Extended treatment of venous thromboembolism

Paolo Prandoni, MD, PhD

Arianna Foundation on

Anticoagulation, Bologna, Italy

ABSTRACT

After discontinuing anticoagulation, the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients suffering an episode of unprovoked or weakly provoked VTE ranges between 30% and 50%, the rate being higher in patients with primary deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Baseline parameters that increase this risk are male sex, obesity, carriership of thrombophilia, proximal location of DVT, and renal failure. While the latest international guidelines suggest indefinite anticoagulation for most such patients, new scenarios are being offered through the availability of risk stratification models that have the potential to identify patients in whom anticoagulation can be safely discontinued because of a low risk of recurrence, and those in whom extending anticoagulation is undesirable because of a high risk of bleeding. Low-dose apixaban and rivaroxaban are the mainstay of extended treatment of VTE in all patients, except those who are carriers of the antiphospholipid syndrome. As an alternative, low-dose aspirin and sulodexide have been reported to decrease the risk of recurrent events by 30% to 50% without increasing the bleeding risk.

Clinical case

A 76-year-old male presented with unprovoked deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in his left leg, without symptoms of pulmonary embolism (PE). Compression ultrasonography confirmed DVT, showing incompressibility of the popliteal vein and of the distal segment of the superficial femoral vein. He had no personal or family history of venous thromboembolism (VTE), and tests for thrombophilia and occult malignancy were negative. He was treated with apixaban, starting with a loading dose of 10 mg twice daily for 1 week, followed by 5 mg twice daily for 6 months. Repeat ultrasonography showed recanalization of the previously affected veins. The question now is whether to discontinue anticoagulation, continue with the same dose, or switch to a low-dose regimen (2.5 mg twice daily) of apixaban.

Rationale for extending anticoagulation in patients

with unprovoked or weakly provoked venous

thromboembolism

with unprovoked or weakly provoked venous

thromboembolism

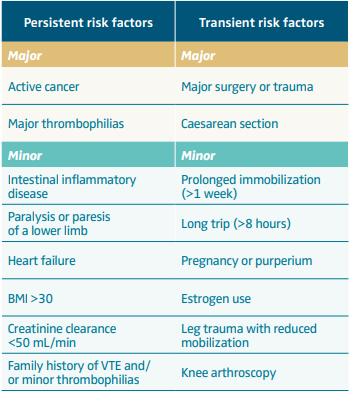

The optimal duration of anticoagulation in patients presenting with a first episode of proximal DVT and/or PE remains controversial. Historically, most patients with VTE (ie, all except those with major persistent risk factors, such as cancer) had their treatment discontinued after 3 months.1 Recent evidence and new guidance suggest that this approach is overly simplistic, as it fails to consider patients with VTE that is either unprovoked or associated with minor (transient or persistent) risk factors, which are summarized in Table I.

Table I. Risk factors of venous thromboembolism.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kg/height in m2); VTE, venous thromboembolism.

The risk of recurrent VTE after discontinuing anticoagulation in patients with a first episode of unprovoked or weakly provoked VTE was assessed in a recent comprehensive meta-analysis of 18 studies.2 Overall, the risk of recurrent VTE was found to be high, approaching 30% and 40% after 5 and 10 years, respectively, in men; 20% and 30%, respectively, in women. Besides male sex, factors that were found to be consistently associated with an increased risk of recurrent VTE were the proximal location of DVT, obesity, thrombophilia, and renal failure.2 This risk is not impacted by the duration of anticoagulation prior to its discontinuation. Indeed, based on the analysis of individual participant data from 7 randomized clinical studies addressing different durations of anticoagulation, prolonging anticoagulation beyond the first 3 months up to 6, 12, or even 27 months was associated with a similarly high risk of recurrent VTE once anticoagulation was discontinued.3 These findings have recently been confirmed by those of PADIS PE (Prolonged Anticoagulation During Eighteen Months vs Placebo After Initial Six-month Treatment for a First Episode of Idiopathic Pulmonary Embolism), a multicenter randomized clinical trial performed in France, where approximately 400 patients with unprovoked PE were randomized to receive either 6 or 18 months of anticoagulation.4

