Presence of varices after operative treatment: a review

Part 1: This is the first of 2 chapters that will comprise the ‘PREsence of Varices After operatIve Treatment (PREVAIT)’. These 2 chapters will be published in the journal consecutively.

Abstract

Background: PREsence of Varices after operatIve Treatment (PREVAIT ) occurs in 13% to 65% of patients and remains a debilitating and costly problem. The first part of this review provides an overview of the current understanding of the etiology and pathogenesis of PREVAIT . Methods: A PubMed search was conducted in English and French for the years 2000-2013 by using keywords (Duplex scanning, endothermal ablation, neovaricoses, REVA S, sclerotherapy, varices recurrence, varicose vein, varicose vein surgery).

Results: Epidemiology and socioeconomic consequences were analyzed according to the initial operative treatment. Then a classification of possible mechanisms and causes for PREVAIT are classified in terms of tactical and technical errors, evolution of the disease, considering that the systematic use of ultrasound investigation has minimized the former.

Conclusion: The cause and underlying mechanisms for recurrences of varicose veins are poorly understood. Large prospective studies should be performed to clear up the picture.

Background

The presence of varicose veins after operative treatment is a common, complex, and costly problem for both the patients and the physicians who cope with venous diseases. An international consensus meeting was held in Paris in 1998 and guidelines were proposed for the definition and description of REcurrent Varices After Surgery (REVA S).1 In a related article from 2000, 94 references dealing with recurrence after operative treatment or including information on its presence or absence after operative treatment were listed. Since then, 140 additional publications in English and French have been identified.2-141

Classical surgery, which used to be the most frequent operative procedure for treating varicose veins in the last decade, has been progressively taken over by chemical and thermal ablation procedures, and to a slight extent, by mini-invasive surgeries including CHIVA (French acronym for ambulatory conservative hemodynamic management of varicose veins)142 and ASVAL (French acronym for tributary varices phlebectomy under local anesthesia).143,144 Therefore, the experts of the VEIN-TERM transatlantic interdisciplinary consensus meeting suggested replacing the classical surgery-related acronym REVA S with PREVAIT (PREsence of Varices After Interventional Treatment).145

During the same meeting, the following terms were defined:

1. Recurrent varices: Reappearance of varicose veins in an area previously treated successfully.

2. Residual varices: Varicose veins remaining after treatment.

3. PREVAIT : PREsence of Varices (residual or recurrent) After Interventional Treatment.

The concept of PREVAIT was developed for two reasons: (i) it is often difficult to correctly classify the results of initial procedures done by others and consequently to differentiate recurrent varices from residual varices; and (ii) the term REVA S was limited to patients previously treated by surgery as previously mentioned. The term PREVAIT encompasses both recurrent and residual varicose veins after any kind of operative treatment including open surgery and endovenous procedures, either thermal or chemical.

Table I. REVAS Classification sheet.

Modified after reference 98: Perrin et al. Eur J Vasc Endovasc

Surg. 2006;32:326-333.

It was also argued that the term ‘interventional treatment’ was not equivalent to the term ‘operative treatment,’ ecause even noninvasive therapies such as venoactive drugs or compression therapy may modify the natural history of varicose veins and be considered as ‘interventional.’

In 2000, a REVA S classification form was elaborated for future studies (Table I). The REVA S classification was hen subject to intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility,98 and then used in an international survey.95,97 A form similar to this should be adapted to PREVAIT for possible future studies.

AIM

The purpose of this review is to analyze all available data on PREVAIT in order to help physicians identify the best operative treatment, if any, likely to prevent PREVAIT . Such analysis might help build a revised classification, as mentioned above.

Material and methods

A PubMed search was conducted to retrieve published articles in English and French for the years 2000-2013 using the keywords varices recurrence, REVA S, endothermal ablation, sclerotherapy, varicose vein surgery, varicose vein, duplex scanning, neovaricose, and their counterparts in French. Abstracts were not selected, only publications dealing with PREVAIT were chosen, some of them focused on PREVAIT patients, others concerned patients presenting with varices and operatively treated whose follow-up specified the absence or presence of varices.

Results

Since the REVA S publication,1 140 articles on recurrent varices have been published.2-141 29 randomized trials were added to the references from the REVA S articles list, taking the total papers regarding randomized trials to 34.6,7,13,16,17,42,52,61,62,66,69,80,83,90,92,103,107-111,117,118,120,122,124,136,137,140,146-152 Epidemiologic data and socioeconomic consequences will be analyzed according to the initial procedures, which will be followed by a discussion of the possible mechanisms for PREVAIT occurrence.

Magnitude of REVAS occurrence

With open surgery

The most documented outcomes are provided by classical surgery, but most studies are retrospective. In a 34-year follow-up study, varicose veins were present in 77% of the lower limbs examined and were mostly symptomatic: 58% were painful, 83% had a tired feeling, and 93% showed a reappearance of edema.50

Two prospective studies concerning classical surgery are available with a follow-up of 5 years.72,133 In both studies, patients were preoperatively investigated with duplex scanning (DS) and treated by high ligation, saphenous trunk stripping, and stab avulsion. In the Kostas et al series, 28 out of 100 patients had PREVAIT after 5 years: recurrent varices mainly resulting from neovascularization in eight limbs (8/28, 29%), new varicose veins as a consequence of disease progression in seven limbs (7/28, 25%), residual veins due to tactical errors (eg, failure to strip the great saphenous vein) in three limbs (3/28, 11%), and complex patterns in ten limbs (10/28, 36%).72 In the Van Rij et al series, 127 limbs (CEAP class C2–C6) were evaluated postoperatively by clinical examination, DS, and air plethysmography (APG). At the clinical evaluation, recurrence of varicose veins was progressive from 3 months (13.7%) to 5 years (51.7%). In line with clinical changes, a progressive deterioration in venous function was measured by APG and a recurrence of reflux was assessed by DS.133

These 2 studies showed that recurrence of varicose veins after surgery is common, even in highly skilled centers, and even if the clinical condition of most affected limbs after surgery improved compared with ‘before surgery.’ Progression of the disease and neovascularization are responsible for more than half of the recurrences. Rigorous evaluation of patients and assiduous surgical techniques might reduce the recurrence resulting from technical and tactical failures.

