Controversies surrounding symptoms and signs of chronic venous disorders

symptoms and signs of chronic

venous disorders

Department of Nursing,

Ruda Śląska,

Poland

Abstract

Association of so-called venous symptoms (aching, itching, tingling, burning sensation, swelling, easily fatigued legs, leg heaviness, and leg restlessness) with chronic venous disease (CVD) still remains a controversial issue. Although these symptoms and a decreased quality of life are common in patients with venous incompetence, and are even more frequent in those with a history of venous thrombosis and/or recurrent and bilateral varicose veins, research has actually revealed that these complaints are poorly correlated with objective signs of venous insufficiency. A venous source for these complaints is obvious in patients with advanced CVD, but a substantial part of venous symptoms, especially in patients with telangiectasias and uncomplicated varicose veins, is actually not of venous origin. In addition, such symptoms can be reported by many patients presenting with nonvenous diseases, while uncomplicated varicose veins can cause few symptoms or be asymptomatic. In many venous patients, these symptoms are not permanent, but can only be seen at the end of the day. Therefore, it is important to consider and investigate an alternative cause of such “venous” complaints, especially because other pathologies can accompany CVD and produce similar symptoms. The most common pathologies that may be responsible and should be taken into account include spinal disc herniation, hip and knee arthrosis, peripheral arterial disease, joint and ligament overload due to obesity, peripheral neuropathy, and adverse drug reactions.

Introduction

There is a great deal of controversy surrounding the association of so-called venous symptoms with chronic venous disease (CVD). An uncertain association of the presence of uncomplicated varicosities with these symptoms has even lead some health care providers to restrict access to treatment for asymptomatic patients with varicose veins or those experiencing few symptoms.1 Clinical symptoms that are thought to be caused by chronic venous insufficiency include aching leg pain, itching, tingling, burning sensation, swelling, easily fatigued legs, leg heaviness, and restlessness. These symptoms typically worsen as the day progresses.2 The presence of such complaints usually correlates with a decreased quality of life (QOL). An association of these symptoms with CVD is not as obvious as is usually believed. While some researchers found significant correlations between venous symptoms and the signs of CVD(venous reflux revealed by means of Doppler sonography, visible varicose veins, or skin changes typical for venous incompetence [hyperpigmentation, lipodermatosclerosis, and ulcers]), others argued that these symptoms poorly correlated with clinical signs of venous insufficiency. In this review, I will summarize the research related to this problem in an attempt to explain conflicting results and interpretations of the studies.

Correlating symptoms and signs

Severe chronic venous disease

The majority of patients with severe forms of CVD–those with leg edema (C3 according to the clinical, etiological, anatomical, pathophysiological [CEAP] classification), skin changes (C4), and venous ulcers (C5 and C6)–present with some of the above symptoms. The proportion of patients with venous symptoms significantly increases with the “C” class of the CEAP classification.3 Usually, in patients with advanced CVD, an association of venous symptoms with venous incompetence is not questioned, even if other pathologies can accompany chronic venous insufficiency and may produce similar symptoms. Also, it has been demonstrated that these patients present with a decreased QOL, with progressive impairment in QOL from C3 to C5/C6.2,4,5

Less severe chronic venous disease

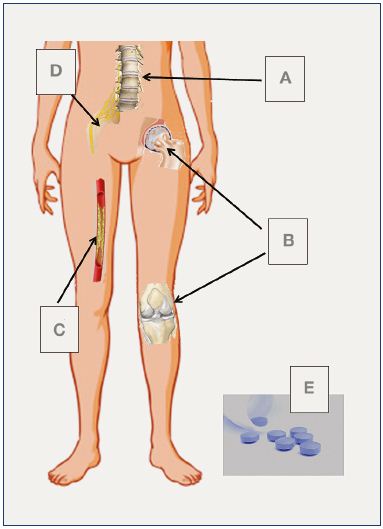

Venous background of clinical symptoms in patients with less severe forms of CVD, C1 and C2, remains controversial. Many of these patients are asymptomatic despite the presence of an obvious venous pathology.3,6-10 In many C1/C2 patients, these complaints may actually be rooted in another coexisting pathology, such as osteoarticular, neurological, or arterial pathology (Figure 1). For example, in the VEINES study (VEnous INsufficiency Epidemiologic and economic Study; 1531 patients with CVD and 1313 controls were assessed), the authors did not find significant differences in venous symptoms between the controls and patients with varicose veins (C2). Thus, the authors speculated that clinical symptoms in patients with varicose veins probably resulted from concomitant aspects of CVD and not from varicosities per se.9

