Randomized controlled trials in the treatments of varicose veins

Bo EKLÖF Helsingborg – Sweden

Michel PERRIN Vascular Surgery – Lyon, France

PART 1

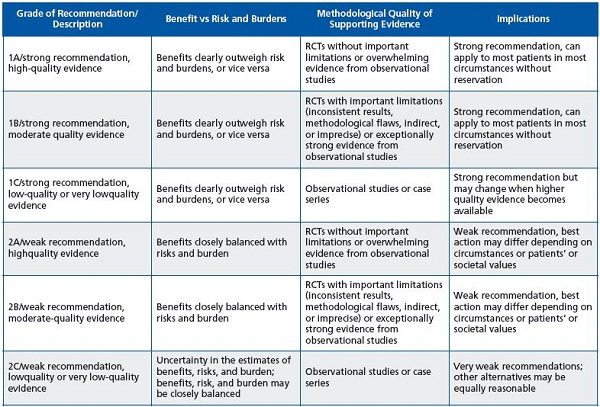

This is the first part of the 2 chapters about randomized controlled trials of treatments of varicose veins, either by open surgery or endovascular ablation. Although the American College of Chest Physicians Task Force took into account observational studies to establish the strength of recommendations according to the quality of the evidence,1 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) remain the most reliable source of evidence (Table I).1-6

We have therefore analyzed RCTs on treatment of varicose veins published since 1990 and have classified them by topic and added a brief comment. Nevertheless, as valuable as RCTs are, some have important limitations that are not always easy to identify7-10 and we may therefore have missed some of these in our comments. We successively consider and comment upon:

NB. Open surgery: saphenofemoral and/or saphenopopliteal junction ligation + stripping +/- perforator ligation+/- tributary phlebectomy

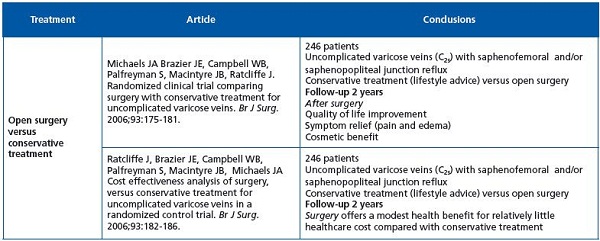

These two RCTs are the only ones comparing outcome at 2 years in C2s patients treated by classic surgery versus conservative treatment. Surgical patients reported better quality of life and significant benefits in symptomatic and anatomical measures, with modest reductions in healthcare costs. One may be surprised by paucity of RCTs on C2s patients, who represent the most important group in epidemiologic studies on varicose veins. The conclusions are interesting, but it should be noted that conservative treatment consisted only of lifestyle advice, without prescription of compression and/or venoactive drugs. This is surprising as we know that, at least in continental western Europe, many observational studies have demonstrated their effectiveness in C2s patients.

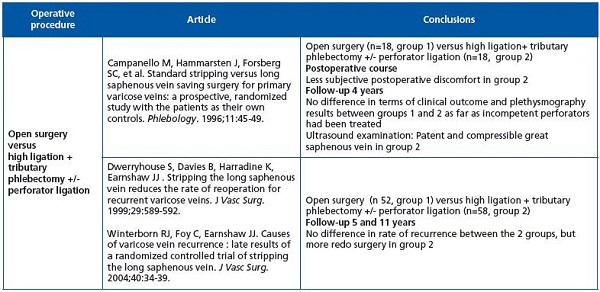

NB. Open surgery: high ligation + saphenous stripping +/- perforator ligation +/- tributary phlebectomy

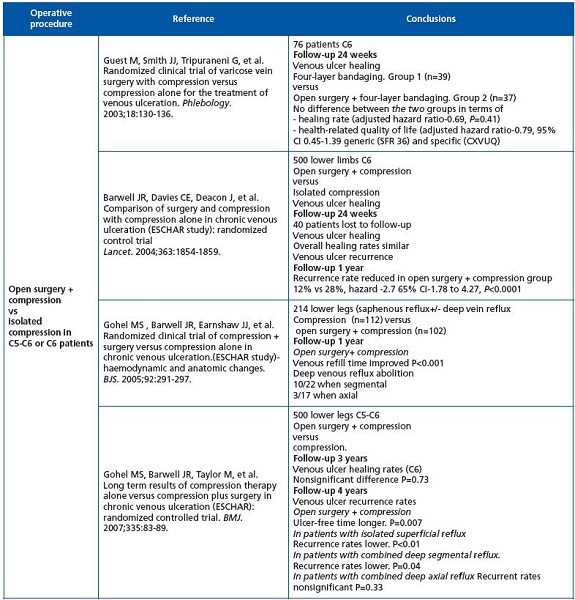

In Guest’s study as well as the ESCHAR study, operative treatment did not improve healing rate in C6 patients.