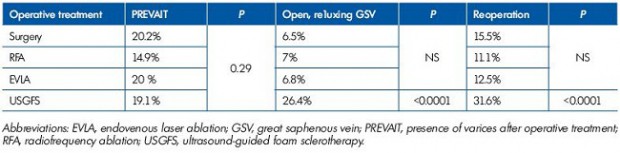

Table II. Rasmussen 3-year clinical and DS outcome and reoperation percentages.

Modified after reference 111: Rassmusen et al. J Vasc Surg: Venous and Lym Dis. 2013;1:349-356.

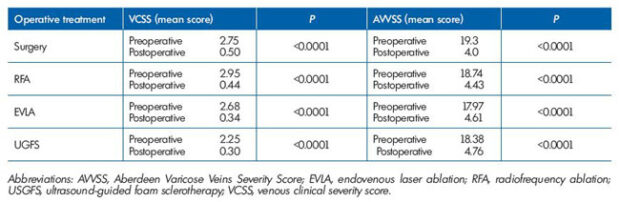

Table III. Pre and postoperative VCSS and AVVSS according to operative treatment.

Modified after reference 111: Rassmusen et al. J Vasc Surg: Venous and Lym Dis. 2013;1:349-356.

In a four arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) by Rassmussen et al, endovenous laser ablation (EVLA ), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS), and surgical stripping for great saphenous varicose veins (GSV ) were compared with a 3-year follow-up, the rate of PREVAIT was reported in each arm (Table II).111 There was no significant difference between the 4 procedures (P=0.29) in terms of clinical recurrence, but the presence of persisting reflux in the GSV was significantly higher in UGFS compared with the other 3 methods (P<0.0001) as well as the reoperation rate (P<0.0001).

Regardless of the procedure used, the severity of varicose disease as assessed with the Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS) was significantly reduced, and the quality of life using the Aberdeen Varicose Veins Severity Score (AVV SS) was significantly improved after all operative treatments no matter which procedure was used (P<0.0001; Table III)

With radiofrequency ablation

From a multicenter prospective study, recurrence rates after RFA with ClosurePlus® were reported. At the 5-year follow-up, PREVAIT was estimated at 27.4%.84 A 3-year follow-up RCT comparing ClosureFast®-RFA of the GSV with or without treatment of calf varicosities did not document the PREVAIT rate, but only the obliteration rate on DS investigation, venous clinical severity score (VCSS), and the presence of symptoms.102 In the four arm study by Rassmussen et al,111 there was no statistical difference regarding PREVAIT rates between RFA and the other operative procedures (P=0.29; Table II).

With endovenous laser ablation

At the 2-year follow-up, a RCT by Rass et al found no significant difference (P=0.15) when comparing EVLA with classical surgery (EVLA 16.2% vs 23.1%).107 An Italian group reported a PREVAIT rate of 6% at month 36.2 In a RCT comparing EVLA with GSV stripping with a 5-year follow-up, PREVAIT was reported in 36% and 37% of patients, respectively, with no statistical difference between groups (P=0.9). In this study, reoperative treatment was performed in 38.6% and 37.7%, respectively, mainly by UGFS.110 Again in the four arm study by Rassmussen et al,111 there was no statistical difference regarding PREVAIT rates between EVLA and the other operative procedures (P=0.29; Table II).

Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy

Hamel-Desnos et al reported a 36% and 37% recanalization rate at the 2-year follow-up with UGFS, one injection with 1% and 3% polidocanol foam, espectively.62 In a RCT of UGFS vs surgery for the incompetent GSV with a follow-up of 2 years, PREVAIT was identified in 9% vs 11.3%, respectively. P=0.407, which is not significant. Conversely, reflux was significantly higher in UGFS (P=0.003).118

In the British long-term RCT by Kalodiki et al of UGFS combined with sapheno-femoral ligation vs standard surgery for GSV, clinical severity of venous disease assessed by VCSS and venous segmental disease score (VSDS) were equally reduced in both groups, and the quality of life equally improved as well (using AVV Q and 36-Item Short-Form).69 Unfortunately, PREVAIT was not reported in this study.

With procedures saving the saphenous trunk

CHIVA

PREVAIT was assessed when using the CHIVA method vs classical surgery in 2 RCT’s with a follow-up of 5 and 10 years.16,90 In both studies, the Hobbs classification was used to assess PREVAIT.148,149

If we add failure (presence of VV >0.5 cm) and slightly improved patients in terms of cosmetic appearance (presence of VV <0.5 cm), the outcomes were as follows: (i) At 5 years postsurgery, the PREVAIT rate in the group operated by stripping was 70.7% vs 55.6% in the CHIVA group (P>0.001).90 In the 10-year follow-up RCT by Carandina, the recurrence rate of varicose veins was significantly higher in the stripping group compared with the CHIVA group (CHIVA , 18%; stripping, 35%; P<0.04 Fisher’s exact test). The associated risk of recurrence at 10 years was doubled in the stripping group (odds ration [OR], 2.2; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1-5; P=0.04).16 In both RCTs, the recurrence rate was lower with CHIVA ,90,16 yet there is a great discrepancy between the studies, PREVAIT was unexpectedly higher in the 5-year follow-up RCT,90 compared with the 10-year follow-up.16

ASVAL

No published data is available regarding the mid-term results.

Socioeconomic consequences

No socioeconomic data on PREVAIT has been published. When a redo surgery is performed, the cost is higher than the first surgery because of the number of peri- and postoperative complications. In one observational study, 40% of patients had complications after classical surgery for PREVAIT.64

Possible mechanisms leading to PREVAIT

They must be classified in 2 groups: tactical errors and technical problems.

Tactical errors

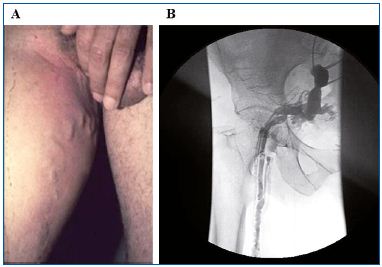

Tactical errors are common to all operative treatments. It includes wrong or incomplete diagnosis of the extent and/or location of varices, source of reflux, onidentification of deep venous anomalies including pelvic reflux (Figures 1, Figure 2), primary vein compression or reflux, and posthrombotic syndrome. Fortunately, the systematic use of DS before any operative treatment has minimized this cause of error. In most of the articles published before systematic use of preoperative DS, tactical error was the most frequent mechanism leading to PREVAIT .

