Combination therapy in the treatment of varices

Craig BROWN MD, MS1;

Christopher O. AUDU MD, PhD1;

Danielle C. SUTZKO MD, MS2;

Andrea T. OBI MD1;

Thomas W. WAKEFIELD MD1

1Section of Vascular Surgery, Department

of Surgery, Michigan Medicine;

2Division of Vascular Surgery and

Endovascular Therapy, Department

of Surgery, University of Alabama

at Birmingham

Abstract

Background: There is significant variation in the treatment of combined truncal-vein reflux and symptomatic varicosities. We sought to use the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) Varicose Vein Registry (VVR) to explore the contemporary real-world experience of combined ablation and phlebectomy versus ablation alone. Methods: Using the VQI/VVR database, patients undergoing combined ablation and phlebectomy and ablation alone were identified between January 2015 and December 2018. Using propensity-score matching on age; gender; race; history of deep venous thrombosis (DVT); previous venous surgery; anticoagulation therapy; pre-op clinical, etiology, anatomy and pathophysiology (CEAP) classification; truncal-vein location; and surgical setting, patients undergoing combined treatment were matched with those undergoing truncal ablation alone. Univariate descriptive statistics of demographic and procedural data were performed before and after matching. Change in venous clinical severity score (VCSS), patient-reported outcomes (PROs), and complications were compared between groups after matching using logistic regression, and average treatment effects were reported.Results: 10 952 patients were identified on initial query of VQI/VVR, including 5979 patients who underwent combined ablation and phlebectomy and 4973 patients who underwent ablation alone. After matching, the cohort included 3348 combined-treatment patients and 3309 ablation only patients. There were minimal differences in demographics or preoperative characteristics after matching. After matching, there were significantly greater improvements in both the VCSS (1.6 points greater improvement) and PROs for those receiving combined ablation and phlebectomy than with ablation alone. Systemic complications were rare. After matching, there were statistically higher rates of hematoma (0.9%) and paresthesias (2.1%) for combined treatment than with ablation alone. There was no statistically significant difference in the rates of DVT, bleeding, blistering, pigmentation, phlebitis, ulcer formation, wound infection, or endovenous heat-induced thrombosis (EHIT). Conclusions: Patients frequently undergo combined treatment of truncal reflux and varicosities. Combined treatment is associated with a significantly higher improvement in VCSS and PROs than ablation alone, even after matching for preoperative disease severity and risk factors. Combined procedures are associated with a slightly higher risk of post-op hematoma and paresthesias. These results suggest that combined treatment of reflux and varicosities may result in higher treatment satisfaction with minimal increased risk to patients than ablation alone.

Introduction

Varicose veins are a common manifestation of chronic venous insufficiency, affecting about 25% of adults in the Western hemisphere.1,2 Superficial venous disease can present symptomatically as pain, itching, and irritation over the veins themselves, and be associated with heaviness, swelling, and achiness, leading to a diminished quality of life.1 Conservative management, including exercise and the use of compression stockings, may provide symptomatic relief. However, definitive treatment involves not only the treatment of symptomatic varicose veins, but also the treatment of the underlying axial reflux. The treatment of combined axial reflux and symptomatic varicose veins can be approached with either a staged or combined approach (ablation and phlebectomy).

There is significant variation across venous practitioners’ approach to patients with symptomatic varicose veins and axial reflux. Previous evidence has been limited to small clinical trials and case series with conflicting results. The four prospectively collected randomized clinical trials that have compared staged and combined ablation/phlebectomy enrolled less than 500 patients in total in all trials combined, often in single centers.3-6 These trials all demonstrated significantly improved quality of life among patients undergoing combined treatment, and three demonstrated a significantly improved venous clinical severity score (VCSS).3-5 Other data from nonrandomized studies, however, have suggested that patients treated with ablation may not necessarily go on to require phlebectomy.7-9 Given the lack of clear evidence, guidelines have not definitively endorsed either strategy of combined or staged treatments. Recently, the Society for Vascular Surgery and American Venous Forum published Appropriate Use Criteria for venous disease and concluded that “Providing care for the diseased tributaries of an ablated saphenous vein either concomitantly or as a staged procedure is appropriate.”10