Poor correlation between symptoms and signs

In the Edinburgh Vein Study, a cross-sectional population study that assessed 1566 individuals, the authors did not demonstrate an association between lower-limb symptoms (leg heaviness, aching, and itching) and the presence of visible varicose veins.11 Nor did they reveal a significant correlation between venous reflux and lower-limb symptoms.12 Consequently, they concluded that most of these symptoms probably had a nonvenous cause.11

A similar conclusion came from another study, where itching and burning sensations in the legs were not correlated with the severity of venous insufficiency.13 Also, an observational study by Howlader et al that assessed 132 patients attending a vascular clinic, did not reveal an association between the severity of symptoms and anatomic distribution of venous reflux.14

Potential correlation between symptoms and signs

In the San Diego population study, a cross-sectional study that assessed 2209 individuals, the researchers revealed an association between clinical symptoms and the presence of venous disease. Leg edema was the most specific symptom related to venous incompetence. Other symptoms (eg, leg heaviness, aching, and itching), although more common in the patients with venous disease, were also found (5% to 15%) in individuals without CVD.15

Figure 1. The most common nonvenous causes of the so-called

“venous” symptoms.

A, Spinal disc herniation; B, hip and knee arthrosis; C, peripheral

arterial disease; D, peripheral neuropathy; E, drug adverse

reactions (calcium channel blocker or other medications).

Similar results were demonstrated in a recent Dutch study.2 Except for swelling of the leg and itching, the authors revealed small and nonsignificant differences in the prevalence of venous symptoms between the patients with CVD and those suffering from other pathologies (eg, arthrosis, peripheral arterial disease, or spinal disc herniation). However, the patients with venous incompetence were more likely to experience symptoms at the end of the day, which was atypical in patients with other pathologies.2

In the recently published Bonn Vein Study 1, leg symptoms were more prevalent in subjects with varicose veins or chronic venous insufficiency, which was demonstrated using sonography. These symptoms were also more frequent in obese and underweight individuals. Some symptoms, ie, itching, leg heaviness, tightness, swelling, and pain after standing or sitting, were particularly associated with venous disease.16

In another study, the researchers found venous symptoms more frequently among patients with telangiectasias, and even more in patients with varicose veins. However, a substantial proportion of the individuals without venous disease also reported “venous” complaints (heaviness, swelling, aching, restless legs, cramps, itching, and tingling) and differences between the subjects with no visible venous pathology and those with either telangiectasias or varicose veins were modest.17

Similar conclusions also came from another survey. The authors of this cross-sectional study revealed venous symptoms in 60% of patients with varicose veins and demonstrated that this association was statistically significant. However, 33% of patients without varicose veins also suffered from venous symptoms. Risk factors that were significantly associated with these symptoms included prolonged sitting or standing and a history of thromboembolism. These symptoms were more common in older women and in tall (height >175 cm) and overweight (body mass index [BMI] >25 kg/m2) men. Consequently, the authors concluded that varicose veins were not the only cause of venous symptoms. Other factors, primarily prolonged sitting and standing, could be a source of such symptoms, and improper clothes and shoes may also play a role. Of note, the researchers did not demonstrate a statistically significant correlation between these symptoms and a history of osteoarthritis. Still, venous symptoms were more common in such patients (20% vs 15% in patients with a negative history of osteoarthritis). Notably, in this study, the patients were not clinically examined to reveal an osteoarticular pathology.8

In another cross-sectional study on clinical features of CVD in 16 251 Italian patients, the researchers found a statistically significant positive correlation between the symptoms (eg, tired and heavy legs, leg pain, or leg edema) and severity of the venous disease (defined by the “C” grade of the CEAP classification). These venous symptoms were more prevalent in women and in patients with an increased BMI. However, almost all participants of this survey reported some complaints and only about 10% of the individuals surveyed were free of venous symptoms. An actual venous background of these complaints in the population studied remains questionable. Moreover, it was likely that relevant selection bias occurred in this study, since the individuals attending this survey were attracted by means of advertising in mass media. Therefore, the population was probably skewed toward people with some leg complaints that were not necessarily of a vascular origin.10 To add to the confusion, in one study, patients with benign venous disease (C2/C3) reported more symptoms than those with complicated varicose veins (C4/C5).14

