An American Surgeon in Paris – A brief report from a Servier Traveling Fellow

Brian KNIPP

Ann Arbor, MI, USA

INTRODUCTION

As the plane touched down on the tarmac at the Istanbul Ataturk airport, I realized that my horizons had just broadened substantially. Born in the central United States, I had rarely ventured beyond our nation’s borders. Yet here I sat in Turkey, my body unsure of what time it was, or what time even meant, anticipating new vistas and experiences. We were transported to the Hotel Marmara, a beautiful edifice in the commercial district of Istanbul on Taksim Square, a short cab ride from several of the most stunning sights in the city. We toured the Aya Sofia, a huge museum which started its life in 537 A.D. as a Christian basilica, subsequently became a mosque in 1453 after the capture of Istanbul by the Ottoman Turks, and finally became a museum in 1935 after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. We also entered the Blue Mosque, built between 1609 and 1616, and the Basilica Cisterns, a fantastic underground grotto full of the shadows of Roman architecture.

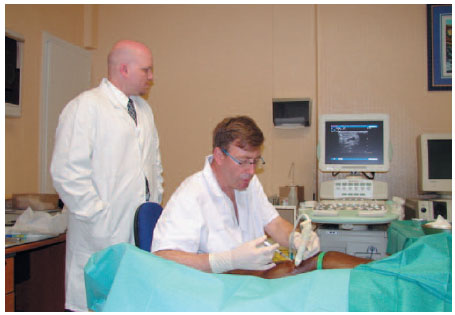

Working with Dr Jean-Luc Gerard in Paris.

Trips to bazaars, rug shops, and street cafés highlighted our stay in the city.

The meeting began with a beautiful dinner at the top of our hotel. Classic Middle Eastern cuisine and wine highlighted an evening spent meeting our European and Turkish counterparts. The next morning, the presentations commenced. While a notable percentage were in tongues I was unfamiliar with, I was still able to glean a great deal from them. Discussions involved prevention, epidemiology, and treatment of superficial and deep venous disease as well as venous thromboembolism. I found the presentations excellent and informative. My colleague Reagan and I presented our research on the outcomes of primary repair of traumatic venous injuries and factors predictive of poor outcome for deep venous stenting, respectively. Our presentations were both very well received; it was notable how much more lively the post-presentation discussions were at this meeting than at meetings I have attended in the United States.

At the conclusion of the meeting, we boarded a plane for Paris. We checked into our hotel in the 3rd district, one block from the Seine and within easy walking distance of Notre Dame Cathedral. We had no meetings scheduled that evening, so we sought out a local eatery, eschewing the touristy locations in favor of something an average Parisian might frequent. Fortunately, years of French lessons were not completely in vain. We found a small diner and ordered an excellent meal. The staff were extremely friendly and made our experience memorable.

The next morning, we were met at our hotel by a tour guide and chauffeur. We were given free rein to see whatever sights interested us. We toured the Place des Vosges, Notre Dame, the Sacre Coeur on Montmartre, and visited the Arc de Triomphe and Napoleon’s tomb at the Military Hospital. We briefly stopped at the Louvre, long enough to view the Mona Lisa, the Nike of Samothrace, and the Venus de Milo, as well as a few other notable exhibits. It was a breathtaking whirlwind tour through a city whose very cobblestones are steeped in hundreds of years of history.

Dinner that evening was on the top floor of the new Museum of Nature, located a stone’s throw from the Eiffel Tower. We had an excellent meal with our Servier hosts, and we had the opportunity to meet two of the surgeons who would be allowing us to observe their practice over the next two days, Dr Jean-Luc Gerard and Dr Christian Lebard. It was a very enjoyable evening topped off by the fact that my courageous traveling partner chose the calf’s head salad (“la tête de veau” en français, which gives a great deal of elegance to a dish that most Americans would have difficulty with).

The next morning we were transported to the Servier offices and laboratories where Françoise had arranged a tour and several presentations for us. We had the opportunity to see what major pharmaceutical and basic applications research projects their scientists are currently engaged in. Targeted molecular therapy for chronic venous disease was the major topic. It was very enjoyable meeting with these bright individuals. Their research efforts parallel many of those I have been involved with in our own academic research laboratories.

After a very pleasant lunch with our hosts, we were taken to the offices of Dr Jean-Luc Gerard, an angiologist who practices vascular interventions in addition to medical management of venous disease. He had several patients scheduled that morning and allowed us to observe his practice of endovenous laser ablation. I was impressed at his ability to achieve adequate analgesia for these patients who were being treated without general anesthesia. His rationale was that, first, it was far more convenient for the patients.

But more importantly, he contended that general anesthesia has a peripheral vasodilatory effect which serves to decrease the contact of the vessel with the laser catheter, decreasing the utility of the technique. I found this viewpoint interesting and contradictory to our practice; I was, however, unfortunately unable to find any literature to support or refute this position. His final argument regarding the superiority of local anesthesia was the immediate feedback regarding potential damage to the superficial nerves, an issue highly relevant when performing laser ablation of the lesser saphenous vein. The next morning, we arrived at the Clinique Internationale du Parc Monceau, where we met with Dr Christian Lebard. We spent the morning with him observing his use of radiofrequency ablation of several saphenous veins. He made use of the VNUS FASTCLOSURE system. While it is true that, historically, time requirements have been substantial for RF delivery systems, as high as 45 minutes per leg, the FASTCLOSURE system requires a fraction of that, with speeds equaling that of laser ablation. At this point, there seems to be no evidence in the literature to support the use of one technology over the other. My observations would suggest parity and that it is truly operator preference which should dictate choice of modality.

