The Essentials from the XVIIth World Meeting of the Union Internationale de Phlébologie, 7-14 September 2013, Boston, USA

VENOUS SYMPTOMS

AND CHRONIC VENOUS DISEASE

Whether venous symptoms form part of chronic venous disease (CVD) was the first question asked in the MPFF at a dose of 500 mg symposium organized under the framework of the ‘Union Internationale de Phlébologie’ (UIP) in Boston. This remains a controversial question. For some patients, lower limb pain is poorly related to the presence of varicose veins,1-3 C-class of the Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, Pathophysiological (CEAP) classification,4 degree of reflux,5 or to the presence of inflammatory markers.6 In contrast, other patients may have a significant correlation between lower limb pain/ symptoms and worsening clinical signs of CVD or CEAP clinical classes.7-12

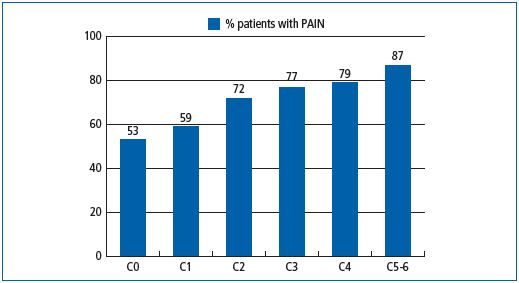

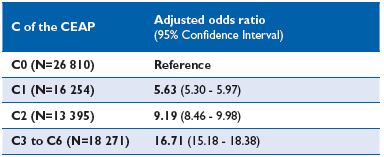

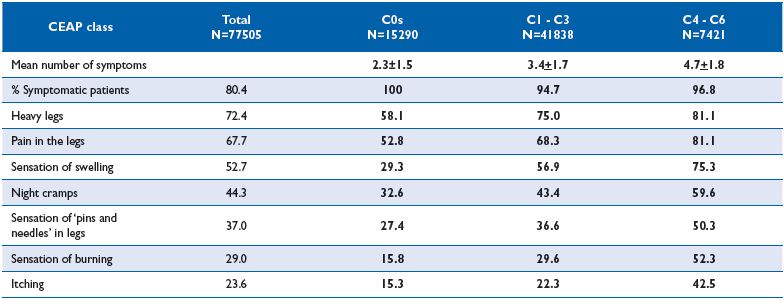

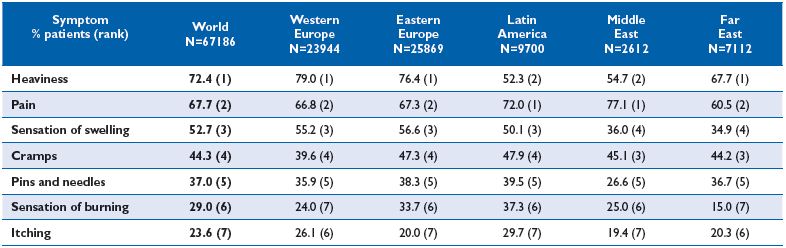

In the recent Vein Consult Program (VCP), which was performed in 22 countries and gathered information on 95 000 subjects screened by general practitioners (GPs) for CVD, positive correlations between increasing CEAP clinical classes and the presence of pain were observed (Figure 1). When adjusted for age, gender and body mass index, the multivariate analysis in the VCP showed that the occurrence of venous symptoms was clearly linkedto clinical CEAP class (Table I). The risk for developing symptoms increased significantly with disease severity. Individuals with a chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) classification C3-C6 were 16-fold more likely to be symptomatic than individuals in C0. When considering individual symptoms according to CEAP clinical class, ‘heaviness’ and ‘sensation of swelling’ appeared more related to the C3 class (edema), while itching was related to skin changes (Table II). The prevalence ofsymptoms in the VCP was high in all geographical areas studied. Moreover, distribution of symptom prevalence (by decreasing frequency: heavy legs, pain, sensation of swelling, night cramps, etc) was similar whatever the area considered. This suggests that perception of pain is similar in all countries studied and is likely to be disconnected from any cultural phenomenon (Table III).

Figure 1. Frequency of venous pain in subjects participating in the Vein Consult

Program according to clinical class of the CEAP classification.13

Table I. Independent risk factors for venous symptom occurrence

in the multivariate analysis of the Vein Consult Program (VCP)

Table II. Distribution of the prevalence of CVD symptoms according to CEAP class

Table III. Frequency of venous symptoms according to geographical areas surveyed in the Vein Consult Program.

In the literature, the presence of symptoms attributed to venous pain correlates with worse quality of life (QOL).4

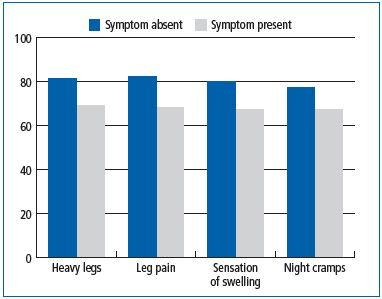

This was also found in subjects participating in the VCP and individuals with venous symptoms had a lower global index score (GIS) than those without symptoms, indicating a worse QOL for patients complaining of pain in their lower limbs (Figure 2).