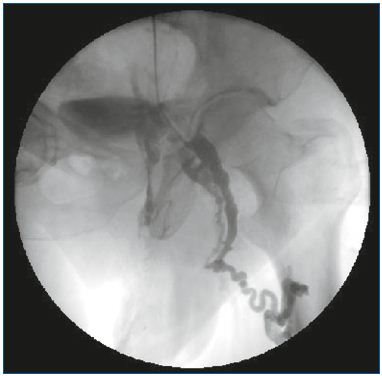

Figure1. PREVAIT clinical aspect.

A. Pelvic vein leak. B. Selective pelvic venography from the same

patient as A. (Courtesy of Drs Monedero and Zubicoa).

Figure 2. Selective pelvic venography.

After a Valsalva maneuver. Reflux through the obturator vein

feeding the nonsaphenous vein network.

(Courtesy of Drs Monedero and Zubicoa).

There is a consensus on the fact that saphenous ablation provides a better outcome when saphenous trunk incompetence is present and when classical surgery, thermal or chemical, is performed. Yet, the proponents of the CHIVA and ASVAL procedures contest this point by arguing that trunk conservation would provide good results. In the CHIVA procedure, the argument is that the preservation of the saphenous trunks together with sparing of their functions (cutaneous and subcutaneous drainage) is allowed thanks to appropriate shunt disconnections that breaks the higher-than-normal hydrostatic pressure and subsequently improves hemodynamics.16,90,142 In the ASVAL method, the ablation of the reservoir incompetent tributaries leads to a reduction in the reflux in the saphenous trunk.143,144

Technical problems related to the first operative treatment (surgery, thermal, or chemical ablation)

Such problems can overlap in the same patient, and some are specific and related to the procedure used, while others are identified no matter what procedure was used.

Surgery

The most frequent technical error quoted in classical surgery was non flush ligation at the saphenofemoral junction (SFJ; Figure 3) or at the saphenopopliteal junction (SPJ; Figure 4). This point is now controversial as some series with conservation of the SFJ claim to achieve excellent results including patients with incompetent terminal valve.152 Several authors continue to state that non flush ligation of the saphenous termination is responsible for frequent recurrence,41,52 particularly over the long-term.55-57 In the CHIVA technique, PREVAIT would be mainly related to wrong preoperative marking and inappropriate technique.90

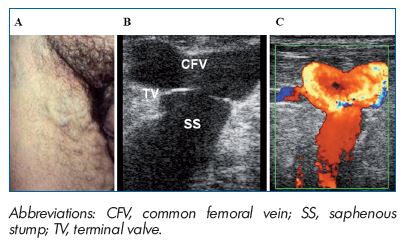

Figure 3. PREVAIT clinical aspect.

A. Massive groin recurrence related to non flush high ligation

in a patient with an incompetent GSV terminal valve. B. Same

patient with a B mode ultrasound. The terminal valve is identified

at the saphenofemoral junction. (Courtesy of Dr Gillet). C. Same

patient with a color duplex ultrasound. Massive reflux induced

by a Valsalva maneuver. (Courtesy of Dr Gillet).

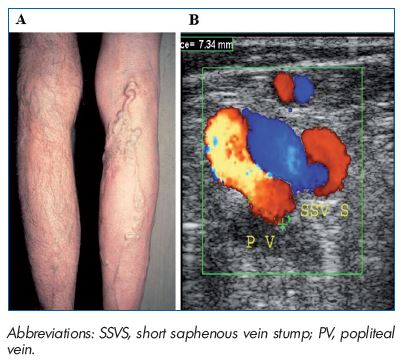

Figure 4. PREVAIT clinical aspect.

A. Popliteal fossa massive recurrence related to non-flush

high ligation in a patient with an incompetent SSV terminal

valve. B. Postoperative duplex scanning identified reflux in the

SSVS, which feeds the varicose network after the compressiondecompression

maneuver. (Courtesy of Dr Gillet).

Thermal ablation

Inadequate technique consisting mainly of delivering insufficient energy, irradiance, or fluence in laser or radiofrequency procedures should be responsible for short or long-term recanalization of the treated vein.

Chemical ablation

Inadequate technique as well as inappropriate sclerosing agent dose should be responsible for short or long-term recanalization of the treated vein.

Technical problems not related to initial treatment

The neovascularization phenomenon was discovered 25 years ago, but remains not fully elucidated.152 It occurs mainly at the SFJ (Figure 5) and less frequently at the SPJ (Figures 6), and is considered, in many articles, as the main cause of PREVAIT after correct classical surgery.28,29,134,153,154 El Wajeh et al contests the term neovascularization and favors adaptive dilatation of preexisting venous channels (vascular remodeling), probably in response to abnormal hemodynamic forces.43 According to Lemasle et al, this phenomenon is related to preexisting anatomical anomalies.79 Egan et al minimizes its frequency as well as its importance in groin recurrence. 41 However, neovascularization has been reported not only in procedures including SFJ or SPJ ligation, but also after thermal ablation,76 albeit at a lower frequency.71,124

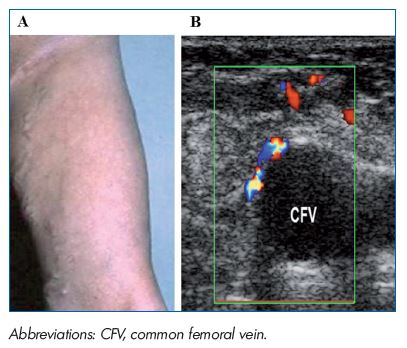

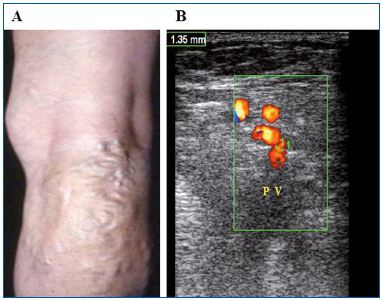

Figure 5. PREVAIT clinical aspect.

