Management of venous ulceration (interventional treatments) with perspectives from a recent meta-analysis and recommendations

Clinique Pasteur, Toulouse, France

Abstract

Venous leg ulcers still affect about 1% of the adult population despite recent advances in chronic venous insufficiency treatment, and they represent a significant public health cost, estimated at between 1% and 2% of the annual health budget of Western European countries. Venous leg ulcers may be treated conservatively, with compression bandaging and wound care, medically, surgically, or with a combination of approaches, depending on the severity of the ulcer and available resources. The randomized trial of early endovenous ablation in venous ulceration demonstrated that early removal of a superficial venous reflux in patients with leg ulcer, combined with appropriate elastic compression, reduces healing time and increases time to recurrence without ulcer, assessed at 1-year follow-up. Thus, current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guidelines recommend early endovenous treatment in patients with venous ulcers. However, the relative benefit or indications for use of these interventional treatments (surgery, thermal ablation, nonthermal nontumescent techniques, subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery [SEPS], valvuloplasty, and stenting) remain to be definitively shown.

Introduction

Ulcers of the lower limbs are a major public health problem for which management requires further improvement, particularly in terms of healing time, prevalence, and recurrence rate. Ulcers of venous, or mixed arteriovenous and predominantly venous, origin represent the majority of leg ulcers with an estimated proportion of 70% to 80% of cases. They are painful, disabling conditions that are difficult to treat in a lasting way.

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) are common and affect up to 1% of the adult population; they represent a significant public health cost, estimated at between 1% and 2% of the annual health budget of Western European countries. Risk factors for venous ulcer correspond to those for chronic venous insufficiency: advanced age (peak between 60 and 80 years old), female sex, history of deep-vein thrombosis, family history of leg ulcer, personal history of obesity, trauma or leg surgery, number of pregnancies, and prolonged standing. The cost of in-home care for leg ulcers is about 235 million euros (nurses, dressings, antibiotics, and analgesics).

There are various guidelines around the world for the treatment of VLUs, which leads to a disparity in the treatment of patients worldwide. VLUs may be treated conservatively, with compression bandaging and wound care, medically, surgically, or with a combination of approaches, depending on the etiology, pathology, physiopathology, and the severity of the ulcer and available resources.

The current standard of care for chronic venous ulcers involves the use of compression bandages, and this is recommended as the initial standard treatment1,2; it exerts its effects in two ways: by reducing ambulatory venous pressure and raising interstitial tissue pressure by directly compressing at the ulcer and surrounding tissue, consequently reducing edema.3

In the prevention of recurrence of venous ulceration, a class 3 compression stocking should be used as it significantly reduces the recurrence rate over class 2.4

Dressings are applied beneath the compression and are used to control the exudate and to maintain the wound in a moist environment. In the case of a dry wound, a hydrogel and hydrocolloid dressing should be used, whereas highly absorbent dressings such as alginates, hydrofibers, or foam are more appropriate in the case of a highly exuding wound. Dressing changes should be as frequent as necessary.5,6

Other adjunct strategies include physical therapy; systemic drug treatments such as micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF), sulodexide, pentoxifylline, aspirin; split-thickness skin graft; and home- or community-based management.7-13

An international survey published in 2020 by Heatley et al shows that compression is used in 95% of cases if not contraindicated. Of the respondents (n=787), 78% believe that the treatment of superficial truncal venous reflux by endovenous intervention (radiofrequency or laser) or by surgery improves ulcer healing. Similarly, 80% of respondents believe that treatment of superficial truncal venous reflux by endovenous intervention or surgery reduces the recurrence rate in patients with chronic venous ulceration. Thermal ablation (laser or radiofrequency) alone was the most commonly used, followed by a combination of foam sclerosis and thermal ablation, followed by foam sclerosis alone and open surgery. Mechanochemical ablation (MOCA) and glue were the least used, probably for financial reasons. Finally, 59% of respondents perform endovenous intervention or surgery before the ulcer heals, 19% after healing, and 19% depending on circumstances.14

Interventional treatments

Apart from conservative methods, there are currently several techniques for correcting venous hypertension, which is at the origin of trophic disorders, including surgery but also sclerotherapy and endovenous thermal or nonthermal treatments.