Patients with a first symptomatic DVT are at higher risk of recurrent VTE than those with a first unprovoked PE.5 In addition, patients with clinically symptomatic PE have consistently been found to be at a higher risk of recurrent PE than those with DVT alone. These findings have recently been confirmed by a patient-level meta-analysis.6 According to the same meta-analysis, the clinical presentation with PE (alone or associated with DVT) increases by more than 3 times the risk of a new PE episode over the clinical presentation with isolated DVT.6

Unfortunately, prolonging anticoagulation beyond the first 3 to 6 months with the use of vitamin K antagonists (VKA) exposes to a high risk of unpredictable major bleeding complications.7 In addition, whereas the expected rate of fatal bleeding during anticoagulation for 1000 patient-years is comparable to that of fatal (recurrent) PE, the case-fatality rate of major bleeding complications (consistently around 10% to 12%) is considerably higher than that (3%-4%) for recurrent VTE events.8

Accordingly, administering for a fixed duration an anticoagulation therapy—except for patients at high risk of bleeding complications—and administering on a routine basis an indefinite treatment with VKA after a first episode of VTE that is either unprovoked or associated with weak risk factors of thrombosis should both be abandoned. An exception should be made for carriers of the antiphospholipid syndrome, as extended treatment with VKA has consistently been shown to be associated with the best benefit/risk profile.9

Alternative scenarios

In a clinical trial that was published 20 years ago, administering after the first months of conventional treatment a low intensity warfarin therapy (that is, a dose that produces an international normalized ratio ranging between 1.5 and 2.0) was found to be more effective than placebo, even when major bleeding complications occurring during warfarin anticoagulation were taken into account.10 However, in a simultaneous head-to-head comparison, low-dose warfarin therapy was found to be significantly less effective than the conventional approach.11 Accordingly, this strategy has virtually been abandoned.

Two studies addressed the efficacy of low-dose aspirin for prevention of recurrent VTE.12,13 When data from these 2 trials are pooled, there is a 30% to 35% reduction in the rate of both recurrent VTE and major vascular events. Moreover, these benefits are achieved with a negligible risk of bleeding.14 In addition, favorable results have been observed with the use of sulodexide in the SURVET study (Multicentre, Randomised, Double Blind, Placebo Controlled Study on Long Term Treatment with Sulodexide for Prevention of Recurrent DVT in Patients with Venous Thromboembolism). In this double-blind study, approximately 600 patients with a first unprovoked VTE who had completed 3 to 12 months of oral anticoagulant treatment were randomly assigned to sulodexide (500 U twice daily) or placebo for 2 years. The rate of recurrent events was found to be twice lower in patients randomized to sulodexide than in those allocated to placebo. No major bleeding episodes occurred in either group.15

Hence, based on available evidence, aspirin in low doses and sulodexide may offer a safe and cost-effective option for the long-term prevention of recurrent VTE. However, the extent by which they reduce the rate of recurrent VTE (30%-50%) is remarkably lower than that achievable with the current anticoagulant drugs. Thus, they can only be considered in selected patients in whom old and novel anticoagulants are not accepted by patients or are contraindicated.

Direct oral anticoagulants

In the AMPLIFY-EXT study (Efficacy and Safety Study of Apixaban for Extended Treatment of Deep Vein Thrombosis or Pulmonary Embolism), apixaban in low preventive doses (2.5 mg twice daily), administered for 1 year after the first 6 months of conventional anticoagulation in more than 2500 patients with unprovoked VTE, was found to be as effective as conventional doses (5 mg twice daily).16 Each of the 2 apixaban doses reduced by almost 90% the risk of recurrent VTE over placebo. The bleeding risk was similarly low in all 3 study arms. Of interest, the rate of combined major and clinically relevant non-major bleeding did not differ between low-dose apixaban and placebo.16

In the EINSTEIN CHOICE study (Reduced-dose Rivaroxaban in the Long-term Prevention of Recurrent Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism), published a few years later, almost 3500 patients in whom there was uncertainty about the optimal long-term treatment (thus including a substantial proportion of patients with provoked VTE) were randomized to receive— after the first 6 months of conventional anticoagulation—20 mg of rivaroxaban, 10 mg of rivaroxaban, or low-dose aspirin for 1 year.17 Each of the 2 rivaroxaban doses reduced by 70% the rate of recurrent VTE over aspirin, and the bleeding risk was similarly low in all 3 study groups. The results were, therefore, fully consistent with those shown for apixaban in the AMPLIFY-EXT study. Whereas no patients with VTE associated with major surgery or trauma developed recurrent events, in all other patient categories, the risk of VTE while on low-dose aspirin was substantial and was reduced by each of the 2 rivaroxaban doses.