A. A varicose network at the thigh just below a previous groin

incision related to neovascularization. B. Same patient with a

duplex scan. Small refluxive veins identified above the CFV after

a Valsalva maneuver. (Courtesy of Dr Gillet).

Figure 6. PREVAIT clinical aspect.

A. A varicose network at the popliteal related to neovascularization.

B. Same patient with a duplex scan. Varicose network

above a refluxive popliteal vein (Courtesy of Dr Gillet).

Evolution of the disease

It should never be forgotten that superficial venous disease is a chronic condition that tends to progress over time.104 In other words, previously unaffected superficial veins or perforators may become incompetent. Varices may develop in the same territory initially treated including saphenous tributaries that were not incompetent at the time of the operative treatment or in another superficial vein territory.

Risks factors for chronic venous disease progression and, in particular, varices have been investigated in many prospective studies.155 However, underpinnings and constitution risk factors for disease progression are still poorly understood. It is generally accepted that there is a strong family predisposition, not only for presenting varicose veins, but also for developing recurrence related to disease evolution. The precise nature of the genetic basis for this family predisposition is far from clear. To shed more light on this issue, it will not be sufficient to study single genes, potentially implicated in varices. Instead, genome wide association studies will be needed using very large sample sizes to further unravel the genetic basis of varices and chronic venous insufficiency.156

1. Perrin M, Guex JJ, Ruckley CV, et al. Recurrent varices after surgery (REVA S), a consensus document. Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;8:233-245.

2. Agus B, Mancini S, Magi G. The first 1000 cases of Italian Endovenous-Laser Working Group (IEWG): Rational, and long terms outcomes for the 1999-2003 period. Int Angiology. 2006;25:209-215.

3. Ali SM, Callam MJ. Results and signifiance of colour duplex assessment on the deep venous system in recurrent Varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:97-101.

4. Allaf N, Welch M. Recurrent varicose veins: inadequate surgery remains a problem. Phlebology. 2005;20:138-114.

5. Allegra C, Antignani PL, Carlizza A. Reccurent varicose veins following surgical treatment: our experience with five years follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:751-756.

6. Belcaro G, Nicolaides AN, Cesarone NM, et al. Flush ligation of the saphenofemoral junction vs simple distal ligation A randomised, 10-year, follow-up. The safe study. Angéiologie. 2002;54:19-23.

7. Belcaro G, Cesarone NM, Di Renzo A, et al. Foam sclerotherapy, surgery, sclerotherapy and combined treatment for varicose veins A 10-year, prospective, randomised, controlled trial (VEDICO trial ). Angiology. 2003;54:307-315.

8. Bhatti TS, Whitman B, Harradine K, et al. Causes of re-recurrence after polytetrafluoroethylene patch saphenoplasty for recurrent varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1356-1360.

9. Beresford T, Smith JJ, Brown L, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AHA. Comparison of health-related quality of life of patients with primary and recurrent varicose veins. Phlebology. 2003;18:35- 37.

10. Blomgren L, Johansson G, Dahlberg- Akerman A, et al. Recurrent varicose veins: Incidence, risk factors and groin anatomy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27:269-274.

11. Blomgren L, Johansson G, Dahlberg- Akerman, et al. Changes in superficial and perforating vein reflux after varicose vein surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:315- 320.

12. Brake M. Pathogenesis and etiology of recurrent varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:860-868.

13. Bountourouglou DG, Azzam M, Pathmarajh M, et al. Ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy combined with sapheno-femoral ligation compared to surgical treatment of varicose veins: early results of a randomised contolled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:93- 100.

14. Bridget M, Donnelly M, Tierney S. Recurrent varicose veins after surgery. Br J Surg. 2006;38:49.

15. Cardia G, Catalano G, Rosafio I, Granatiero M, De Fazio M. Recurrent varicose veins of the legs. Analysis of a social problem. G Chir. 2012;33:450- 454.

16. Carandina S, Mari C, De Palma M, et al. Varicose vein stripping vs haemodynamic correction (CHIVA ): a long term randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:230-237.

17. Carradice D, Mekako AI, Mazari FA, Samuel N, Hatfield J, Chetter IC. Randomized clinical trial of endovenous laser ablation compared with conventional surgery for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2011:98:501- 510.

18. Castenmiller PH, de Leur K, de Jong TE, van der Laan L. Clinical results after coil embolization of the ovarian vein in patients with primary and recurrent lower-limb varices with respect to vulval varices. Phlebology. 2013;28:234-238.

19. Chong CS, Toh BC, Chiang V, Cheng SC, Lee CW. Pattern of recurrence of lower limb varicose veins post EVLT : a single center experience. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37:S159.

20. Smith PC. Chronic venous disease treated by ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32:577- 583.

21. Creton D. Surgery of great saphenous vein recurrences: the presence of diffuse varicose veins without a draining residual saphenous trunk is a factor of poor prognosis for long-term results. J Phlebolymphology. 2002;2:83-89.

22. Creton D. Surgery for recurrent saphenofemoral incompetence using expanded polytetrafluoroethylene patch interposition in front of the femoral vein: long-term outcome in 119 extremities. Phlebology. 2002;16:93-97.

23. Creton D. 125 réinterventions pour récidives variqueuses poplitées après exérèse de la petite saphène. Hypothèses anatomiques et physiologiques du mécanisme de la récidive. J Mal Vasc. 1999;24:30-36.

24. Creton D, Uhl JF. Foam Sclerotherapy Combined with Surgical Treatment for Recurrent Varicose Veins: Short Term Results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33:619-624.

25. Creton D. A non draining saphenous system is a factor of poor prognosis for long-term results in surgery of great saphenous vein recurrences. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:744-749.

26. Darke SG, Baker SJ. Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy for the treatment of varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2006;93:969- 974.

27. Darvall KA, Bate GR, Adam DJ, Silverman SH, Bradbury AW. Duplex ultrasound outcomes following ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy of symptomatic recurrent great saphenous varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:107- 114.

28. De Maeseneer MG. The role of postoperative neovascularisation in recurrence of varicose veins: from historical background to today’s evidence. Acta Chirurgica Belgica. 2004;104:281-287.