The care strategy takes into account several criteria, specified in the Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, Physiological (CEAP) classification:

• anatomical distinction specifying whether they are superficial, deep, or perforating veins.

• aspects related to etiology, specifying whether it is a primary degenerative venous insufficiency or a secondary pathology, including post-thrombotic.

Treatment of superficial venous reflux

The EVRA study (Early Venous Reflux Ablation)15 provides the first level of evidence for the benefit of early endovenous treatment of superficial venous reflux in VLUs.

The complete healing time is significantly shorter in the “early removal” group (hazard ratio, 1.38; confidence interval, 1.13- 1.68; P=0.001) with a mean healing time in this group of 56 days, compared with 82 days in the delayed ablation group.

The mean healing rate at 1 year is 93.8% in the early ablation group versus 85.8% in the delayed ablation group. The average duration without ulcer is 306 days in the early ablation group and 278 days in the delayed ablation group with a recurrence rate at 1 year of 11% in the early ablation group and 16.5% in the delayed ablation group.

However, there was no significant difference on any of the quality-of-life measurement scales.

This study tends to demonstrate that early removal of a superficial venous reflux in patients with leg ulcer, combined with appropriate elastic compression, reduces the healing time and increases time to recurrence without ulcer as assessed at 1-year follow-up.

Surgery

The ESCHAR study (Effect of Surgery and Compression on Healing And Recurrence) has shown that surgical correction of superficial venous reflux in addition to compression bandaging does not improve ulcer healing but reduces the recurrence of ulcers at 4 years and results in a greater proportion of ulcer-free time.16 Ulcer healing rates at 3 years were 89% for the compression group and 93% for the compression plus surgery group (P=0.73, log rank test). Rates of ulcer recurrence at 4 years were 56% for the compression group and 31% for the compression plus surgery group (P<0.01).

In their study, Van Gent et al17 also report that the addition of surgical treatment in patients with venous ulceration leads to a significantly higher chance of being ulcer-free than ambulatory compression therapy alone. This effect persists after 10 years of follow-up, and the number of incompetent perforating veins has a significant effect on the ulcer state and recurrence.

Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy

Sclerosant is a chemical agent that damages the endothelium after injection. Foam can be obtained by mixing liquid sclerosant with air. The most frequently used method of producing foam is the Tessari technique, which consists of rapidly mixing 1 cc of liquid sclerosant with 4 cc of air. Sclerosing foam is more effective than liquid sclerosing agent and is injected by direct puncture or by catheter under ultrasound guidance.18

The technique of foam sclerotherapy has been described in a prospective study19 concerning C5/C6 diseases, with, for Pang et al, a healing rate comparable to that of surgery but a recurrence rate which appears to be lower.

O’Hare et al have published a randomized study comparing foam sclerotherapy associated with compression and compression alone in wound healing. The difference between the two groups is not significant, but recruitment is considered insufficient to conclude.20 Finally, a study published by Campos et al compares polidocanol foam sclerotherapy with surgery (n=56, C6, follow-up for 502±220 days): the ulcer healed in 100% and 91.3% of patients treated with surgery or foam sclerotherapy, respectively (P>0.05).21

Thermal treatments

Endovenous thermal ablation includes endovenous laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and steam ablation. Tumescent anesthesia is usually applied to prevent adjacent tissue injury from heat, compression, and of emptying the vein for proper contact of the catheter with the endothelium, and it pushes skin away from the catheter in case of shallow varicose veins (<1 cm from skin).

A randomized study evaluating the healing rate (n=52, C6) was carried out in two groups: endovenous laser plus compression or compression alone. After 12 months, Viarengo et al reported a healing rate of 81.5% in the group associated with compression and 24% in the group with compression alone. No recurrence was observed in patients treated with endovenous laser.22

In their randomized controlled trial (RCT) VUERT (Venous Ulcer: Endovenous Radiofrequency Treatment trial), Puggina et al compared radiofrequency plus compression (n=27) versus compression alone (n=29) and showed that RFA of insufficient saphenous and perforating veins plus multilayer compressive bandaging is an excellent treatment protocol for venous ulcer patients, because of its safety, effectiveness, and impact on ulcer recurrence reduction and clinical outcome (recurrence was lower in the radiofrequency group [P<0.001]).23

Nonthermal nontumescent treatments

Non-thermal techniques including MOCA and cyanoacrylate vein ablation have been developed with a view to removing thermal injury risk. The various techniques of nonthermal ablation that completely avoid the need for tumescent anesthesia reduces the time of the intervention, the per-intervention pain, the bruises, and the sensory nerve lesions.