Within this context, we sought to use the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) Varicose Vein Registry (VVR) to explore the contemporary real-world experience of combined ablation and phlebectomy versus ablation alone. We hypothesized that patients undergoing combined ablation and phlebectomy would have significantly greater improvements in VCSS and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in the short term with minimal differences in complications compared with ablation alone.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board for the Human Research Protection Program at the University of Michigan approved this retrospective study (HUM0114502) as exempt, and informed consent was waived.

The VQI VVR is a prospectively collected registry of patients treated surgically for superficial venous disease. Within this registry, trained staff at each center collect patient demographic, diagnostic, preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data prospectively.11-14 This is a voluntary registry, and center participation is not required. To maintain consistent data integrity, several approaches are taken. Training webinars are used to educate data managers. There are accessible online support staff to answer questions. Data abstraction and all definitions are uniform across the database. An audit of hospital claims is used to ensure consecutive procedures are being entered by participating centers. All online VQI data forms have been augmented with error tracking software to avoid erroneous entry. Additionally, statistical tests are used to identify any data entry errors and these errors are manually reviewed with centers to ensure data integrity and accuracy.

The VQI VVR from January 2015 through December 2018 was queried specifically, identifying all patients who underwent treatment for venous insufficiency. Inclusion criteria included patients with symptomatic venous disease (C2-C5) who underwent procedures to ablate truncal veins (including the great saphenous vein, anterior accessory great saphenous vein, superficial accessory great saphenous vein, small saphenous vein, and other truncal vein) using either radiofrequency ablation or laser. We excluded patients who underwent procedures from 2014 because they had been entered into the registry retrospectively. To investigate the effect of combined ablation and phlebectomy, we excluded patients who underwent sclerotherapy to decrease confounding and selection bias. Follow-up within the registry occurred at an early (0-3 months) and late (>3 months) time period. Complications were analyzed at early follow-up, whereas outcomes (including VCSS, CEAP, and PROs) were analyzed at late follow-up (typically 3-12 months).

The VQI VVR includes not only the CEAP and VCSS score before surgery and post operatively, but also a detailed vein-specific quality of life survey (PRO score). This PRO score is based upon the previously validated Varicose Vein Symptom Questionnaire (VVSimQ)15-16 with an expansion of measures to include the impact on work. This PRO score measures venous quality of life, specifically symptoms of i) heaviness, ii) achiness, iii) swelling, iv) throbbing, v) itching, vi) appearance, and vii) impact on work/activity. PROs are rated on a scale of 0-4 or 5 depending upon the variable. For the variables heaviness, achiness, swelling, throbbing, and itching, the scale was: 0, none of the time; 1, a little of the time; 2, some of the time; 3, a good bit of the time; 4, most of the time; and 5, all of the time. For appearance, the scale was: 0, not at all noticeable; 1, slightly noticeable; 2, moderately noticeable; 3, very noticeable; and 4, extremely noticeable. For impact on work/activity, the scale was: 0, none; 1, symptoms but full work/activity; 2, mildly reduced work/activity; 3, moderately reduced work/activity; 4, severely reduced work/activity; and 5, unable to do work/ activity. The total PRO score could reach as high as 34.

Procedure-related complications are reported on the VQI VVR at initial (early) follow-up and include bleeding requiring re-intervention, skin blistering, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), proximal thrombus extension (endovenous heat-induced thrombosis, EHIT), hematoma, paresthesia, pigmentation, superficial phlebitis, ulceration, and infections. Systemic complications are also reported in the VQI VVR at early follow-up, including allergic reaction, migraine, visual disturbance, cough/chest tightness, systemic infection, pulmonary embolism, transient ischemic attack, stroke, and death.