These findings are consistent with those achieved in an analysis where the results of the EINSTEIN CHOICE study were combined with those of the EINSTEIN EXTENSION study (Once-daily Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor Rivaroxaban in the Long-term Prevention of Recurrent Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism in Patients With Symptomatic Deep-vein Thrombosis or Pulmonary Embolism).18 To this purpose, identifiable risk factors were stratified according to the classification indicated in Table I. In this combined analysis, once again, whereas in the patient category for VTE associated with major surgery or trauma no patients developed recurrent events, in all other patient categories (including unprovoked VTE and VTE associated with minor risk factors) the risk of VTE while on low-dose aspirin and even more so on placebo was substantial and was reduced by each of the 2 rivaroxaban doses. However, whether administering low-dose direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in all patients with unprovoked or weakly provoked VTE is the most proper strategy is still a matter of debate.

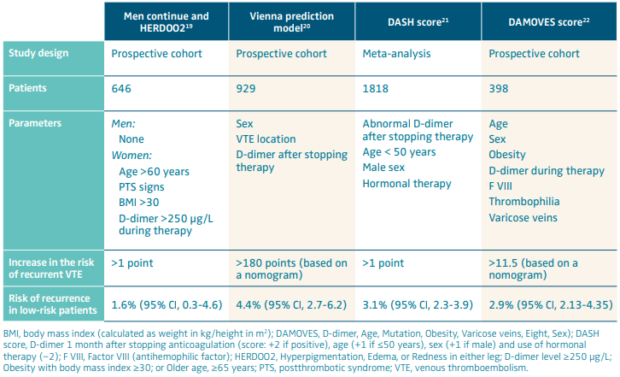

Risk stratification models

Several stratification models have been derived and validated, which have the potential to identify those patients in whom anticoagulation can be safely discontinued (Table II).19-22 The most suitable is the Canadian model HERD002 (hyperpigmentation, edema, or redness in either leg; D-dimer level ≥250 μg/L; obesity with body mass index ≥30; or older age, ≥65 years). In the derivation study, women with idiopathic VTE and none or 1 of several parameters (including age older than 60, obesity, D-dimer >250 μg/L at time of discontinuing anticoagulation, and postthrombotic manifestations) exhibited a considerably low risk of recurrent VTE.19 These findings have subsequently been confirmed by those of a validation study23 and have found strong support in a recent subanalysis of the Canadian REVERSE study (REcurrent VEnous Thromboembolism Risk Stratification Evaluation) dealing with women with VTE associated with the use of contraceptive pills.24

The serial D-dimer approach, which had been shown in the DULCIS (D-dimer and ULtrasonography in Combination Italian Study) and MORGAGNI (Optimal Duration of Anticoagulation in Deep Venous Thrombosis) studies to identify patients in whom anticoagulation can be safely discontinued,25,26 has surprisingly failed to confirm its value in the recently published APIDULCIS study (Apixaban for Extended Anticoagulation), a prospective cohort multicenter Italian study.27 More than 800 patients with a first episode of unprovoked or weakly provoked VTE who had completed at least 12 months of anticoagulation had D-dimer measured at baseline and, if negative, 3 more times in the following 2 months. In patients with serially negative D-dimer, anticoagulation was permanently interrupted. All other patients were given low-dose apixaban (2.5 mg twice daily). All patients were followed-up for up to 18 months. Disappointingly, patients managed with the serial assessment of D-dimer experienced an unacceptably high rate of recurrent symptomatic VTE over the prespecified follow-up, whereas the rate of events in the group of patients (approximately 50% of all recruited patients) who had been administered low-dose apixaban was low. However, the results of the APIDULCIS study may have been impacted by the pandemic.28 In addition, a successful management with the serial D-dimer approach could not be excluded in females.27,28 These findings are consistent with those coming from a recent subanalysis of the Canadian REVERSE study29 and suggest that, at least in males, the serial D-dimer approach should be abandoned and replaced by extended treatment with low-dose apixaban or rivaroxaban for the long-term management of patients with unprovoked or weakly provoked VTE.