O’Banion et al reported that a multi-institutional retrospective review of all CEAP 6 patients who underwent closure of their truncal veins from 2015-2020 was performed. A total of 119 patients were included with median follow-up of 105 days; 68 limbs were treated with RFA; and 51 limbs treated with VenaSeal. Median time to wound healing after procedure was significantly shorter for VenaSeal than RFA (43 vs 104 days, P=0.001). ClosureFast and VenaSeal are both safe and effective treatments to eliminate truncal venous insufficiency, and the ulcer recurrence rate was 19.3% (22.1% RFA vs 13.7%).24

In a retrospective review, Kim et al compared MOCA and thermal ablation (RFA and endovenous laser therapy) for venous ulcer healing in patients with clinical class 6 chronic venous insufficiency. They conclude that MOCA is safe and effective in treating VLU; younger age and use of MOCA favored wound healing, but randomized studies are necessary to further support their findings.25

Synthesis

In a Cochrane review aiming to look at potentially promising treatment with endovenous thermal ablation for healing venous ulcers and preventing recurrence as compared with compression therapy alone, Samuel et al found no RCTs that met inclusion criteria. They concluded that high-quality RCTs are urgently needed for implementation of this treatment in practice.”26

There is a meta-analysis of RCTs and observational comparative studies that we can refer to, which analyzes the effectiveness of all these surgical and intravenous methods in the context of ulcers. It concludes that such methods are not superior to compression alone on healing and rate of venous ulcer recurrence.27

There is a review showing the importance of the EVRA study,15 which tends to demonstrate that early removal of a superficial venous reflux in patients with leg ulcer, combined with appropriate elastic compression, reduces healing time and increase time to recurrence without ulcer, as seen at 1-year follow-up.

Treatment of perforating veins

The Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS)/American Venous Forum (AVF) Guideline Committee defines “pathologic” perforating veins as those with outward flow of 500 ms, a diameter of 3.5 mm, and location beneath a healed or open venous ulcer (CEAP class C5-C6).28

There is an RCT evaluation of the use of conventional surgery to eliminate the flow of perforating veins.29 The author notes a benefit of surgery in cases of recurrent or medial ulcers, where the time spent without ulcer is longer.

In their RCT, Nelzén et al report that adding subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery (SEPS) to superficial venous surgery is safe and effective for removing incompetent perforating veins in patients with a venous ulcer; however, they do not observe any detectable clinical benefit within 12 months of follow-up.30

In a Cochrane review of SEPS for treating VLUs, Lin et al report that the role of SEPS for the treatment of VLUs remains uncertain.31 However, percutaneous ablation either by ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy or endothermal ablation is recommended to avoid incision on the damaged skin in advanced chronic venous disease.32 The initial success rate after percutaneous ablation varies between 50% and 70%, and repeated procedure is common. Successful ablation is associated with ulcer healing in recalcitrant cases.33,34

Treatment of deep venous reflux

Venous reflux is a retrograde venous flow in an incompetent vein during ambulation in upright position. Treatment of reflux results in decreasing mean ambulatory venous hypertension, logically leading to ulcer healing and decreased recurrence.27

Surgery has a very specific place here: in the context of a primitive reflux, the most appropriate technique appears to be valvuloplasty, which has a 70% absence of recurrence of ulcers at 5 years. In the framework of a post-thrombotic syndrome, Maleti and Perrin report a 50% success rate at 5-year follow-up for clinical and hemodynamic results from transposition and transplantation. The clinical results for the new valves are encouraging.35

Treatment of deep venous obstruction

Iliocaval vein obstruction can occur after deep-vein thrombosis or can be related to external compression. Iliac vein lesion has been shown to be the significant cause of chronic venous disease, with a 20% prevalence in two studies.36,37

The standard treatment in iliocaval vein obliteration is endovascular angioplasty with mandatory stenting.