Venous background of leg symptoms in patients with telangiectasias and small epifascial veins (C1) is even less certain. In a cross-sectional study that evaluated the clinical impact of small cutaneous veins, researchers found that venous symptoms, comprising leg edema, muscle cramps, and restless legs, were more common in patients with small varicosities in comparison with healthy controls (C0), except for itching, which was less prevalent in individuals with dilated veins. However, when adjusted for age and sex, these differences–except for leg swelling–were no longer statistically significant. Thus, the authors concluded that although venous symptoms were quite common, even in C1 patients, patients’ age (older subjects) and sex (women) seemed to be a better explanation for these complaints than the presence of small cutaneous varicosities. Leg swelling can be related to dilated veins; however, their clinical relevance in the development of leg swelling seemed to be low (odds ratio, 1.3).18

Chronic venous disease and quality of life

Clinical stage

There are also conflicting results for studies on QOL in early stages of CVD. In the San Diego population study, the presence of venous disease, even of uncomplicated varicose veins, was associated with significant limitations on all functional scales (eg, physical functioning, role functioning, pain, and general health perception) of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) QOL questionnaire.5 In another study, female sex was associated with a worse QOL in the patients referred to the varicose vein clinic, but this effect was no longer observed when only C2 patients were analyzed.7 Similarly, the VEINES study did not reveal significant differences in QOL between C2 patients and controls,9 and there was no association between the “C” class and QOL impairment in a study assessing patients qualified for surgical treatment of varicose veins.7 Also, an observational study on patients assessed in vascular laboratories did not demonstrate a decreased QOL in the C1 and C2 patients. Some QOL scores were even higher in varicose vein patients than in healthy people.4,19 Likewise, in a study evaluating patients qualified for invasive varicose vein treatment, the authors found that an impaired QOL was independent of the clinical stage of venous disease.20 However, a similar cross-sectional study (570 venous patients from Serbia) revealed a progressive worsening of QOL from C1 to C6. Even those patients presenting with C1 and C2 classes reported an impairment in QOL and did not consider their venous incompetence as a benign cosmetic problem, but rather as a real disease.21 In another study, worsening QOL was also found in C3 to C6 patients as compared with the C1 and C2 patients.22

Venous reflux and inflammatory markers

Similarly, a correlation between the degree of venous reflux and QOL reduction is uncertain. Although it is expected that profound venous reflux or an increased diameter of the incompetent saphenous trunk would be associated with more severe clinical symptoms and decreased QOL, research does not always confirm such a relationship. In one study, incompetence of the great or small saphenous veins had a greater impact on QOL than nonsaphenous varicosities.7 Another study revealed either a weak correlation or no correlation between the diameter of the incompetent great saphenous vein and impaired QOL in patients with varicose veins.23 Similarly, there was no association between venous symptoms and systemic inflammatory markers, such as the von Willebrand factor, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 [ICAM- 1], vascular cell adhesion protein 1 [VCAM-1], E-selectin, P-selectin, L-selectin, vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], interleukin 1α (IL-1α), IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α(TNF-α).14

Interventions

Some studies examined the impact of interventions aimed at reducing venous incompetence (compression therapy or ablation of varicose veins) on venous symptoms and QOL. It might be assumed that if the symptoms were produced by venous disease, then such treatments should result in fewer complaints and a better QOL. However, only some of the patients studied were free of symptoms after an otherwise successful treatment of their varicose veins.24-26 On the other hand, a recurrence of venous incompetence was not always accompanied by a return of the symptoms.27,28

As expected, wearing compression stockings resulted in improved QOL, not only in advanced (C3 to C5) venous patients, but also in those with early (C2) disease.19 A similar improvement in QOL was demonstrated by another study in patients with incompetent great saphenous veins (clinically C2 to C4). The authors of this study revealed that improvement in QOL was mainly due to the relief of venous symptoms. In this study, an invasive treatment (radiofrequency ablation of the great saphenous vein together with phlebectomies of superficial varicosities) resulted in an even greater improvement in QOL. An important finding of this study was that relief of symptoms by compression therapy was a good predictor of successful surgical treatment. Patients who improved their symptoms with compression therapy were more likely to experience further clinical improvement after ablation of varicose veins. However, a substantial proportion of patients who did not improve their QOL after compression therapy benefited from surgical treatment of varicose veins. Thus, not all clinical symptoms of CVD could be relieved by compression alone.29

