Changes in the diameter and valve closure time of leg veins across the menstrual cycle

2014;33:803-809.

This article presents an evaluation of a specific cohort of young, nulliparous women with duplex ultrasound of the lower extremities at various stages of the menstrual cycle. The study was comprised of an evaluation of 106 limbs in 53 women with homogeneity in their demographic makeup. They lacked, for the most part, any of the classic risk factors for the development of chronic venous deficiency and were all classified as class 0 (no venous disease) on the 7-point clinical, etiologic, anatomic and pathophysiologic (CEAP) scale.

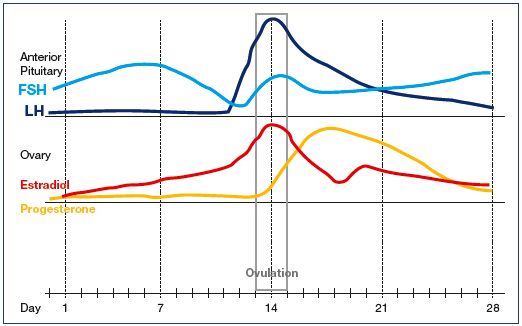

The study showed that the differences in vein diameter and valve closure times (using B-mode and color-flow imaging, as well as pulsed Doppler spectral analysis of the deep and superficial venous systems) were statistically significant across the different stages of the menstrual cycle. The authors correctly point out that estrogen levels peak at mid-cycle ovulation and decrease slightly during the second half of the menstrual cycle. Progesterone levels, however, remain low until mid-cycle ovulation, peak in the mid-secretory (luteal) phase, and drop precipitously prior to the onset of menstrual flow (Figure 1). In fact, this phenomenon is so well known in the gynecological community that the onset of menses is synonymous with “progesterone withdrawal.”

Figure 1. Approximate concentrations of pituitary and ovarian hormones during the

menstrual cycle.

Abbreviations: FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.

The sex hormone progesterone, a smooth muscle relaxant, plays a vital role during gestation by allowing the smooth muscle of the gravid uterus to grow to accommodate the enlarging and developing fetus. One could argue, as the late Professor John Bergan often did in conversations with me, that progesterone is potentially “poison” for the venous system. I’ve been of the opinion that stimulation of progesterone receptors of the vein wall in the later part of the menstrual cycle contributes to some of the leg discomfort associated with the premenses period–a so-called “luteal phase vasodilation syndrome.”1 Along with other somatic complaints and cognitive symptoms, these characteristics are well established in the gynecological literature and are often collectively referred to as the “premenstrual syndrome (PMS).”2 This study is another step in objectively identifying some of the physiological changes associated with the luteal phase. However, the study did not describe any associated symptoms in the participants.

The authors discuss how an ideal study would include following these participants over 10 to 20 years. As discussed, a study design of this type may well be impractical. For example, two identical twin sisters may share the same genetic risk profile for the development of venous disease. However, one twin may have several pregnancies and children, use oral contraceptives, and engage in an occupation requiring prolonged sitting or standing, while the other twin may be nulliparous, use barrier contraceptives, and work in a profession not requiring prolonged sitting or standing.

More studies of this nature are required to determine how the physiological changes associated with the menstrual cycle can contribute to the physical complaints associated with the luteal phase, as well as the development of the full spectrum of venous disease. Contemporary phlebology practice requires a collaborative approach to such studies, drawing on the expertise of phlebologists, interventional radiologists, gynecologists, and others who care for female patients.

REFERENCES

2. G reene R, Dalton K. The premenstrual syndrome. Br Med J. 1953;1:1007-1014.

1. Ninia JG. Premenstrual symptoms in lower limbs and Duplex scan investigations. Phlebolymphology. 2008;15:125-128.