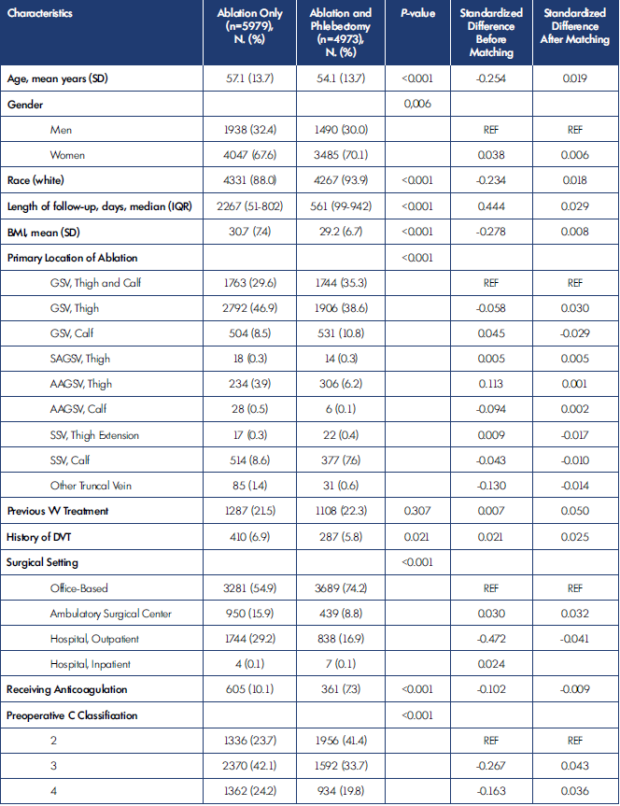

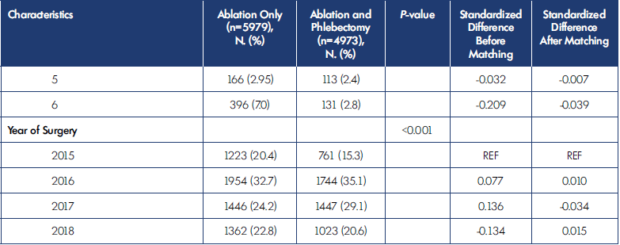

Univariate analysis was used to evaluate patient demographics and procedural data using the Student t-test for continuous variables, X2 for categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney for nonparametric measures. To better control for the differences in presentation, a propensityscore– matching strategy was employed. A propensity score was generated using age, gender, race, prior venous procedure, history of DVT, anticoagulation, truncal vein location, CEAP classification, and setting. Propensityscore matching was performed using STATA 14 TEFFECTS PSMATCH with a nearest neighbor 1:1 matching without replacement and a caliper of 0.05. After matching patients, the cohorts were compared on the basis of the standardized differences before and after matching to assess the adequacy of matching. Matching resulted in minimal differences between study populations (as shown in Table I). Next, the matched study cohorts were compared via logistic regression, and differences in outcomes between study cohorts were estimated on the basis of the average treatment effects. Average treatment effects represent a statistical test that is employed to compare the estimate effect of treatment on outcomes. Statistical significance was set at a P-value <0.05. We performed all statistical analyses with Stata version 15.0 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas).

Results

A total of 10 952 patients were identified on initial query of VQI/VVR, including 5979 patients who underwent combined ablation and phlebectomy and 4973 patients who underwent ablation alone. After matching, the cohort included 3348 combined-treatment patients and 3309 ablation-only patients. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in Table I. After matching, patients were well-matched for all variables, except for surgical setting. Combined-treatment patients were more likely to be treated in an office-based setting as opposed to an ambulatory surgical center or outpatient hospital setting. Before matching, there were significant differences in the C classification among patients undergoing combined ablation and phlebectomy versus ablation alone; however, after matching, these differences were significantly attenuated.