Concerning venous ulcer recurrence in the primary etiology, classic surgery plus compression gave better results than compression alone in patients without associated deep axial reflux. This does not mean that endovenous treatment, ie, chemical or thermal ablation, is less effective, but randomized, controlled trials are not yet available.

NB. Open surgery: high ligation + saphenous stripping +/- perforator ligation +/- tributary phlebectomy

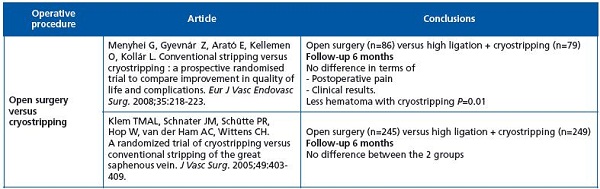

Although cryostripping is not at present frequently used, the 2 randomized controlled trials available were published 3 and 2 years ago, respectively. Postoperative hematoma is less frequent with cryostripping, but we know that with appropriate skill hematoma in classic stripping can easily be reduced.

NB. Open surgery: high ligation + saphenous stripping +/- perforator ligation +/- tributary phlebectomy

Preservation of the great saphenous vein (GSV) has been an issue since the 1950s. Fegan in Dublin was one of the pioneers when in 1950 he started compression sclerotherapy of incompetent perforators after which even large incompetent GSVs “normalized”. Michael Hume in Boston, a founder and past-president of the American Venous Forum, was also one of the founders of the informal “Society for the Preservation of the Main Trunk of the GSV” in the 1980s. Large in Australia reported in 1985 good clinical results after phlebectomy without stripping of the GSV, and Rose and Ahmad in Manchester (UK) in 1986 recommended excision of varicose veins leaving the GSV intact. Campanello and colleagues in Sweden in 1996 presented a randomized clinical trial on preservation of the GSV after high ligation, phlebectomy, and perforator ligation. It is interesting to note that the French alternatives for GSV preservation, CHIVA (1988; ambulatory conservative hemodynamic management of varicose veins) and ASVAL (2005; ambulatory selective varicose vein ablation under local anesthesia) were presented during this period. However, high ligation + tributary phlebectomy is not used today. The explanation lies probably in both the more precise information provided by duplex ultrasound investigation of the saphenofemoral junction (SFJ) and the outcome after endovenous ablation. Duplex ultrasound has shown in GSV incompetence that reflux at the SFJ is absent in many cases, and that the terminal valve is competent in about 50% of cases in the presence of SFJ reflux.

In thermal ablation as well as in chemical ablation, the termination of the SFJ remains open and this does not seem to negatively influence the results. Furthermore, high ligation is supposed to enhance recurrence related to neovascularization.

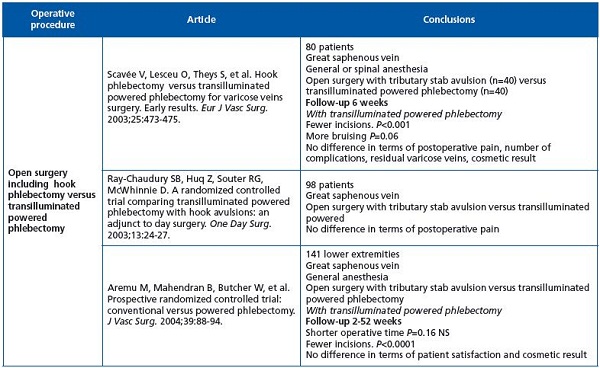

NB. Open surgery: high ligation + saphenous stripping +/- perforator ligation +/- tributary phlebectomy

Published data do not show any significant advantage of transilluminated powered phlebectomy (TIPP) over conventional phlebectomy, except for fewer incisions, but the reports refer to earlier generation systems and techniques. TIPP has become less traumatic with the newer systems, but there are no randomized clinical trials to show any benefits.