29. De Maeseneer MG, Ongena KP, Van den Brande F, Van Schil PE, De Hert SG, Eyskens EJ. Duplex ultrasound assessment of neovascularisation after saphenofemoral or saphenopoliteal junction ligation. Phlebology. 1997;12:64-68.

30. De Maeseneer MG, Tielliu IF, Van Schil PE, De Hert SG, Eyskens EJ. Clinical relevance of neovascularization on duplex ultrasound in long-term follow-up after varicose vein operation. Phlebology. 1999;14:118-122.

31. De Maeseneer MG, Giuliani DR, Van Schil PE, De Hert SG. Can interposition of a silicone implant after sapheno-femoral ligation prevent recurrent varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;24:445- 449.

32. De Maeseneer MG, Vandenbroeck CP, Van Schil PE. Silicone patch saphenoplasty to prevent repeat recurrence after surgery to treat recurrent saphenofemoral incompetence: Longterm follow-up study. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:98-105.

33. De Maeseneer MG. Recurrent varicose veins after surgery [thesis]. Antwerpen: Universiteit Antwerpen; 2005.

34. De Maeseneer MG, Vandenbroeck CP, Hendriks JM, Lauwers PR, Van Schil PE. Accuracy of duplex evaluation one year after varicose vein surgery to predict recurrence at the sapheno-femoral junction after five years. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29:308-312.

35. De Maeseneer M. Recurrence of varicose veins is usually defined as re-emergence of varicosities after previous surgery. Angeiologie. 2006;58:28-31.

36. De Maeseneer MG, Philipsen TE, Vandenbroeck CP, et al. Closure of the cribriform fascia: an efficient anatomical barrier against postoperative neovascularisation at the saphenofemoral junction? (A prospective study). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:361-366.

37. De Maeseneer M. Surgery for recurrent varicose veins: Toward a less-invasive approach? Perspect Vas Surg Endovasc Ther. 2011;23:244-249.

38. De Maeseneer MG, Cavezzi A. Etiology and pathophysiology of varicose vein recurrence at the saphenofemoral or saphenopopliteal junction: an update. Veins and Lymphatics. 2012;1:4.

39. De Maeseneer M, Pichot O, Cavezzi A, et al; Union Internationale de Phlebologie. Duplex ultrasound investigation of the veins of the lower limbs after treatment for varicose veins: UIP Consensus Document. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:89-102.

40. Edwards AG, Donaldson D, Bennets C, Mitchell DC. The outcome of recurrent varicose veins surgery: the patient’s perspective. Phlebology. 2005;20:57-59.

41. Egan B, Donnelly M, Bresnihan M, Tierney S, Feeley M. Neovascularization: An innocent bystander in recurrent varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1279-1284.

42. Elkaffas KH, Elkashef O, Elbaz W. Great saphenous vein radiofrequency ablation versus standard stripping in the management of primary varicose veinsa randomized clinical trial. Angiology. 2010;62:49-54.

43. El Wajeh Y, Giannoukas AD, Gulliford CJ, Suvarna SK, Chan P. Saphenofemoral venous channels associated with recurrent varicose veins are not neovascular. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;28:590-594.

44. Englund R. Duplex scanning for recurrent varicose veins. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66(9):618-620.

45. Farrah J, Shami SK. Patterns of incompetence in patients with recurrent varicose veins: a duplex ultrasound study. Phlebology. 2001;16:34-37.

46. Fassiadis N, Kianifard B, Holdstock JM, Whiteley MS. A novel approach to the treatment of recurrent varicose veins. Int Angiol. 2002;21(3):275-276.

47. Ferrara F, Bernbach HR. La sclérothérapie des varices récidivées. Phlébologie. 2005;58:147-150.

48. Fischer R, Chandler JG, De Maeseneer MG, et al. The unresolved problem of recurrent saphenofemoral reflux. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:80-94.

49. Fischer R, Linde N, Duff C, Jeanneret C, Chandler JG, Seeber P. Late recurrent saphenofemoral junction reflux after ligation and stripping of the greater saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:236-240.

50. Fischer R, Linde N, Duff C. Cure and reappearance of symptoms of varicose veins after stripping operation–A 34 year follow-up. J Phlebology. 2001;1:49-60.

51. Fischer R, Chandler JG, Stenger D, Puhan MA, De Maeseneer MG, Schimmelpfennig L. Patients characteristics and physician-determined variables affecting saphenofemoral reflex recurrence after ligation and stripping of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:81-87.

52. Frings N, Nelle A, Tran P, Fischer R, Krug W. Reduction of neoreflux after correctly performed ligation of the saphenofemoral junction. A randomized trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;28:246-252.

53. Gad MA, Saber A, Hoklam EN. Assessment of causes and patterns of recurrent varicose veins after surgery. North Am J Med Sci. 2012;4:45-48.

54. Gauw SA, Pronk P, Mooij MC, Gaastra MTW, Lawson JA, van Vlijmen-van Keulen CJ. Detection of varicose vein recurrence by duplex ultrasound: intra- and interobserver reproducibility. Phlebology. 2013;28:109-111.

55. Geier B, Stücker M, Hummel T, et al. Residual stumps associated with inguinal varicose vein recurrence: a multicenter study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:207-210.

56. Geier B, Olbrich S, Barbera L, Stücker M, Mumme A. Validity of the macroscopic identification of neovascularization at the saphenofemoral junction by the operating surgeon. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:64-68.

57. Geier B, Mumme A, Hummel T, Marpe B, Stücker M, Asciutto G. Validity of duplexultrasound in identifying the cause of groin recurrence after. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:968-972.

58. Gillet JL, Perrin M. Exploration echodoppler des récidives variqueuses postchirurgicales. Angéiologie. 2004;56:26- 31.

59. Gillet JL. Traitement des récidives chirurgicales de la jonction saphènofémorale et saphéno-poplitée par echosclérose. Phlébologie. 2003;56:241-245.

60. Gohel MS, Davies AH. Choosing between varicose vein treatments: looking beyond occlusion rates. Phlebology. 2008;23:51-52.

61. Haas E, Burkhardt T, Maile N. Recurrence rate by neovascularisation following a modification of long saphenous vein operation in the groin: a prospectived randomized duplex-ultrasound controlled study. Phlebologie. 2005;34:101-104.