In an interventional study, QOL significantly improved (71% of the patients got better) after surgical excision of varicose veins. Patients with uncomplicated (C2 to C3) and complicated (C4 to C6) venous disease experienced a similar improvement in their QOL. In this study, the patients with a poorer QOL before surgery were more likely to benefit from the treatment.30 Similarly, in an observational study on patients receiving ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy of symptomatic incompetent great or small saphenous veins (patients with asymptomatic varicosities were not included), there was a significant improvement in QOL after treatment. This improvement was seen in both C2 to C3 and C4 to C5 patients. Improvement in QOL was similar in patients with great and small saphenous vein varicosities. Also, considering the mental domains of the QOL questionnaire, there was no difference in terms of QOL according to whether uncomplicated (C2 to C3) or complicated (C4 to C5) varicose veins were treated. A similar improvement in QOL was observed in patients with symptomatic varicose veins in the great or small saphenous vein territories, who underwent ablation of incompetent veins, and were randomized for surgical stripping and phlebectomies, endovenous laser treatment, or foam sclerotherapy. This improvement in QOL was similar, irrespective of the method used to treat varicosities.31 A comparable improvement in QOL was also seen in the studies that assessed patients with varicose veins after ultrasound-guided foam sclerotheraphy32 or endovenous laser ablation.33 On the contrary, physical aspects of QOL were significantly worse in patients with C4 to C5 venous disease. Interestingly, regarding physical domains of QOL, the patients with uncomplicated varicosities benefited more from the treatment in comparison with those with complicated varicose veins.6

Other influencing factors

It seems that CVD is not a uniform clinical entity in terms of clinical symptoms and impaired QOL. Thrombotic events, bilateral varicosities, and recurrence of varicose veins significantly affect the natural history of the disease. In the VEINES study, a multivariable regression analysis revealed that a previous venous thromboembolism was a predictor of poorer QOL, independent of variables, such as age, sex, country of residence, education, BMI, duration of CVD, and the presence of comorbidities.34 In this study, an analysis that adjusted for the CEAP clinical class, confirmed that a previous thromboembolism was an independent predictor of a decreased QOL.<34,35 Bilateral varicose veins were associated with worse QOL than unilateral venous incompetence,7 while some studies showed that QOL was significantly reduced in patients with recurrent varicosities compared with patients with primary varicose veins.6,36 In one study, QOL impairment was no worse in recurrent varicosities than primary varicosities.7

Conclusion

Considering the inconsistent results in the above-presented studies, a reasonable explanation of the enigma of venous symptoms is not easy to discern. Certainly, in many of these studies, a selection bias occurred, either skewing the cohorts studied toward the patients presenting with real symptomatic CVD (clinical symptoms actually caused by venous disease) or toward the patients suffering from alternative sources of complaints, primarily osteoarticular pathologies. The first scenario was more likely if the patients qualifying for surgical treatment of varicose veins were evaluated, since they were initially screened by an experienced clinician and those with nonvenous complaints were not very likely to enter such a study. The second scenario could occur in the surveys that used advertising in mass media to select participants, thus mostly attracting people with pain or other leg symptoms primarily associated with neurological and orthopedic problems, and not with venous incompetence. Some researchers speculated that differences between the studies in terms of association of venous symptoms with CVD could result from different expressions of such complaints in particular languages, making a comparison of the studies conducted in different countries difficult.8

Nonetheless, venous symptoms seem to be nonspecific for CVD and can be reported by patients presenting with other diseases. Many uncomplicated varicose veins can be asymptomatic or cause very few symptoms.3,6-10 In some patients with varicose veins, the symptoms and impaired QOL may result from concomitant components of venous disease, such as inflammatory skin changes, and may not directly cause dilated veins. In many of these patients, clinical symptoms are not permanent, but can be seen at the end of the day (when clinical trials are not routinely performed) or only during hot periods of the year (again, not a typical season to perform studies). Moreover, the research is telling us that a large proportion of venous symptoms have their sources in coexisting nonvenous pathologies.2,11,15 This is of particular importance in C1 and C2 patients, since those with more severe forms of venous incompetence usually experience symptoms caused by venous disease. The majority of symptoms in the patients with telangiectasias and uncomplicated varicose veins do not seem to be of venous origin. Rather, especially if such symptoms are severe, an alternative cause should be considered.37

Unfortunately, available QOL questionnaires do not include questions that facilitate recognition of the real cause of symptoms. In addition, a thorough medical history and clinical examination, together with a vascular sonographic assessment, were not used by most of the studies that evaluated an association of venous symptoms with the presence of venous disease. Instead, rather nonspecific QOL questionnaires and simple clinical tests were utilized.