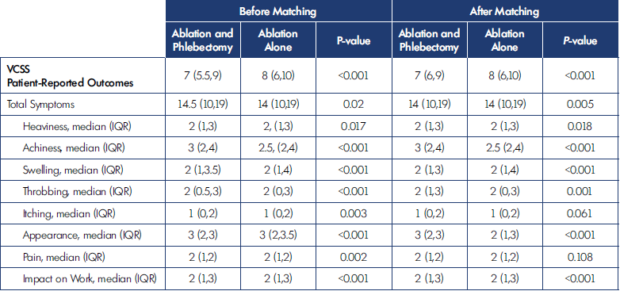

Preoperative disease severity was also assessed using the VCSS and PROs (Table II). Before matching, the VCSS score was significantly higher among patients undergoing ablation alone than with combined ablation and phlebectomy. In contrast, there was slightly higher severity of patient-reported symptoms (PROs) among patients undergoing combined ablation and phlebectomy than with phlebectomy alone. Importantly, after matching, these differences persisted.

AAGSV, anterior accessory great saphenous vein; BMI, body mass index; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; GSV, great saphenous vein; IQR, interquartile

range; SAGSV, superficial accessory great saphenous vein; SD, standard deviation; SSV, small saphenous vein; REF, reference; VV, varicose vein.

Table I. Patient and procedure characteristics before and after matching.

IQR, interquartile range; VCSS, venous clinical severity score.

Table II. Preoperative venous clinical severity score (VCSS) and patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

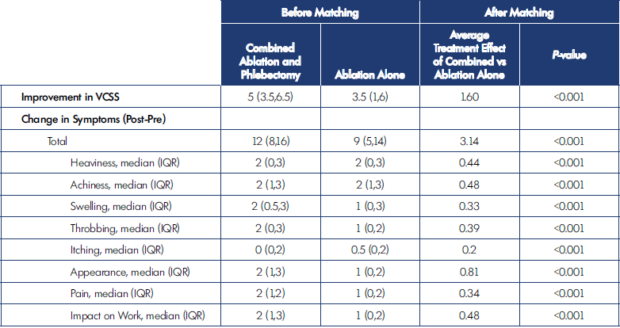

There were significantly greater improvements in both the VCSS and PROs with combined ablation and phlebectomy than with ablation alone (Table III). Before matching, the change in VCSS was a median of 5 among patients undergoing combined ablation and phlebectomy compared with 3.5 among patients undergoing ablation alone. Similarly, the total improvement in symptoms (PROs) was 12 among patients undergoing ablation as compared to 9 among patients undergoing ablation alone. The individual PROs are shown in Table III. After propensity-score matching, the differences between combined ablation and phlebectomy and ablation alone persisted for both VCSS improvement and improvement in PROs.

The average treatment effect of combined treatment was 1.6, meaning that combined ablation and phlebectomy results in a greater average improvement in VCSS of 1.6 points more than ablation alone. Similarly, among the total symptom score (PRO), the average improvement was 3.14 points after matching. This means that patients undergoing ablation and phlebectomy on average have a more than 3-point greater improvement in symptoms than with ablation alone. The individual improvements in the PROs are shown in Table III.

IQR, interquartile range; VCSS, venous clinical severity score.

Table III. Improvement in venous clinical severity score (VCSS) and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) after combined ablation and

phlebectomy versus ablation alone.