Abbreviations:

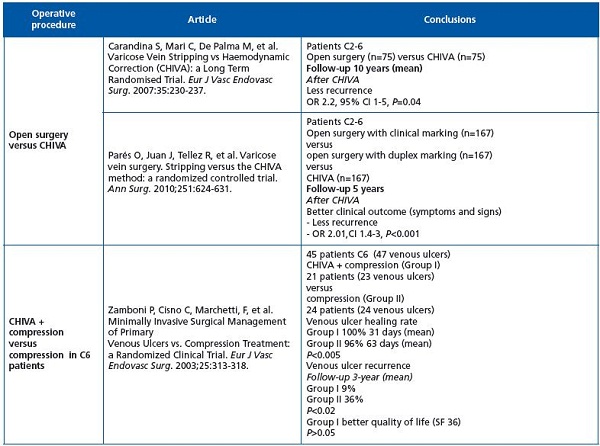

CHIVA = ambulatory conservative hemodynamic management of varicose veins

NB. Open surgery: high ligation + saphenous stripping +/- perforator ligation +/- tributary phlebectomy

When CHIVA1 was proposed in 1988, French phlebologists were divided in pro and con camps, as were the French people at the beginning of the previous century into dreyfusards and antidreyfusards.*

Many observational studies have been published on CHIVA techniques and outcome, but the first randomized clinical trial (RCT) appeared only 4 years ago.

As use of CHIVA has since moved mainly to Italy and Catalonia, it is not surprising that RCTs are performed in these parts of Europe. The Carandina RCT was limited to shunt I+II varicose veins according to the CHIVA nomenclature, while the article by Parés encompasses all kinds of primary varicose veins. Nevertheless, this large, well-documented randomized, open-label, controlled, single-center study raises some questions.

First, more than 90% of patients presented uncomplicated varicose veins (C2). Second, one outcome assessment is not considered in this article, the patient evaluation. This point is particularly important given that one of patients’ main complaints after CHIVA is a persistent cosmetic problem.

CHIVA + compression versus compression. The third RCT is limited to C6 patients, but also concludes that CHIVA is superior. Nevertheless one may be surprised by the healing rate, which is abnormally high in this series⎯100% in the CHIVA group and 96% in the compression group at 31 days, and 96% at 63 days, and also by the 9% recurrence rate at 3 years in the CHIVA group.

1. Franceschi C. Théorie et Pratique de la Cure Conservatrice et Hémodynamique de l’ Insuffisance Veineuse en Ambulatoire. Precy-sous- Thil, France: Editions de l’Armancon; 1988.

*Dreyfus affair (French: l’affaire Dreyfus) was a political event that divided France in the 1890s and early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent.

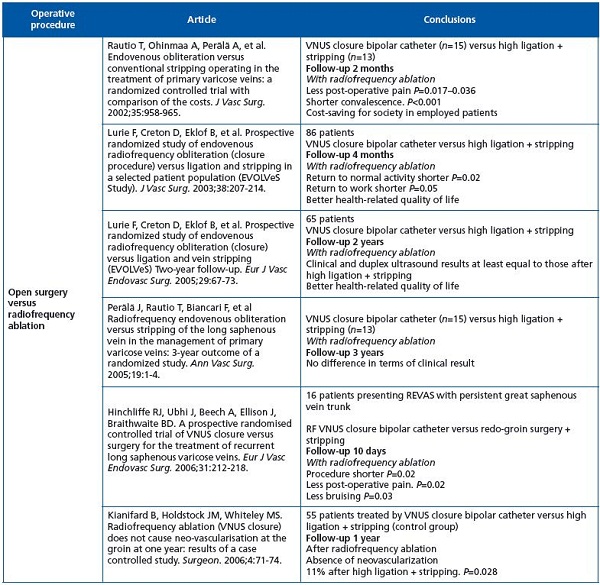

NB. Open surgery: high ligation + saphenous stripping +/- perforator ligation +/- tributary phlebectomy

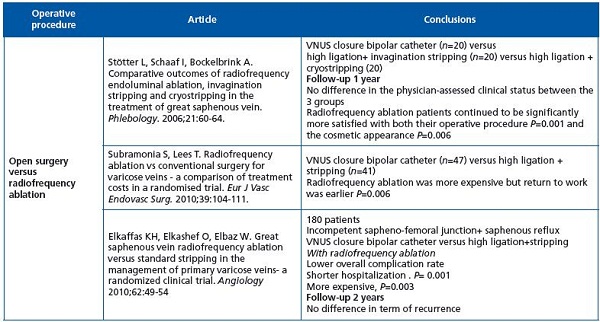

Seven randomized controlled trials (9 articles) have been identified and almost all of them conclude that after radiofrequency ablation there was less postoperative pain, faster recovery, and earlier return to work and normal activities, as well as greater patient satisfaction. The longest follow-up was 3 years and there was no difference in clinical results between classic surgery and radiofrequency ablation.