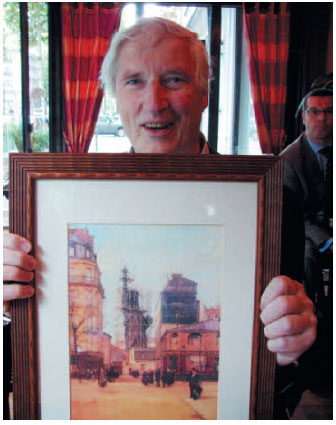

At the conclusion of his cases for the day, Dr Lebard escorted us to Le Vigny, a small café one block from the hospital. At our arrival that morning, he had pointed out the Statue of Liberty scale model in the entrance foyer to his hospital. I did not realize the significance of this model, however, until we were seated at the café and he handed us a photo from the wall which showed a view up the street to his hospital. In the photo, in place of his hospital a scaffold stood guarding the not-yet-complete Statue of Liberty. We had been standing at the birthplace of the Statue herself. What an exciting realization!

Dr Christian Lebard holding the photo of the birthplace of the Statue of Liberty at the restaurant Le Vigny.

Our visit was not about to slow down. After lunch, we boarded a train and headed south for Lyon. Once we arrived in the station, we found our way to the taxi stand. As our bags were being loaded into the trunk, I told the driver, in my best broken French, that we would like to go to the Radisson. The driver looked at me with a mixture of puzzlement and amusement, and replied “Bien sûr.” Off we went. For one block. I finally understood our driver’s amusement. To his credit, he was very professional and only charged us a meager fee. The hotel, I discovered later, is the tallest hotel in Europe, in a city where a building over three stories is noteworthy.

That evening, Dr Michel Perrin and Dr Philippe Nicolini took us to dinner at Au Petit Bouchon in downtown Lyon. Dr Perrin explained that the name meant “the little cork” and came from a time when patrons of the restaurant would order bottles of wine and hide them under the table. The clever restaurateurs would then simply hold the corks for each table as a means to correctly charge them for their wine purchases. I could not tell if Dr Perrin was in earnest or whether he was sporting with me. In either case, our dinner and entire experience were fantastic. After dinner, Dr Nicolini showed us some of the sights of Lyon. The highlight in my mind was the Basilique Notre-Dame de Fourvière, a powerful and beautiful basilica built on top of the Hill Fourvière and visible from all over Lyon.

From left to right: B. Knipp, P. Nicolini, R. Quan.

The next morning we met Dr Nicolini at La Clinique du Grand Large, and observed several of his cases, including an attempted inferior vena cava recanalization which unfortunately was unsuccessful despite heroic efforts to traverse the occlusion from above and below. He completed the day with a couple cases of vascular embolizations for pelvic congestion syndrome.

With Dr Nicolini in Lyon.

After our morning at the clinic, we boarded a train again for Marseilles. It was a very good thing that I had had several days to hone my nascent French skills, as I quickly discovered that, in the south of France, English is extremely uncommon. The primary language in addition to French is Italian. Dinner that night was at the Vieux Port, the hotel’s restaurant as the guests of Dr Olivier Hartung and Dr Yves Alimi. The food was excellent, and I had the opportunity to sample pastis, a derivative of absinthe. When mixed with water, this clear alcohol becomes a milky white color and is reminiscent of licorice. It is synonymous with southeastern France, and a truly delicious drink. After dinner, our wives met us in our rooms and we shared drinks on our balcony overlooking the harbor.

Notre-Dame de Fourvière

The next morning, we met Dr Hartung at the North Hospital where we had the opportunity to do the rounds with his team. We then went to the operating room and observed several interventional cases, primarily managing pelvic congestion syndrome via embolization. At the conclusion of the day in the operating room, we returned to the train station for our trip back to Paris.

The next morning, we met Dr Hartung at the North Hospital where we had the opportunity to do the rounds with his team. We then went to the operating room and observed several interventional cases, primarily managing pelvic congestion syndrome via embolization. At the conclusion of the day in the operating room, we returned to the train station for our trip back to Paris.

n rounds with the team in Marseilles.

Once back in Paris, we took our leave of Reagan and his wife, who were headed for a personal side trip to Versailles and Normandy. My wife and I had a late dinner that evening overlooking the Seine and the Eiffel Tower, followed the next day by a dinner cruise on the Seine.

The thing I ask myself now is what has become of this opportunity? It was a trip of a lifetime, to be sure, but how has it impacted my career? As a surgical resident, do I have the background and experience to make use of the lessons provided me? Those answers took months to develop. But as I conversed recently with one of the pioneers in superficial and deep venous surgery, carrying on a conversation about the intricacies of this field, I realized how much more I had been given than just a collection of beautiful photographs. The practices and philosophies of vascular surgeons throughout the world have been mine to directly observe, to consider, and in some cases accept and in other cases to respectfully disagree with. For a resident with a strong interest in vascular surgery, no amount of sightseeing, while pleasurable, will be as valuable as these insights. I am extremely grateful to everyone who made this trip possible. To Director Françoise Pitsch for supporting and organizing the trip.

Brian Knipp, Olivier Hartung, Reagan Quan

To Sabrina Fadda for coordinating our travels, and ensuring that our dinners were delectable and our nights restful. To Dr Perrin for overseeing our trip and taking time out of his busy schedule to meet with us on several occasions. To everyone else that made this trip possible. And to the Servier company for supporting the trip. I hope that in the future their return on investment will be substantial.

Merci. Merci beaucoup, mes amis.

ERRATUM

In the previous issue of Phlebolymphology (2008;15;1:37-39), Reagan Quan’s report of the AVF/Servier Traveling Fellowship contained erroneous information. Contrary to what was indicated, Dr Jean-Luc Gérard uses a 1470 nm laser and not a 1024 nm laser, and Aethoxisclerol® (polidocanol) not Actetaxol. Our apologies to Dr Gérard.