Table II. Risk stratification models for the assessment of the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with unprovoked or weakly provoked venous thromboembolism.

Assessing the bleeding risk

Before embarking on an indefinite treatment regime with low dose DOACs, the bleeding risk should be carefully evaluated. Recently, results were published for a meta-analysis of 27 prospective cohort or randomized clinical trials that had addressed the long-term follow-up of patients with unprovoked VTE in the last 30 years.30 According to the findings of this meta-analysis, the rate of major bleeding complications while on DOAC treatment (annual rate, 1.2%), although lower than that (2.0%) reported in patients managed with VKAs, was not negligible. In addition, the case-fatality rate of major bleeding complications did not differ between patients managed with VKA and DOAC. Factors that were found to be independently associated with the risk of major bleeding were elderly age, renal failure, history of bleeding, simultaneous antiplatelet therapy, and severe anemia.

Although accurate estimation of major bleeding risk is essential to help optimize the long-term management of patients with unprovoked VTE, the scientific community has remained without a valid tool until recently. As a result of a multicenter, international collaboration, a model has been developed and externally validated (the VTE-PREDICT risk score), which has the potential to help physicians establish both the risk of recurrent VTE (after discontinuing anticoagulation) and that of major bleeding (while on anticoagulation) following the initial treatment in all VTE patients free of cancer based on a few readily available patient characteristics, including several demographics and clinical parameters (age, sex, body mass index, blood pressure), nature of the thrombotic episode (primary DVT or PE), risk factors of thrombosis (surgery, trauma, immobilization, estrogen therapy), medical history (cancer, VTE, bleeding, stroke), laboratory values (hemoglobin) and comedications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs).31 The model can be freely retrieved (vtepredict.com). After including step-by-step requested information, physicians and patients are given the predicted risk of recurrent VTE (after discontinuing anticoagulation) and that of major bleeding (while on anticoagulation) over the following 5 years.

Finally, in a prospective multinational cohort study of patients with unprovoked (or weakly provoked) VTE receiving extended anticoagulation after completing at least 3 months of initial treatment, Wells and coworkers were able to identify and internally validate a novel model (the CHAP [creatinine, hemoglobin, age, and use of antiplatelet agent] model), which has the potential to accurately discriminate between patients at high and low risk of major bleeding, defined as higher and lower than 2.5 events per 100 patient-years, respectively.32 This model includes only four easily retrievable parameters (creatinine, hemoglobin, age, and the concomitant use of an antiplatelet agent). The annual rate of major bleeding can be easily calculated on individual basis with the use of the following formula: 0.02 x [(creatinine in µmol/L x 0.0017) + (hemoglobin in g/L x -0.0127) + (age x 0.0251) + (1 x 0.8995 in case of antiplatelet use)]. The CHAP model was found to accurately discriminate between patients with unprovoked or weakly provoked VTE at high and low risk of major bleedings while on extended anticoagulation. Its value has recently been supported by a retrospective analysis of findings from the international RIETE registry (Registro Informatizado de Enfermedad TromboEmbólica).33

In a context dominated by uncertainty about the optimal management of patients with unprovoked VTE, pending the scarce reliability of available bleeding prediction models, the VTE-PREDICT and the CHAP models have the potential to provide clinicians with a useful tool to balance the thrombotic risk with the hemorrhagic risk when deciding the intensity and duration of anticoagulation, and they qualify as pivotal steps in the prognostic assessment of patients with unprovoked VTE.