Studies with better designs, such as the recent Dutch2 or German16 ones, may put an end to the controversy over this problem. For the time being, from a practical point of view, it is important to distinguish patients with actual symptomatic varicosities from those patients with other sources of pain and other “venous” complaints. If such patients are not properly diagnosed initially, it is inevitable that some of them will be dissatisfied by the treatment for varicose veins, since the real cause of their complaints (eg, hip arthrosis) will not be addressed by a vascular procedure. Currently, we lack solid information on the prevalence of the pathologies that cause such “venous” symptoms in the population of patients with CVD. Still, the most common pathologies that may be responsible and should be considered in clinical practice include spinal disc herniation, hip and knee arthrosis, peripheral arterial disease, joint and ligament overload due to obesity, and peripheral neuropathy. These nonvenous problems can be quite prevalent in patients with CVD, especially those presenting with severe disease. For example, in one study, researchers have found that the majority of C5 to C6 patients presented with reduced ankle mobility and symptoms of peripheral neuropathy.38 There are also many patients who suffer from leg pain and edema after the use of different medications, especially calcium channel blockers.39 In the case of such adverse drug-related events occurring in patients with varicose veins, an invasive or pharmacological treatment for venous incompetence will not relieve symptoms. Instead, the medication should be discontinued. Similarly, in patients complaining of symptoms caused by osteoarticular, neurological, or arterial pathologies, the disease that is the source of the complaints should primarily be addressed.

1. Lindsey B, Campbell WB. Rationing of treatment for varicose veins and use of new treatment methods: a survey of practice in the United Kingdom. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;12:19-20.

2. Van der Velden SK, Shadid NH, Nelemans PJ, Sommer A. How specific are venous symptoms for diagnosis of chronic venous disease? Phlebology. 2014;29:580-586.

3. Carpentier PH, Cornu-Thénard A, Uhl JF, Partsch H, Antignani PL; Société Française de Médecine Vasculaire; European Working Group on the Clinical Characterization of Venous Disorders. Appraisal of the information content of the C classes of CEAP clinical classification of chronic venous disorders: a multicenter evaluation of 872 patients. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:827-833.

4. Andreozzi GM, Cordova RM, Martini R, D’Eri A, Andreozzi F; Quality of Life Working Group on Vascular Medicine of SIAPAV. Quality of life in chronic venous insufficiency: an Italian pilot study of the Triveneto Region. Int Angiol. 2005;24:272-277.

5. Kaplan RM, Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Bergan J, Fronek A. Quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: San Diego population study. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:1047-1053.

6. Darvall KA, Sam RC, Bate GR, Silverman SH, Adam DJ, Bradbury AW. Changes in health-related quality of life after ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy for great and small saphenous varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:913-920.

7. Staniszewska A, Tambyraja A, Afolabi E, Bachoo P, Brittenden J. The Aberdeen varicose vein questionnaire, patient factors and referral for treatment. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;46:715-718.

8. Carpentier PH, Maricq HR, Biro C, Ponçot-Makinen CO, Franco A. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical patterns of chronic venous disorders of lower limbs: a population-based study in France. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:650-659.

9. Kurz X, Lamping DL, Kahn SR, et al; VEINES Study Group. Do varicose veins affect quality of life? Results of an international population-based study. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:641-648.

10. Chiesa R, Marone EM, Limoni C, Volontè M, Petrini O. Chronic venous disorders: correlation between visible signs, symptoms, and presence of functional disease. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:322-330.

11. Bradbury A, Evans C, Allan P, Lee A, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FG. What are the symptoms of varicose veins? Edinburgh vein study cross sectional population survey. BMJ. 1999;318:353-356.

12. Bradbury A, Evans C, Allan P, Lee A, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FG. The relationship between lower limb symptoms and superficial and deep venous reflux on duplex ultrasonography: the Edinburgh Vein Study. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:921- 931.

13. Duque MI, Yosipovitch G, Chan YH, Smith R, Levy P. Itch, pain, and burning sensation are common symptoms in mild to moderate chronic venous insufficiency with an impact on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:504-508.

14. Howlader MH, Smith PD. Symptoms of chronic venous disease and association with inflammatory markers. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:950-954.

15. Langer RD, Ho E, Denenberg JO, Fronek A, Allison M, Criqui MH. Relationships between symptoms and venous disease: the San Diego population study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1420-1424.

16. Wrona M, Jöckel KH, Pannier F, Bock E, Hoffmann B, Rabe E. Association of venous disorders with leg symptoms: results from the Bonn Vein Study 1. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50:360-367.