Treatment of chronic venous ulcer

We include in this overview from “ESCHAR to EVRA” a multicenter retrospective cohort study that used a standardized database to evaluate patients with chronic venous ulcers treated between January 2013 and December 2017 (n=832).38

At 36 months of follow-up, the ulcer healing rates according to treatment were: 75% of the 187 patients treated by compression and wound care management alone, 51% of patients who underwent truncal vein ablation alone, 68% of patients who received both superficial and perforator ablation, 77% of those who underwent stent placement alone, and 87% of those who underwent deep-venous stenting and ablation of both incompetent truncal and perforator veins.

Interventional treatment when deep anomalies (combination of obstruction and reflux) are associated with superficial venous reflux

Currently, the literature does not define precisely whether deep or superficial treatment should be performed first. However, 3 articles give us some interesting insights, discussed here.

The May-Thurner syndrome (also known as Cockett’s syndrome) is thought to be a relatively rare contributor to chronic venous disease, predominantly affecting the left lower extremity of young women. In his study, Raju36 shows that stenting alone (nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions), without correction of associated reflux, often brings relief. The cumulative results observed 2.5 years after stent placement in the nonthrombotic-iliac-vein-lesion subsets with reflux and without reflux indicated complete stasis ulcer healing in 67% and 76%, respectively. The relationship between superficial and deep venous reflux and why deep venous reflux is sometimes resolved after greater saphenous treatment needs further investigation.

In Puggioni’s series,39 after greater saphenous vein ablation, deep reflux disappeared in only 24% of limbs, and reflux time and velocity did not significantly improve.

Maleti et al40 show in their study that the failure to correct deep axial reflux by superficial ablation in patients with superficial and associated primary deep axial reflux may be related to asymmetry in the leaflets of the incompetent deep venous valve. If the valves are symmetrical, it is advisable to first treat the superficial system alone. Conversely, if they are asymmetrical, valvuloplasty associated with varicose vein ablation might be indicated.

Recommendations

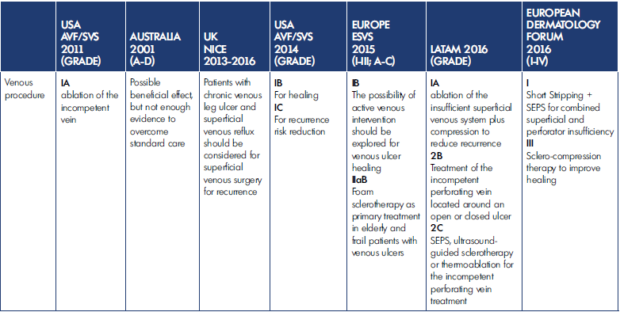

Gianesi et al published “Global guidelines trends and controversies in lower limb venous and lymphatic disease: Narrative literature revision and experts’ opinions following the vWINter international meeting in Phlebology, Lymphology & Aesthetics, 23–25 January 2019”41 and summarize the indications to interventional procedures for venous ulcer management in Table I below.

Although a general agreement toward the application of procedures in venous ulcer management exists in all the guidelines evaluated, there is significant heterogeneity in the reported grade of evidence.

The EVRA trial demonstrated that early removal of a superficial venous reflux in patients with leg ulcer, combined with appropriate elastic compression, reduces healing time and increases time to recurrence without ulcer as assessed at 1-year follow-up. Thus, NICE currently recommends early endovenous treatment in patients with venous ulcers.