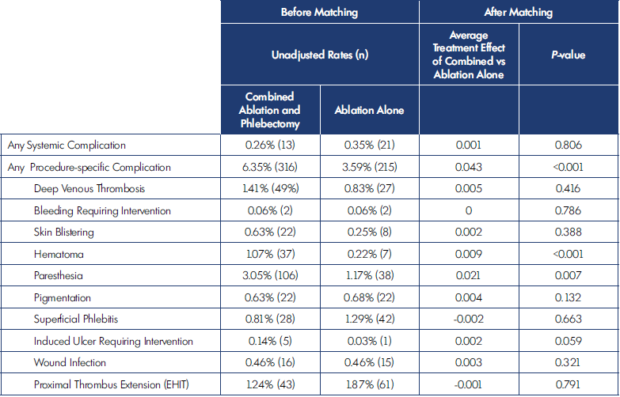

Complications after combined ablation and phlebectomy compared with ablation alone are shown in Table IV. Systemic complications in all groups were very rare. Within both the combined and ablation-only cohorts, the total incidence of systemic complications was 0.31% (34 patients) and no significant differences were detected (0.35% vs 0.26%; P=0.401). Of these complications, there was 1 systemic infection, 2 pulmonary embolisms (PEs), and no episodes of transient ischemic attack (TIA)/ stroke or death. Given the low frequency, no further comparisons were performed. Before matching, combined therapy compared with ablation-only treatment of venous insufficiency and varicose veins was associated with an increased incidence of hematoma (1.07% vs 0.22%; P<0.001), and paresthesias (3.05% vs 1.17%; P<0.001). Combined therapy was associated with a statistically significant decreased incidence of EHIT (1.24% vs 1.87%; P=0.038). Other factors, including bleeding, DVT, pigmentation, phlebitis, ulceration, and infection were not statistically significantly different between the two groups (Table IV).

After propensity-score matching, the average treatment effect of combined ablation and phlebectomy was calculated for each outcome (Table IV). Comparing the effect of combined treatment with ablation alone, patients undergoing combined ablation and phlebectomy had a 0.9% increased rate of hematoma as compared with patients undergoing ablation alone (average treatment effect of 0.009). Similarly, after matching, the difference in paresthesias remained; the average treatment effect of combined ablation and phlebectomy was a 2.1% higher rate of paresthesias than in patients undergoing ablation alone. After propensity-score matching, there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of DVT, bleeding, blistering, pigmentation, phlebitis, ulcer formation, wound infection, or EHIT.

Discussion

There is a lack of consensus about the timing and approach to treating patients with axial reflux and symptomatic varicose veins. Our analysis, using the robust and large sample size of the VQI VVR, demonstrates that combined ablation and phlebectomy is associated with greater improvement in both VCSS and PROs, with low rates of complications. Importantly, although both combined ablation- and-phlebectomy and ablation-alone patients experienced improvements in their symptoms (PROs), patients experienced greater improvements in all symptoms when undergoing a combined procedure as opposed to ablation alone. This analysis not only used the largest sample to compare these groups, but also employed propensity-score matching to minimize the confounding from measured covariates, including C classification (CEAP). This data supports the ongoing treatment of superficial venous disease with a combined approach.

EHIT, endovenous heat-induced thrombus.

Table IV. Complications after ablation and phlebectomy versus ablation alone.

Previous work has suggested the superiority of a combined approach. Hager et al,17 in a recent review of the literature, identified the relative advantages of a combined approach, including a single anesthetic, fewer visits, and easier scheduling. There are several randomized controlled clinical trials that have been performed comparing combined and staged procedures for the treatment of venous disease. The AVULS trial (Ambulatory Varicosity Avulsion Later or Synchronized) randomized 101 patients to either combined ablation and phlebectomy or delayed phlebectomy after ablation.4 Importantly, this trial demonstrated no major differences in complications and significantly greater VCSS improvement and Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire score (AVVQ) improvement at early follow-up. Importantly, these differences in the PROs using the AVVQ were not significant in longer follow-up beyond 6 weeks (Lane et al4 2015). Similarly, El-Sheikha et al5 randomized 50 patients to receive either combined ablation and phlebectomy or ablation and staged phlebectomy and followed outcomes for 5 years. Patients undergoing combined procedures had greater improvement in VCSS and AVVQ scores at 12 weeks. These differences converged by 1 year of follow-up and were no longer statistically significant.5 Carradice et al,3 in another small randomized controlled trial, compared combined endovenous laser therapy (EVLT) and phlebectomy with EVLT alone. This study also demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in VCSS and AVVQ at the early follow-up (3 months) that attenuated over time and was no longer significant by 1-year follow-up. The authors noted that two-thirds of the patients in the EVLT-alone arm required staged phlebectomy in followup as compared with only one patient among the combined EVLT and phlebectomy group who required an additional procedure.3 These small randomized clinical trials were limited by small sample size and the single center design, limiting the generalizability of these trials. More recently, others have reported analyses of venous registries examining this question. In a recent analysis of the American Venous Forum Varicose Vein Module of the American Venous Registry, Conway and colleagues18 compared combined ablation and phlebectomy with ablation alone. This analysis included a larger sample size of 526 patients over a 5-year period, of which more than 80% of patients had milder disease (C2). The authors reported that patients undergoing a combined procedure had a greater improvement in VCSS at both 1-month and 6-month follow-up.18