The role of age

Among factors that are expected to increase the risk of (major) bleeding complications is elderly age.30 Not surprisingly, therefore, the prolongation of anticoagulation beyond the initial 3 to 6 months in patients over 75 years of age is generally discouraged.34 However, this recommendation can only be justified if the risk of recurrent VTE in patients in whom anticoagulation is discontinued does not exceed that expected in younger individuals. The risk of recurrent VTE beyond the age of 75 has recently been assessed in the framework of the RIETE registry.35 Almost 25 000 patients at their first episode of VTE, of whom approximately one-third were aged over 75, were followed-up for up to 3 years after discontinuing anticoagulation. After adjusting for the baseline characteristics, the hazard ratio of recurrent VTE showed no difference between subjects older and younger than 75 (1.03; 95% CI, 0.92–1.17). These findings are consistent with those coming from the Asiatic COMMAND-VTE registry (multicenter registry enrolling 3027 consecutive patients with acute symptomatic VTE in Japan between January 2010 and August 2014).36 Accordingly, elderly age, which is a well-known risk factor for venous thrombosis, does not seem to increase the risk of recurrent VTE in patients older than 75 who develop a first thromboembolic episode. As in these individuals the risk of bleeding complications while on anticoagulation exceeds that reported in younger people,30 the decision about extending anticoagulant drugs after the first 3 to 6 months should be carefully balanced against the hemorrhagic risk with the help of the aforementioned risk assessment models.31,32

Discussion of the clinical case

The development of an unprovoked episode of proximal DVT in a male individual is a strong indication for prolonging, indefinitely, anticoagulation with low-dose DOACs, provided there are no contraindications and risk assessment models indicate a favorable benefit/risk profile. Despite the patient’s age, the risk models (VTE-PREDICT, CHAP) suggest continuing anticoagulation is appropriate. The patient agreed to prolong anticoagulation and to refer to the thrombosis center on an annual basis for periodic reassessments.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in addition to carriers of cancer and those with major thrombophilias and other conditions requiring an indefinite anticoagulation therapy, extended treatment of VTE should be considered in males with a first episode of unprovoked or weakly provoked VTE, provided the hemorrhagic risk (as assessed with the CHAP or VTE-PREDICT model) is low. In women, the decision may be guided by a stratification model (HERD002 or serial D-dimer). This is especially valid for sex-related VTE (ie, VTE related to hormonal therapy, pregnancy, or delivery). The drugs to be favored are apixaban or rivaroxaban in preventive doses.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Dr Paolo Prandoni

Arianna Foundation on Anticoagulation,

Via P. Fabbri 1/3 –

40138, Bologna, Italy

EMAIL: prandonip@gmail.com

References

1. Weitz JI, Prandoni P, Verhamme P. Anticoagulation for patients with venous thromboembolism: when is extended treatment required? TH Open. 2020;4(4):e446-e456.

2. Khan F, Rahman A, Carrier M, et al. Long term risk of symptomatic recurrent venous thromboembolism after discontinuation of anticoagulant treatment for first unprovoked venous thromboembolism event: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;366:l4363.

3. Boutitie F, Pinede L, Schulman S, et al. Influence of preceding length of anticoagulant treatment and initial presentation of venous thromboembolism on risk of recurrence after stopping treatment: analysis of individual participants’ data from seven trials. BMJ. 2011;342:d3036.

4. Couturaud F, Sanchez O, Pernod G, et al. Six months vs extended oral anticoagulation after a first episode of pulmonary embolism: the PADIS-PE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(1):31-40.

5. Kovacs MJ, Kahn SR, Wells PS, et al. Patients with a first symptomatic unprovoked DVT are at higher risk of recurrent VTE than patients with a first unprovoked PE. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(9):1926-1932.

6. Baglin T, Douketis J, Tosetto A, et al. Does the clinical presentation and extent of venous thrombosis predict likelihood and type of recurrence? A patient level meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(11):2436-2442.

7. Linkins LA, Choi PT, Douketis JD. Clinical impact of bleeding in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):893-900.

8. van der Wall SJ, van der Pol LM, Ende Verhaar YM, et al. Fatal recurrent VTE after anticoagulant treatment for unprovoked VTE: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27(150):180094.

9. Adelhelm JBH, Christensen R, Balbi GGM, Voss A. Therapy with direct oral anticoagulants for secondary prevention of thromboembolic events in the antiphospholipid syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lupus Sci Med. 2023;10(2):e001018.

10. Ridker PM, Goldhaber SZ, Danielson E, et al. Long-term, low-intensity warfarin therapy for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(15):1425-1434.

11. Kearon C, Ginsberg JS, Kovacs MJ, et al. Comparison of low-intensity warfarin therapy with conventional-intensity warfarin therapy for long-term prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(7):631-639.

12. Becattini C, Agnelli G, Schenone A, et al. Aspirin for preventing the recurrence of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1959-1967.