It should be noted that the bipolar catheter (Closure Plus) was used in all series, knowing that the new ClosureFast® catheter has given better results in published observations. It should, however, be pointed out that modern, less invasive open surgery under local anesthesia in the office setting is showing similar good outcomes.

NB. Open surgery: high ligation + saphenous stripping +/- perforator ligation +/- tributary phlebectomy

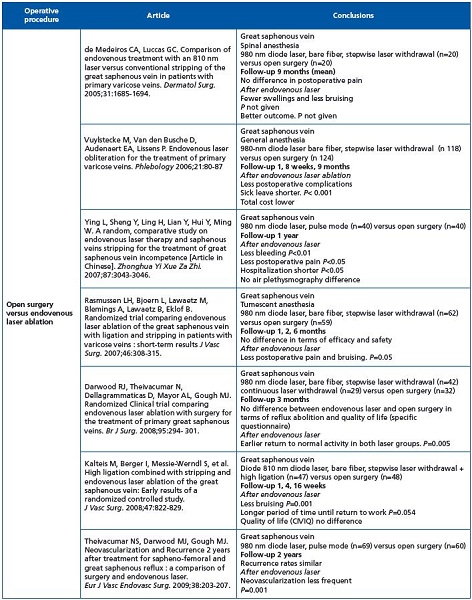

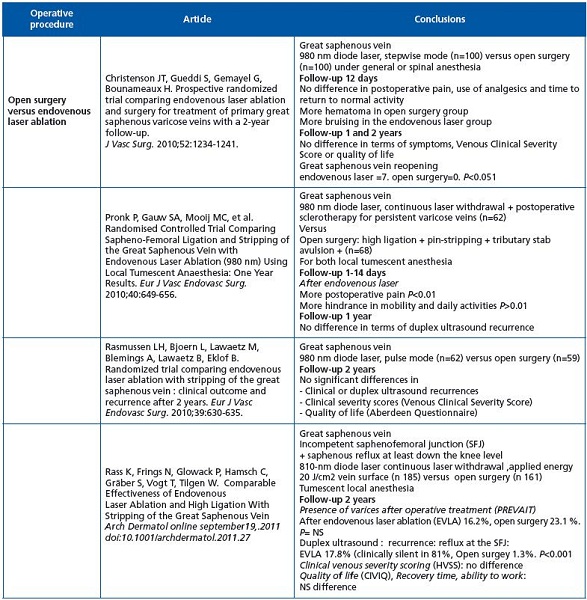

There are ten randomized controlled trials (11 articles) comparing classic open surgery with endovenous laser ablation. All except two used 980 nm bare-tipped fibers. Observation time was <2 years in 7 studies and >1 year in 3 studies. Quality of safety and early efficacy was high with no real difference between the groups. After two years no significant difference was found in clinical or duplex ultrasound recurrence, clinical severity, or quality of life. No randomized clinical trial has been reported with the new radial or jacket-tipped laser fibers.

REFERENCES

1. Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading Strength of Recommendations and Quality of Evidence in Clinical Guidelines. Report From an American College of Chest Physicians Task Force Chest. 2006;129:174-181.

2. Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Vist G E, et al. Grade: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924- 926.

3. Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Kunz R, et al. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995-998.

4. Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Kunz R, et al. Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:1049-1051.

5. Schünemann H J, Oxman A D, Brozek J, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008;336:1106-1110.

6. Guyatt G H, Oxman A D, Kunz R, et al. Incorporating considerations of resources use into grading recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:1170-1173.

7. Russell R. Surgical research. Lancet 1996;347:1480.

8. Black N. Evidence-based surgery: a passing fad? World J Surg 1999;23:789- 793.

9. Van der Linden W. Pitfalls in randomized surgical trials. Surgery 1980;87:258-262.

10. Devereaux PJ, Bhandari M, Clarke M, et al. Need for expertise based randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;330:88-91.