Our analysis adds to the body of literature supporting the use of combined ablation and phlebectomy as a safe and effective treatment strategy for symptomatic varicose veins. Importantly, when compared with ablation alone, we have demonstrated that patients undergoing combined procedures have a significantly greater improvement in both VCSS and PROs. We did not, however, directly compare patients undergoing combined ablation and phlebectomy with staged ablation and phlebectomy. Such an analysis is difficult in the current database construction of the VQI VVR. Additionally, several previous studies have raised the question of the necessity for phlebectomy after a successful ablation.19 After ablation of the axial reflux, varicose veins have been shown to significantly improve with as much as 42% of varicosities resolving above the knee and 25% below the knee.7 Importantly, our analysis was not designed to assess the long-term risk of reintervention for varicose veins in patients undergoing ablation alone.

Additionally, there are some important limitations inherent to the design of the study and database used. The VQI VVR is a voluntary registry that may not be representative of all practices and patient populations. The surgical approach, including ablation methods, and individual surgeon bias will influence the choice of procedure. Similarly, this study utilized a propensity-score analysis to adjust for measured confounders, but it cannot adjust for unmeasured confounder or bias. Additionally, the outcomes can be reported over a variable time frame of 3 to 12 months, and previous studies have shown that the effect of varicose vein treatment attenuates over time. Without a consistent time for measuring the PROs and VCSS, this may lead to an underestimation of the effect of both treatments. Nevertheless, this analysis supports our hypothesis that in patients with truncal superficial vein reflux and symptomatic varicose veins, combination ablation and phlebectomy results in improved provider-measured results and PROs, with minimal risk of complications.

Conclusion

The results of this study add to the body of evidence that combined ablation and phlebectomy is a safe and effective treatment strategy for patients suffering from axial reflux and symptomatic varicose veins. This real-world multicenter analysis demonstrates that combined treatment is associated with greater improvement in both VCSS and quality of life (PROs), while also experiencing remarkably low rates of complications. Additional work is necessary to compare the outcomes of combined ablation and phlebectomy with planned staged ablation and phlebectomy.

REFERENCES

1. Carpentier PH, Maricq HR, Biro C, Ponçot-Makinen CO, Franco A. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical patterns of chronic venous disorders of lower limbs: a population-based study in France. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40(4):650- 659. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2004.07.025.

2. Beebe-Dimmer JL, Pfeifer JR, Engle JS, Schottenfeld D. The epidemiology of chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(3):175-184. doi:10.1016/j. annepidem.2004.05.015.

3. Carradice D, Mekako AI, Hatfield J, Chetter IC. Randomized clinical trial of concomitant or sequential phlebectomy after endovenous laser therapy for varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2009;96(4):369-375. doi:10.1002/ bjs.6556.

4. Lane TRA, Kelleher D, Shepherd AC, Franklin IJ, Davies AH. Ambulatory varicosity avulsion later or synchronized (AVULS). Ann Surg. 2015;261(4):654-661. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000790.