17. Ruckley CV, Evans CJ, Allan PL, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG. Telangectasia in the Edinburgh Vein Study: epidemiology and association with trunk varices and symptoms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:719-724.

18. Kröger K, Ose C, Rudofsky G, Roesener J, Hirche H. Symptoms in individuals with small cutaneous veins. Vasc Med. 2002;7:13-17.

19. Andreozzi GM, Cordova R, Scomparin MA, Martini R, D’Eri A, Andreozzi F; Quality of Life Working Group on Vascular Medicine of SIAPAV. Effects of elastic stocking on quality of life of patients with chronic venous insufficiency: an Italian pilot study on Triveneto Region. Int Angiol. 2005;24:325-329.

20. Dunić I, Medicinal L, Bobić B, Djurković- Djaković O. Patients’ reported quality of life in chronic venous disease in an outpatient service in Belgrade, Serbia. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:616-620.

21. Darvall KA, Bate GR, Adam DJ, Bradbury AW. Generic health-related quality of life is significantly worse in varicose vein patients with lower limb symptoms independent of CEAP clinical grade. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44:341-344.

22. Moura RM, Gonçalves GS, Navarro TP, Britto RR, Dias RC. Relationship between quality of life and the CEAP clinical classification in chronic venous disease. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2010;14:99-105.

23. Gibson K, Meissner M, Wright D. Great saphenous vein diameter does not correlate with worsening quality of life scores in patients with great saphenous vein incompetence. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:1634-1641.

24. Baker DM, Turnbull NB, Pearson JC, Makin GS. How successful is varicose vein surgery? A patient outcome study following varicose vein surgery using the SF-36 health assessment questionnaire. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1995;9:299- 304.

25. Hamel-Desnos CM, Guias BJ, Desnos PR, Mesgard A. Foam sclerotherapy of the saphenous veins: randomized controlled trial with or without compression. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:500-507.

26. Shadid N, Ceulen R, Nelemans P, et al. Randomized clinical trial of ultrasoundguided foam sclerotherapy versus surgery for the incompetent great saphenous vein. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1062-1070.

27. Saarinen J, Suominen V, Heikkinen M, et al. The profile of leg symptoms, clinical disability and reflux in legs with previously operated varicose disease. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:51-55.

28. Merchant RF, Pichot O; Closure Study Group. Long-term outcomes of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration of saphenous reflux as a treatment for superficial venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:502-509.

29. Lurie F, Kistner RL. Trends in patient reported outcomes of conservative and surgical treatment of primary chronic venous disease contradict current practices. Ann Surg. 2011;254:363-367.

30. Eskelinen E, Räsänen P, Albäck A, et al. Effectiveness of superficial venous surgery in terms of quality-adjusted years and costs. Scand J Surg. 2009;98:229-233.

31. Brittenden J, Cotton SC, Elders A, et al. A randomized trial comparing treatments for varicose veins. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1218-1227.

32. Darvall KA, Bate GR, Bradbury AW. Patient-reported outcomes 5-8 years after ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy for varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1098- 1104.

33. El-Sheikha J, Nandhra S, Carradice D, et al. Clinical outcomes and quality of life 5 years after a randomized trial of concomitant or sequential phlebectomy following endovenous laser ablation for varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1093- 1097.

34. Kahn SR, M’Lan CE, Lamping DL, et al. Relationship between clinical classification of chronic venous disease and patient-reported quality of life: results from an international cohort study. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:823-828.

35. Kahn SR, M’Lan CE, Lamping DL, Kurz X, Bérard A, Abenhaim L; Veines Study Group. The influence of venous thromboembolism on quality of life and severity of chronic venous disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:2146-2151.

36. Beresford T, Smith JJ, Brown L, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. A comparison of health-related quality of life of patients with primary and recurrent varicose veins. Phlebology. 2003;18:35- 37.

37. Yetkin E. Complexity of venous symptoms. Phlebology. 2015 Feb 19. Epub ahead of print.

38. Yim E, Vivas A, Maderal A, Kirsner RS. Neuropathy and ankle mobility abnormalities in patients with chronic venous disease. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:385-389.

39. Sica D. Calcium channel blocker-related peripheral edema: can it be resolved? J Clin Hypertension (Greenwich). 2003;5:291-295.

40. Simka M. Symptoms and signs of chronic venous disorders: can we put an end to the controversy? Medicographia. 2015;37:2-25.