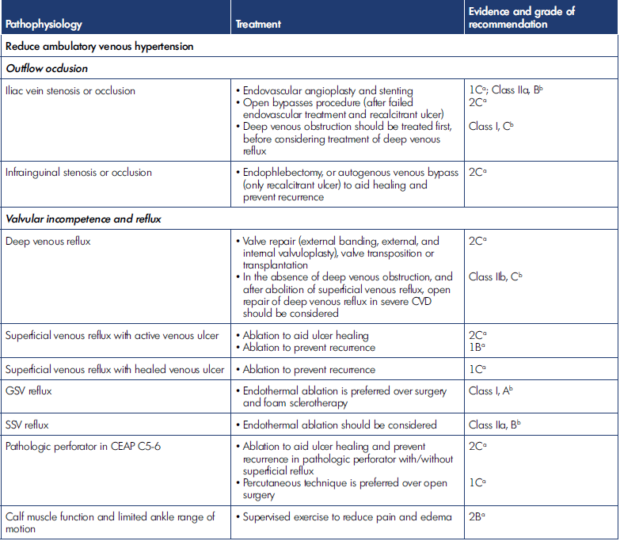

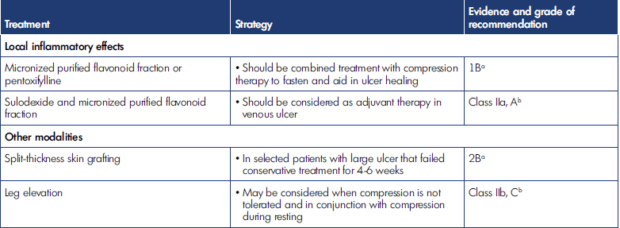

Siribumrungwong et al summarized treatment modalities other than compression therapy to manage VLU according to pathophysiology and includes guideline evidence in Table II below.42 Table III indicates adjunct treatment strategies to compression therapy alone.42

Table I. Indications for interventional procedures for venous ulcer management. After reference 41: Gianesini et al. Phlebol J Venous Dis. 2019;34(1 suppl):4‑66. © 2019, SAGE Publications. AVF, American Venous Forum; ESVS, European Society for Vascular Surgery; LATAM, Latin American Working Group; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SEPS, subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery; SVS, Society for Vascular Surgery.

Table II. Non–compression therapy treatment modalities for venous leg ulcer management, according to pathophysiology. After reference 42: Siribumrungwong et al. Compression and Chronic Wound Management [Internet]. 2019:81-103. Cham: Springer International Publishing. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-01195-6_5. © 2019, Springer Nature Switzerland. CEAP, Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, Pathophysiological classification; CVD, chronic venous disease; GSV, great saphenous vein; SSV, small saphenous vein. Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum 2014.2 Grade of recommendation: 1, strong; 2, weak recommendation. Level of evidence: A, high; B, moderate; C, low quality. Clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 2015.1 Class of recommendation: I, treatment beneficial, recommended; II, conflicting evidence and/or divergence, opinion; IIa, favor of usefulness and efficacy; IIb, usefulness/efficacy is less well established; III, treatment not useful, not recommended. Level of evidence: A, from meta-analysis or multiple randomized controlled trials; B, single randomized controlled trial, or large nonrandomized studies; C, consensus, retrospective studies, or registries.

Table III. Adjunct treatment strategies for venous leg ulcer management (in combination with compression therapy). After reference 42: Siribumrungwong et al. Compression and Chronic Wound Management [Internet]. 2019:81-103. Cham: Springer International Publishing. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-01195-6_5. © 2019, Springer Nature Switzerland. Clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum 2014.2 Grade of recommendation: 1, strong; 2, weak recommendation. Level of evidence: A, high; B, moderate; C, low quality. Clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery 2015.1 Class of recommendation: I, treatment beneficial, recommended; II, conflicting evidence and/or divergence, opinion; IIa, favor of usefulness and efficacy; IIb, usefulness/efficacy is less well established; III, treatment not useful, not recommended. Level of evidence: A, from meta-analysis or multiple randomized controlled trials; B, single randomized controlled trial, or large nonrandomized studies. C; consensus, retrospective studies, or registries.

Conclusion

VLUs still affect about 1% of the adult population despite recent advances in chronic venous insufficiency treatment. After confirming the diagnosis of venous ulcer, 3 main lines of treatment are considered: adjunctive treatment, concomitant treatment of the cause of venous hypertension, and compression therapy.

A recently published RCT (EVRA) suggests benefit of early, as compared with deferred, endovascular ablation for those with VLUs in terms of reduced healing time and extended ulcer free recurrence time.

However, the relative benefit or indications for use of these interventional treatments (surgery, sclerotherapy, thermal ablation, nonthermal nontumescent techniques, SEPS, valvuloplasty, and stenting) remain to be definitively shown.

Percutaneous ablation either by ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy or endothermal ablation is recommended to avoid incision on the damaged skin in advanced chronic venous disease; the potential benefits, in particular a reduced risk of nerve damage associated with nonthermal techniques, might be of considerable clinical importance and may lead to a preference for such techniques in the future.