13. Brighton TA, Eikelboom JW, Mann K, et al. Low-dose aspirin for preventing recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1979-1987.

14. Simes J, Becattini C, Agnelli G, et al. Aspirin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism: the INSPIRE collaboration. Circulation. 2014;130(13):1062-1071.

15. Andreozzi GM, Bignamini AA, Davì G, et al. Sulodexide for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism: the sulodexide in secondary prevention of recurrent deep vein thrombosis (SURVET) study: a multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation. 2015;132(20):1891-1897.

16. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Apixaban for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(8):699-708.

17. Weitz JI, Lensing AWA, Prins MH, et al. Rivaroxaban or aspirin for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(13):1211-1222.

18. Prins MH, Lensing AWA, Prandoni P, et al. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism according to baseline risk factor profiles. Blood Adv. 2018;2(7):788-796.

19. Rodger MA, Kahn SR, Wells PS, et al. Identifying unprovoked thromboembolism patients at low risk for recurrence who can discontinue anticoagulant therapy. CMAJ. 2008;179(5):417-426.

20. Eichinger S, Heinze G, Jandeck LM, Kyrle PA. Risk assessment of recurrence in patients with unprovoked deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism: the Vienna prediction model. Circulation. 2010;121(14):1630-1636.

21. Douketis J, Tosetto A, Marcucci M, et al. Risk of recurrence after venous thromboembolism in men and women: patient level meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d813.

22. Franco Moreno AI, García Navarro MJ, Ortiz Sánchez J, et al. A risk score for prediction of recurrence in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism (DAMOVES). Eur J Intern Med. 2016;29:59-64.

23. Rodger MA, Le Gal G, Anderson DR, et al. Validating the HERDOO2 rule to guide treatment duration for women with unprovoked venous thrombosis: multinational prospective cohort management study. BMJ. 2017;356:j1065.

24. Aziz D, Skeith L, Rodger MA, et al. Long-term risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after a first contraceptive-related event: data from REVERSE cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19(6):1526-1532.

25. Palareti G, Cosmi B, Legnani C, et al. D-dimer to guide the duration of anticoagulation in patients with venous thromboembolism: a management study. Blood. 2014;124(2):196-203.

26. Prandoni P, Vedovetto V, Ciammaichella M, et al. Residual vein thrombosis and serial D-dimer for the long-term management of patients with deep venous thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2017;154:35-41.

27. Palareti G, Poli D, Ageno W, et al. D-dimer and reduced-dose apixaban for extended treatment after unprovoked venous thromboembolism: the Apidulcis study. Blood Adv. 2022;6(23):6005-6015.

28. Palareti G, Legnani C, Tosetto A, et al. D-dimer and risk of venous thromboembolism recurrence: comparison of two studies with similar designs but different laboratory and clinical results. Thromb Res. 2024;238:52-59.

29. Xu Y, Khan F, Kovacs MJ, et al. Serial D-dimers after anticoagulant cessation in unprovoked venous thromboembolism: data from the REVERSE cohort study. Thromb Res. 2023;231:32-38.

30. Khan F, Tritschler T, Kimpton M, et al. Long-term risk for major bleeding during extended oral anticoagulant therapy for first unprovoked venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(10):1420-1429.

31. de Winter MA, Büller HR, Carrier M, et al. Recurrent venous thromboembolism and bleeding with extended anticoagulation: the VTE-PREDICT risk score. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(14):1231-1244.

32. Wells PS, Tritschler T, Khan F, et al. Predicting major bleeding during extended anticoagulation for unprovoked or weakly provoked venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2022;6(15):4605-4616.

33. Prandoni P, Bilora F, Mahé I, et al. The value of the CHAP model for prediction of the bleeding risk in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism: findings from the RIETE registry. Thromb Res. 2023;224:17-20.

34. Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-e496S.

35. Prandoni P, Gabara C, Bilora F, et al. Age over 75 does not increase the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism: findings from the RIETE registry. Thromb Res. 2023;222:16-19.

36. Takahashi K, Yamashita Y, Morimoto T, et al. Age and long-term outcomes of patients with venous thromboembolism: from the COMMAND VTE Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2023;383:89-95.