62. Hamel-Desnos C, Ouvry P, Benigni JP, et al. Comparison of 1% and 3% polidocanol foam in ultrasound guided sclerotherapy of the great saphenous vein: A randomized, double-blind trial with 2 year-follow-up:The 3/1 study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:723-729.

63. Hartman K, Klode J, Pfister R, et al. Recurrent varicose veins: Sonographybased re-examination of 210 patients 14 years after ligation and saphenous stripping. VASA. 2006;35:21-26.

64. Hayden A, Holdsworth J. Complications following re-exploration of the groin for recurrent varicose veins. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83:272-273.

65. Heim D, Negri M, Schlegel U, De Maeseneer M. Resecting the great saphenous stump with endothelial inversion decreases neither neovascularization nor thigh varicosity recurrence. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:1028- 1032.

66. Hinchliffe RJ, Ubhi J, Beech A, Ellison J, Braithwaite BD. A prospective randomised controlled trial of VNUS Closure versus surgery for the treatment of recurrent long saphenous varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:212-218.

67. Jiang P, van Rij AM, Christie R, Hill G, Solomon C, Thomson I. Recurrent varicose veins: patterns of reflux and clinical severity. Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;7:322- 329.

68. Kakkos SK, Bountouroglou DG, Azzam M, Kalodiki E, Daskalopoulos M, Geroulakos G. Effectiveness and safety of ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy for recurrent varicose veins: immediate results. J Endovasc Ther. 2006;13:357-364.

69. Kalodiki E, Lattimer CR, Azzam M, Shawish E, Bountouroglou D, Geroulakos G. Long term results of a randomized controlled trial on ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy combined with sapheno-femoral ligation vs standard surgery for varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:451-457.

70. Kambal A, De’ath AD, Albon H, Watson A, Shandall A, Greenstein D. Endovenous laser ablation for persistent and recurrent venous ulcers after varicose vein surgery. Phlebology. 2008;23:193-195.

71. Kianifard B, Holdstock JM, Whiteley MS. Radiofrequency ablation (VNUS closure) does not cause neo-vascularisation at the groin at one year: results of a case controlled study. Surgeon. 2006;4:71-74.

72. Kostas T, Loannou CV, Toulouopakis E, et al. Recurrent varicose veins after surgery: A new appraisal of a common and complex problem in vascular surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2004;27:275-282.

73. Kostas TT , Ioannou CV, Veligrantakis M, Pagonidis C, Katsamouris AN. The appropriate length of great saphenous vein stripping should be based on the extent of reflux and not on the intent to avoid saphenous nerve injury. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:1234-1241.

74. Kofoed SC, Qvamme GM, Schroeder TV , Jakobsen BH. Causes of need for reoperation following surgery for varicose veins in Denmark. Ugeskr Laeger. 1999;8:779-783.

75. Labropoulos N, Touloupakis E, Giannoukas AD, Leon M, Katsamouris A, Nicolaides AN. Recurrent varicose veins: investigation of the pattern and extent of reflux with color flow duplex scanning. Surgery. 1996;119:406-409.

76. Labropoulos N, Bhatti A, Leon L, Borge M, Rodriguez H, Kalman P. Neovascularization after great saphenous ablation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:219-222.

77. Lane RJ, Cuzzilla ML, Coroneos JC, Phillips MN, Platt JT. Recurrence rates following external valvular stenting of the saphenofemoral junction: a contralateral stripping of the great saphenous vein. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:595- 603.

78. Leal Monedero J, Zubicoa Ezpeleta S, Castro Castro J, Calderon Ortiz M, Sellers Fernandez G. Embolization treatment of recurrent varices of pelvic origin. Phlebology. 2006;21:3-11.

79. Lemasle Ph, Lefebvre-Villardebo M, Uhl JF, Vin F, Baud JM. Récidive variqueuse postopératoire: et si la neovascularisation inguinale n’était que le développement d’un réseau pré-existant. Phlébologie. 2009:62:42-48.

80. Lurie F, Creton D, Eklof B, et al. Prospective randomized study of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration (Closure) versus ligation and vein stripping (EVOLV eS) two-year follow-up. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29:67- 73.

81. Lv W, Wu XJ, Collins M, Han ZL, Jin X. Analysis of a series of patients with varicose vein recurrence. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:1156-1165.

82. Mc Donagh B, Sorenson S, Gray C, et al. Clinical spectrum of recurrent postoperative varicose veins and efficacy of sclerotherapy management using the compass technique. Phlebology. 2003;18:173-185.

83. Menyhei G, Gyevnár Z, Arató E, Kelemen O, Kollár L. Conventional stripping versus cryostripping: a prospective randomised trial to compare improvement in quality of life and complications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:218-223.

84. Merchant RF, Pichot O; for the Closure study group. Long-term outcomes of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration of saphenous reflux as a treatment for superficial venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:502-509.

85. Mikati A. Indications et résultats de la ligature coelioscopique des veines perforantes incontinentes dans les récidives variqueuses compliquées. Phlébologie. 2010;63:59-67.

86. Milone M, Salvatore G, Maietta P, Sosa Fernandez LM, Milone F. Recurrent varicose veins of the lower limbs after surgery. Role of surgical technique (stripping vs. CHIVA ) and surgeon’s experience. G Chir. 2011;32:460-463. 87. Mouton WG, Bergner M, Zehnder T,

von Wattenwyl R, Naef M, Wagner HE. Recurrence after surgery for varices in the groin is not dependent on body mass index. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138(11- 12):186-188.

88. Nwaejike N, Srodon PD, Kyriakides C. Endovenous laser ablation for the treatment of recurrent varicose vein disease – A single centre experience. Int J Surg. 2010;8:299-301.

89. O’Hare JL, Parkin D, Vandenbroeck CP, Earnshaw JJ. Mid-term results of ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy for complicated and uncomplicated varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:109-113.

90. Parés JO, Juan J, Tellez R, et al. Varicose vein surgery. Stripping versus the CHIVA method: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2010;251:624-631.

91. Pavei P, Vecchiato M, Spreafico G, et al. Natural history of recurrent varices undergoing reintervention: a retrospective study. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:1676- 1682.