REFERENCES

1. Wittens C, Davies AH, Bækgaard N, et al. Editor’s choice – Management of chronic venous disease: clinical practice guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;49(6):678‑737.

2. O’Donnell TF, Passman MA, Marston WA, et al. Management of venous leg ulcers: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery_ and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(2):3S-59S.

3. Nehler MR, Moneta GL, Woodard DM, et al. Perimalleolar subcutaneous tissue pressure effects of elastic compression stockings. J Vasc Surg. 1993;18(5):783‑788.

4. Milic DJ, Zivic SS, Bogdanovic DC, Golubovic MD, Lazarevic MV, Lazarevic KK. A randomized trial of class 2 and class 3 elastic compression in the prevention of recurrence of venous ulceration. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6(6):717‑723.

5. Alavi A, Sibbald RG, Phillips TJ, et al. What’s new: management of venous leg ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(4):643‑664.

6. Mosti G. Wound care in venous ulcers. Phlebology. 2013;28(1 suppl):79‑85.

7. Brown A. Life-style advice and self-care strategies for venous leg ulcer patients: what is the evidence? J Wound Care. 2012;21:342‑344, 346, 348.

8. Smith PC. MPFF at a dose of 500 mg and venous leg ulcer: new results from a meta-analysis. Angiology. 2005;56(6 suppl):S33‑S39.

9. Wu B, Lu J, Yang M, Xu T. Sulodexide for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. Accessed February 6, 2021. https:// www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/ doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010694. pub2/full

10. Jull AB, Arroll B, Parag V, Waters J. Pentoxifylline for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2012. Accessed February 6, 2021. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/ cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001733. pub3/full

11. de Oliveira Carvalho PE, Magolbo NG, De Aquino RF, Weller CD. Oral aspirin for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Wounds Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. Published February 18, 2016. Accessed February 6, 2021. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858. CD009432.pub2

12. Jull A, Wadham A, Bullen C, Parag V, Kerse N, Waters J. Low dose aspirin as adjuvant treatment for venous leg ulceration: pragmatic, randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial (Aspirin4VLU). BMJ. 2017;359:j5157.

13. Serra R, Rizzuto A, Rossi A, et al. Skin grafting for the treatment of chronic leg ulcers – a systematic review in evidence-based medicine. Int Wound J. 2017;14(1):149‑157.

14. Heatley F, Onida S, Davies AH. The global management of leg ulceration: pre early venous reflux ablation trial. Phlebol J Venous Dis. 2020;35(8):576‑582.

15. Gohel MS, Heatley F, Liu X, et al. Early versus deferred endovenous ablation of superficial venous reflux in patients with venous ulceration: the EVRA RCT. Health Technol Assess Winch Engl. 2019;23(24):1‑96.

16. Gohel MS, Barwell JR, Taylor M, et al. Long term results of compression therapy alone versus compression plus surgery in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR): randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335(7610):83.

17. van Gent WB, Catarinella FS, Lam YL, et al. Conservative versus surgical treatment of venous leg ulcers: 10-year follow up of a randomized, multicenter trial. Phlebology. 2015;30(1 suppl):35‑41.

18. van Eekeren RRJP, Boersma D, de Vries J-PPM, Zeebregts CJ, Reijnen MMPJ. Update of endovenous treatment modalities for insufficient saphenous veins—a review of literature. Semin Vasc Surg. 2014;27(2):118‑136.

19. Pang KH, Bate GR, Darvall K AL, Adam DJ, Bradbury AW. Healing and recurrence rates following ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy of superficial venous reflux in patients with chronic venous ulceration. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40(6):790‑795.

20. O’Hare JL, Earnshaw JJ. Randomised clinical trial of foam sclerotherapy for patients with a venous leg ulcer. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39(4):495‑499.

21. Campos W, Torres IO, Silva ES da, Casella IB, Puech-Leão P. A Prospective randomized study comparing polidocanol foam sclerotherapy with surgical treatment of patients with primary chronic venous insufficiency and ulcer. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29(6):1128‑1135.

