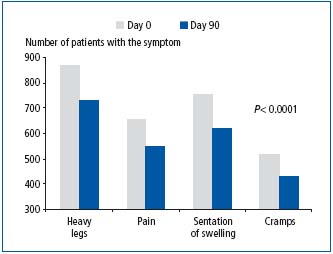

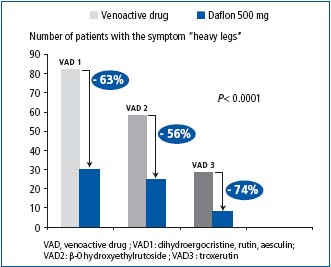

In Slovakia, where patients with CVD were given MPFF at a dose of 500 mg treatment, a significant improvement was found after 3 months for all symptoms (Figure 1). In the sub-groups of patients previously treated with another venoactive drug, a greater improvement in the most reported symptom in Slovakia, ie, ‘heavy legs’, was noted when patients were switched to the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Symptom reduction after 3-month treatment with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg (adapted from ref 8 )

Figure 2. Reduction of ‘heavy legs’ after 3-month treatment with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg in the sub-groups of patients previously treated with other drugs (adapted from ref 8 )

DISCUSSION

In the Bulgarian survey2 the prevalence of CVD (58% of subjects had CVD) was close to that of the Polish survey3 (49%), which had the same design, but far less than in former surveys,4-7 the design of which was based on voluntary participation (Table III). In these last studies, subjects with the disease were therefore more likely to participate. This was most probably the case also in the Slovakian survey, for which patients were given a drug treatment in addition to the interview.

CONCLUSION

This review provides further confirmation that detection programs like the Bulgarian and Polish ones are very useful in heightening awareness of the need for early identification of CVD patients. It might be that due to their mode of recruitment, these types of survey reflect reality better than previous studies.4-7

A 3-month MPFF at a dose of 500 mg treatment relieved symptoms in a substantial proportion of patients, and to a greater extent than did other drugs of different composition (_-0 hydroxyethylrutoside; dihydroergocristine or troxerutin).

Table III : Presence of C1 to C6 patients in the epidemiological surveys that have used the CEAP clinical classification

REFERENCES

1. Robertson L, Evans C, Fowkes FGR. Epidemiology of chronic venous disease. Phlebology. 2008;23:103-111.

2. Zahariev T, Anastassov V, Girov K, et al. Prevalence of primary chronic venous disease: the Bulgarian experience. Int Angiol. 2009;28:303-310.

3. Jawien A, Grzela T, Ochwat A. Prevalence of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) in men and women in Poland: multicenter cross-sectional study in 40 095 patients. Phlebology. 2003;18:110-122.

4. McLafferty RB, Passman MA, Caprini JA, et al. Increasing awareness about venous disease: The American Venous Forum expands the National Venous Screening Program. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(2):394-349.

5. Chiesa R, Marone EM, Limoni C, Volonte M, Schaefer E, Petrini O. Chronic venous insufficiency in Italy: the 24-cities cohort study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:422-429.

6. Evans CJ, Fowkes FGR, Ruckley CV, Lee AJ. Prevalence of varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency in men and women in the general population. Edinburgh Vein Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:149-153.

7. Rabe E, Pannier-Fischer F, Bromen K, et al. Bonner Venenstudie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Phlebologie. Phlebologie. 2003;32:1-14.

8. Stvtinova V. Chronic venous disease. The results of the DETECTOR program. Lekarske Listy. 2009:14.[in Czech]

9. Eklöf B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, et al. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:1248- 1252.