92. Perala J, Rautio T, Biancari F, et al. Radiofrequency endovenous obliteration versus stripping of the long saphenous vein in the management of primary varicose veins: 3-year outcome of a randomized study. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19: 669-72.

93. Perrin M. Recurrent varicose veins after surgery. Phlebolymphology. 31:14-20.

94. Perrin M. Recurrent varices after surgery. Hawaii medical journal. 2000;59:214- 216.

95. Perrin M, Labropoulos N, Leon LR. Presentation of the patient with recurrent varices after surgery (REVA S). J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:27-34.

96. Perrin M, Gillet JM. Management of recurrent varices at the politeal fossa after surgical treatment. Phlebology. 2008:23:64-68.

97. Perrin M. Le profil du patient REVA S: résultats d’une enquête internationale. Angéiologie. 2006;58:44-45.

98. Perrin M, Allaert, FA. Intra-and interobserver reproducibility o the recurrent varicose veins after surgery (REVA S) classification. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;32:326-333.

99. Perrin M, Gillet JL. Récidive de varices à l’aine et à la fosse poplitée après traitement chirurgical. J Mal Vasc. 2006;31:236-246.

100. Pittaluga P, Chastanet S, Locret T, Rousset O. Retrospective evaluation of the need of a surgery at the groin for the surgical treatment of varicose vein. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:1442-1450.

101. Pourhassan S, Zarras K, Mackrodt HG, Stock W. Recurrent varicose veins. Surgical procedure-results. Zentralbl Chir. 2001;126(7):522-525.

102. Proebstle TM, Aim J, Göckeritz O, et al; European Closure Fast Clinical Study Group. Three-year European follow-up of endovenous radiofrequency-powered segmental thermal ablation of the great saphenous vein with or without treatment of calf varicosities. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:146-152.

103. Pronk P, Gauw SA, Mooij MC, et al. Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing Sapheno-Femoral Ligation and Stripping of the Great Saphenous Vein with Endovenous Laser Ablation (980 nm) Using Local Tumescent Anaesthesia: One Year Results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40:649-656.

104. Rabe E, Pannier F, Ko A, Berboth G, Hoffmann B, Hertel S. Incidence of varicose veins, chronic venous insufficiency, and progression of the disease in the Bonn Vein Study II. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:791.

105. Rashid HI, Ajeel A, Tyrrell MR. Persistent popliteal fossa reflux following saphenopopliteal disconnection. Br J Surg. 2002;89:748-751.

106. Reich-Schupke S, Mumme A, Altmeyer P, Stuecker M. Expression with stump recurrence and neovascularization after varicose vein surgery a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:480-485.

107. Rass K, Frings N, Glowack P, et al. Comparable effectiveness of endovenous laser ablation and high ligation with stripping of the great saphenous vein. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:49-58.

108. Rasmussen LH, Bjoern L, Lawaetz M, Lawaetz B, Blemings A, Eklöf B. Randomized trial comparing endovenous laser ablation with stripping of the great saphenous vein: clinical outcome and recurrence after 2 years. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;39:630-635.

109. Rasmussen LH, Lawaetz M, Bjoern L, Vennits B, Blemings A, Eklof B. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, foam sclerotherapy and surgical stripping for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1079-1087.

110. Rasmussen L, Lawaetz M, Bjoern L, Blemings A, Eklof B. Randomized trial comparing endovenous laser ablation and stripping of the great saphenous vein with clinical and duplex outcome after 5-years. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(2):421-426.

111. Rasmussen LA , Lawaetz M, Bjoern L, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, foam sclerotherapy and surgical stripping for great saphenous varicose veins with 3-year follow-up. J Vasc Surg: Venous and Lym Dis. 2013;1:349-356.

112. Raussi M, Pakkanen J, Varlia E, Kupi H, Saarinen J. Transilluminated powered phlebectomy in the treatment of primary and recurrent varicose disease: sixmonth follow-up of 135 legs. Phlebology. 2006;21:110-114.

113. Rewerk S, Noppeney T, Winkler M, et al. Pathogenese der Primär- und Rezidivvarikosis an der Magna-Krosse (Die Rolle von VEGF und VEGF-Rezeptor). Phlebologie. 2007;36:137-142.

114. Roka F, Binder M, Bohler-Sommeregger K. Mid-term recurrence rate of incompetent perforating veins after combined superficial vein surgery and subfascial endoscopic perforating vein surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(2):359-363.

115. Rutgers PH, Kitslaar PJ. Randomized trial of stripping versus high ligation combined with sclerotherapy in the treatment of the incompetent greater saphenous vein. Am J Surg. 1994;168:311-315.

116. Rutherford EE, Kianifard B, Cook SJ, Holdstock JM, Whiteley MS. Incompetent perforating veins are associated with recurrent varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;21:458-460.

117. Saarinen J, Suominen V, Heikinen M, et al. The profile of leg symptoms, clinical disability and reflux in legs with previously operated varices. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:51-55.

118. Shadid N, Ceulen R, Nelemans P, et al. Randomized clinical trial of ultrasoundguided foam sclerotherapy versus surgery for the incompetent great saphenous vein. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1062-1070.

119. Stonebridge P, Chalmers N, Beggs I. Recurrent varicose veins: a varicographic analysis leading to a new practical classification. Br J Surg. 1995;82:60-62.

120. Stötter L, Schaaf I, Bockelbrink A. Comparative outcomes of radiofrequency endoluminal ablation, invagination stripping and cryostripping in the treatment of great saphenous vein. Phlebology. 2006;21:60-64.

121. Stücker M, Netz K, Breuckmann F, Altmeyer P, Mumme A. Histomorphologic classification of recurrent saphenofemoral reflux. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:816-822.

122. Klem TM, Schnater JM, Schütte PR, Hop W, van der Ham AC, Wittens CH. A randomized trial of cryo stripping versus conventional stripping of the great saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:403-439.

123. Theivacumar NS, Dellagrammaticas D, Darwood RJ, Mavor AI, Gough MJ. Fate of the great saphenous vein following endovenous laser ablation: does recanalisation mean recurrence. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:211-215.

124. Theivacumar NS, Darwwod R, Gough MJ. Neovascularisation and recurrence 2 years after varicose vein treatment for sapheno-femoral and great saphenous vein reflux: a comparison of surgery and endovenous laser ablation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:203-207.