22. Viarengo LMA, Potério-Filho J, Potério GMB, Menezes FH, Meirelles GV. Endovenous laser treatment for varicose veins in patients with active ulcers: measurement of intravenous and perivenous temperatures during the procedure. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33(10):1234‑1242.

23. Puggina J, Sincos IR, Campos W, et al. A randomized clinical trial of the effects of saphenous and perforating veins radiofrequency ablation on venous ulcer healing (VUERT trial). Phlebology. 2020;0268355520951697.

24. O’Banion LAA, Reynolds KB, Kochubey M, et al. Treatment of superficial venous reflux in CEAP 6 patients: a comparison of cyanoacrylate glue and radiofrequency ablation techniques. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(3):e336‑e337.

25. Kim SY, Safir SR, Png CYM, et al. Mechanochemical ablation as an alternative to venous ulcer healing compared with thermal ablation. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2019;7(5):699‑705.

26. Samuel N, Carradice D, Wallace T, Smith GE, Chetter IC. Endovenous thermal ablation for healing venous ulcers and preventing recurrence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(10):CD009494.

27. Mauck KF, Asi N, Undavalli C, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical interventions versus conservative therapy for venous ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(2):60S-70S.e2.

28. Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, Dalsing MC, et al. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(5):2S-48S.

29. van Gent WB, Hop WC, van Praag MC, Mackaay AJ, de Boer EM, Wittens CH. Conservative versus surgical treatment of venous leg ulcers: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(3):563‑571.

30. Nelzén O, Fransson I, Swedish SEPS Study Group. Early results from a randomized trial of saphenous surgery with or without subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery in patients with a venous ulcer. Br J Surg. 2011;98(4):495‑500.

31. Lin ZC, Loveland PM, Johnston RV, Bruce M, Weller CD. Subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery (SEPS) for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD012164.

32. Mosti G, De Maeseneer M, Cavezzi A, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery and American Venous Forum Guidelines on the management of venous leg ulcers: the point of view of the International Union of Phlebology. Int Angiol J Int Union Angiol. 2015;34(3):202‑218.

33. Lawrence PF, Alktaifi A, Rigberg D, DeRubertis B, Gelabert H, Jimenez JC. Endovenous ablation of incompetent perforating veins is effective treatment for recalcitrant venous ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(3):737‑742.

34. Masuda EM, Kessler DM, Lurie F, Puggioni A, Kistner RL, Eklof B. The effect of ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy of incompetent perforator veins on venous clinical severity and disability scores. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43(3):551‑557.

35. Maleti O, Perrin M. Reconstructive surgery for deep vein reflux in the lower limbs: techniques, results and indications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41(6):837‑848.

36. Raju S, Neglen P. High prevalence of nonthrombotic iliac vein lesions in chronic venous disease: a permissive role in pathogenicity. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(1):136‑144.

37. Neglén P, Thrasher TL, Raju S. Venous outflow obstruction: an underestimated contributor to chronic venous disease. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(5):879‑885.

38. Lawrence PF, Hager ES, Harlander-Locke MP, et al. Treatment of superficial and perforator reflux and deep venous stenosis improves healing of chronic venous leg ulcers. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(4):601‑609.

39. Puggioni A, Lurie F, Kistner RL, Eklof B. How often is deep venous reflux eliminated after saphenous vein ablation? J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(3):517‑521.

40. Maleti O, Lugli M, Perrin M. After superficial ablation for superficial reflux associated with primary deep axial reflux, can variable outcomes be caused by deep venous valve anomalies? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53(2):229‑236.

41. Gianesini S, Obi A, Onida S, et al. Global guidelines trends and controversies in lower limb venous and lymphatic disease: narrative literature revision and experts’ opinions following the vWINter international meeting in Phlebology, Lymphology & Aesthetics, 23–25 January 2019. Phlebol J Venous Dis. 2019;34(1 suppl):4‑66.

42. Siribumrungwong B, Orrapin S, Mani R, Rerkasem K. Surgical solutions are an alternative to compression bandaging in venous leg ulcer. In: Mani R, Rerkasem K, Nair HKR, Shukla V, eds. Compression and Chronic Wound Management [Internet]. 2019:81-103. Cham: Springer International Publishing. Accessed February 7, 2021. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3- 030-01195-6_5