5. El-Sheikha J, Nandhra S, Carradice D, et al. Clinical outcomes and quality of life 5 years after a randomized trial of concomitant or sequential phlebectomy following endovenous laser ablation for varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2014;101(9):1093-1097. doi:10.1002/ bjs.9565.

6. Harlander-Locke M, Jimenez JC, Lawrence PF, Derubertis BG, Rigberg DA, Gelabert HA. Endovenous ablation with concomitant phlebectomy is a safe and effective method of treatment for symptomatic patients with axial reflux and large incompetent tributaries. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(1):166-172. doi:10.1016/j. jvs.2012.12.054.

7. Monahan DL. Can phlebectomy be deferred in the treatment of varicose veins? J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(6):1145- 1149. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2005.08.034.

8. Kim HK, Kim HJ, Shim JH, Baek MJ, Sohn YS, Choi YH. Endovenous lasering versus ambulatory phlebectomy of varicose tributaries in conjunction with endovenous laser treatment of the great or small saphenous vein. Ann Vasc Surg. 2009;23(2):207-211. doi:10.1016/j. avsg.2008.05.014.

9. Schanzer H. Endovenous ablation plus microphlebectomy/sclerotherapy for the treatment of varicose veins: single or two-stage procedure? Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2010;44(7):545- 5549. doi:10.1177/1538574410375126.

10. Masuda E, Ozsvath K, Vossler J, et al. The 2020 appropriate use criteria for chronic lower extremity venous disease of the American Venous Forum, the Society for Vascular Surgery, the American Vein and Lymphatic Society, and the Society of Interventional Radiology. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(4):505-525.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.02.001.

11. Sutzko DC, Obi AT, Kimball AS, Smith ME, Wakefield TW, Osborne NH. Clinical outcomes after varicose vein procedures in octogenarians within the Vascular Quality Initiative Varicose Vein Registry. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6(4):464-470. doi:10.1016/j.jvsv.2018.02.008.

12. Sutzko DC, Andraska EA, Obi AT, et al. Age is not a barrier to good outcomes after varicose vein procedures. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017;5(5):647-657.e1. doi:10.1016/j. jvsv.2017.04.013.

13. Obi AT, Reames BN, Rook TJ, et al. Outcomes associated with ablation compared to combined ablation and transilluminated powered phlebectomy in the treatment of venous varicosities. Phlebology. 2016;31(9):618-624. doi:10.1177/0268355515604257.

14. Brown CS, Obi AT, Cronenwett JL, Kabnick L, Wakefield TW, Osborne NH. Outcomes after truncal ablation with or without concomitant phlebectomy for isolated symptomatic varicose veins (C2 disease). J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;S2213-333X(20)30324-3. doi:10.1016/j.jvsv.2020.05.016.

15. Paty J, Turner-Bowker DM, Elash CA, Wright D. The VVSymQ_ instrument: use of a new patient-reported outcome measure for assessment of varicose vein symptoms. Phlebology. 2016;31(7):481- 488. doi:10.1177/0268355515595193.

16. Paty J, Elash CA, Turner-Bowker DM. Content validity for the VVSymQ_ instrument: a new patient-reported outcome measure for the assessment of varicose veins symptoms. Patient. 2017;10(1):51-63. doi:10.1007/s40271- 016-0183-y.

17. Hager ES, Ozvath KJ, Dillavou ED. Evidence summary of combined saphenous ablation and treatment of varicosities versus staged phlebectomy. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017;5(1):134-137. doi:10.1016/j. jvsv.2016.07.009.

18. Conway RG, Almeida JI, Kabnick L, Wakefield TW, Buchwald AG, Lal BK. Clinical response to combination therapy in the treatment of varicose veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(2):216-223. doi:10.1016/j. jvsv.2019.10.015.

19. Welch HJ. Endovenous ablation of the great saphenous vein may avert phlebectomy for branch varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(3):601-605. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2006.06.003.