125. Theivacumar NS, Gough MJ. Endovenous laser ablation (EVLA ) to treat recurrent varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41:691-696.

126. Tsang FJ, Davis M, Davies AH. Incomplete saphenopopliteal ligation after short saphenous vein surgery: a summation analysis. Phlebology. 2005;20:106-109.

127. Turton EPL, Scott DJA, Richards SP, et al. Duplex derived evidence of reflux after varicose vein surgery: neo reflux or neovascularisation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;17:230-233.

128. Theivacumar NS, Gough MJ. Endovenous Laser Ablation (EVLA ) to Treat Recurrent Varicose Veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41:691-696.

129. van Groenendael L, van der Vliet A, Flinkenflögel L, et al. Treatment of recurrent varicose veins of the great saphenous vein by conventional surgery and endovenous laser. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:1106-1113.

130. van Groenendael L, van der Vliet JA, Flinkenflögel L, Roovers EA, van Sterkenburg SM, Reijnen MM. Conventional surgery and endovenous laser ablation of recurrent varicose veins of the small saphenous vein: A retrospective clinical comparison and assessment of patient satisfaction. Phlebology. 2010;25(3):151-157.

131. van Neer P, Kessels A, de Haan E, et al. Residual varicose veins below the knee are not related to incompetent perforating veins. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1051-1054.

132. van Neer P, de Haan MW, de Veraart JCJM, Neumann HAM. Recurrent varicose veins below the knee after varicose vein surgery. Phlebologie. 2007;36:132-136.

133. van Rij AM, Jiang P, Solomon C, Christie RA, Hill GB. Recurrence after varicose vein surgery: a prospective long-term clinical study with duplex ultrasound scanning and air plethysmography. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:935-943.

134. van Rij AM, Jones GT, Hill GB, Jiang P. Neovascularization and recurrent varicose veins : More histologic and ultrasound evidence. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40: 296-302.

135. Vin F, Chleir F. Aspect échographique des récidives variqueuses postopératoires du territoire de la veine petite saphène. Ann Chir. 2001;126:320-324.

136. Winterborn RJ, Foy C, Earnshaw JJ. Causes of varicose vein recurrence: Late results of a randomized controlled trial of stripping the long saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:634-639.

137. Winterborn RJ, Earnshaw JJ. Randomised trial of polytetrafluoroethylene patch insertion for recurrent great saphenous varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:367-373.

138. Wong JKF, Duncan JL, Nichols DM. Whole-leg duplex mapping for varicose veins: Observation on patterns of reflux in recurrent and primary legs, with clinical correlation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;25:267-275.

139. Wright D, Rose KG, Young E, McCollum CN. Recurrence following varicose vein surgery. Phlebology. 2002;16:101-105.

140. Wright D, Gobin JP, Bradbury AW, et al; The Varisolve® European Phase III Investigators Group. Varisolve® polidocanol microfoam compared with surgery or sclerotherapy in the management of varicose veins in the presence of trunk vein incompetence: European randomized controlled trial. Phlebology. 2006;21:180-190.

141. Zan S, Varetto G, Maselli M, Scovazzi P, Moniaci D, Lazzaro D. Recurrent varices after internal saphenectomy: Physiopathological hypothesis and clinical approach. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2003;51(1):79-86.

142. Franceschi C. ‘Theorie et Pratique de la Cure Conservatrice et Hémodynamique de l’Insuffisance Veineuse en Ambulatoire’ Precy-sous-Thil: Editions de l’Armancon, 1988.

143. Pittaluga P, Chastanet, Rea B, et al. Midterm results of the surgical treatment of varices by phlebectomy with conservation of a refluxing saphenous vein. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:107-118.

144. Pittaluga P, Chastanet S, Rea B, Barbe R. The effect of isolated phlebectomy on reflux and diameter of the great saphenous vein: A prospective study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40:122-128.

145. Eklof B, Perrin M, Delis KT, Rutherford RB, Gloviczki P; American Venous Forum; European Venous Forum; International Union of Phlebology; American College of Phlebology; International Union of Angiology. Updated terminology of chronic venous disorders: the VEIN-TERM transatlantic interdisciplinary consensus document. J Vasc Surg. 2009;48:498- 501.

146. Campanello M, Hammarsten J, Forsberg C, Bernland P, Henrikson O, Jensen J. Standard stripping versus long saphenous vein saving surgery for primary varicose veins: a prospective, randomized study with the patients as their own controls. Phebology. 1996;11:45-49.

147. Einarsson E, Eklof B, Neglén P. Sclerotherapy or surgery as treatment for varicose veins. A prospective randomized study. Phlebology. 1993;8:22-26.

148. Hobbs JT. Surgery and sclerotherapy in the treatment varicose veins: a 6-year random trial. Arch Surg. 1974;109:793- 796.

149. Hobbs JT. Surgery or sclerotherapy for varicose veins: 10year results of a random trial. Lancet. 1978;27:1149.

150. Dwerryhouse S, Davies B, Harradine K, Earnshaw JJ. Stripping the long saphenous vein reduces the rate of reoperation for recurrent varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 1999;29:589-592.

151. Pittaluga P, Chastanet S, Guex JJ. Great saphenous vein stripping with preservation of sapheno-femoral confluence: hemodynamic and clinical results. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:1300-1305.

152. Glass GM. Neovascularization in recurrence of varices of the great saphenous vein in the groin: phlebography. Angiology. 1988;39:577- 582.

153. Jones L, Braithwaite BD, Selwyn D, Cooke S, Earnshaw JJ. Neovascularisation is the principal cause of varicose vein recurrence: results of a randomised trial of stripping the long saphenous vein. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;12:442-445.

154. Nyamekye I, Shephard NA, Davies B, Heather BP, Earnshaw JJ. Clinicopathological evidence that neovascularisation is a cause of recurrent varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1998;15:412-415.

155. Kostas T, Ioannou CV, Drygiiannakis I, et al. Chronic venous disease progression and modification of predisposing factors. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:900-907.

156. Krysa J, Jones GT, van Rij AM. Evidence for a genetic role in varicose veins and chronic venous insufficiency. Phlebology. 2012;27:329-335.