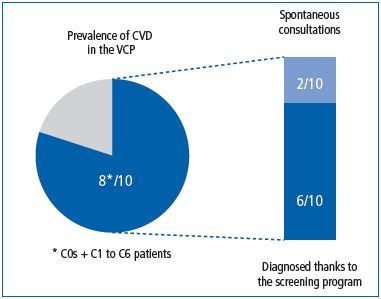

Globally, 63% of screened subjects in the VCP were considered to have CVD by their GPs.13 Subjects with symptoms only (C0s class) were less likely to be considered as having CVD and to be liable for treatment than those with signs. The presence of a symptom was not the trigger for starting CVD treatment. While 63% of screened subjects were considered to have CVD by GPs, only 22% (one-third) were referred to venous specialists. Referral to a venous specialist was associated with severity of disease, as this increases with higher clinical CEAP class from 4% in C0s to 60% in C6. It is not until severe stages are present that GPs refer their patients to a venous specialist. Despite this, it appears that a systematic search for venous symptoms, as was performed in the VCP, could help detect CVD in 6 out of 10 subjects (it is of note that 50% of these were C0s or C1s). Only 2 out of 10 subjects spontaneously sought help for their venous problems13 (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Quality of life assessment in subjects participating in

the Vein Consult Program according to the presence or absence of

venous symptoms (C0s to C6 patients; N=35495)

Figure 3. Prevalence of symptomatic subjects and percentage of

subjects consulting spontaneously for leg complaints in the Vein

Consult Program

These facts raise the question of why venous symptoms are so often overlooked. The underestimation of venous pain and symptoms may have multiple causes, such as:

• They mostly affect women.

• They are not specific for venous disease.

• They are subjective per se and not systematically related to clinical signs or reflux.

• They are very common whatever the geographical area.

• Improvements are more important for the patient than the physician.

In conclusion, venous pain should be considered a part of CVD as a systematic search for symptoms may help detect the disease, and relief of symptoms leads to improvements in QOL, which is meaningful to patients.

WHAT IS THE BURDEN OF CHRONIC VENOUS DISEASE FOR SOCIETEY?

CVD is a very common disease among adults and is estimated to be the seventh most common reason for physician referral in the US. Approximately 1% of the adult population has an ulcer of venous origin at any one time with 4% at risk. Venous ulcers are often lengthy medical problems and can last for several years and are associated with high recurrence rates.14

In the VCP, subjects diagnosed with CVD after GP examination were requested to complete a self-administered questionnaire reporting features about their professional activities and QOL (using CIVIQ-14 and scoring 0 for a poor QOL to 100 for a very good QOL).

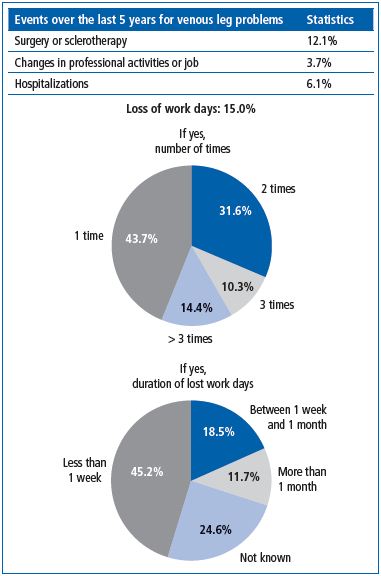

A total of 35 495 questionnaires from 17 countries (Armenia, Colombia, France, Georgia, Hungary, Indonesia, Mexico, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, Thaïland, UAE, Ukraine, Venezuela) were analyzed. Seven percent of patients had been hospitalized and 4% had changed their professional activities because of CVD. Loss of work days was reported in 15% of patients (Figure 4). The number of lost work days did not exceed 1 week for most (40%), while 33% had lost more (21% > 1 week and 12% > 1 month). QOL scores decreased with higher frequency of lost work days (from 68.5 ±19.5 for 1 time to 51.2 ± 22.9 for >3 times) and with duration of absence from work (from 76.0 ± 18.7 for <1 week to 55.3 ± 22.8 for >1 month). This was also true with increasing severity of CVD, ranging from 80.5 ± 16.4 in patients with telangiectasias to 54.8 ± 22.4 in those with an ulcer, and with presence of CVD symptoms: GIS was 84.0 ±16.5 in patients without pain versus 67.8 ± 19.9 in those with pain (unpublished data).

Figure 4. Appraisal of the costs of chronic venous disorders in

the Vein Consult Program

SPECIFIC TOOLS FOR ASSESSING QUALITY OF LIFE IN CVD

The use of comprehensive QOL instruments has shown greater consistency of results than those drawn from simple reporting of individual symptoms. A review of the literature shows that CVD is associated with reduced QOL, particularly in relation to pain, physical functioning and mobility, and also with negative emotional reactions and social isolation.15 Patients with varicose veins have reduced QOL compared with the general population,16,17 and treatment with surgery18,19 or sclerotherapy20 has been shown to improve QOL. However, it is important to distinguish the contribution of the varicose veins themselves from that of other concomitant manifestations of CVD.17

A large-scale study in 2404 patients that used the generic SF-36 questionnaire found significant associations between QOL and CVD, which was assessed by visual inspection and by ultrasonography. Worsening of QOL was proportional to disease severity.21

A multivariate analysis has shown that QOL (assessed with the disease-specific QOL scale CIVIQ-20) of patients with CVD depends mainly on symptoms, and is less affected by the presence of reflux, the CEAP class to which the patient is assigned, the patient’s age, body mass index, or duration of disease.22

Early symptomatic treatment, for example with MPFF at a dose of 500 mg, is aimed at alleviating CVD symptoms, which are now acknowledged to reduce QOL and handicap patients’ daily lives.

IS PAIN REDUCTION A MEANINGFUL TREATMENT OUTCOME?

According to Peter Neglen (Cyprus) and colleagues, the importance of targeting pain in the treatment of chronic venous disorders is emphasized by the fact that the CEAP classification, the Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS) and hemodynamic parameters are not sufficient assessment methods to judge the success of a treatment.4 Yet these methods are often the only ones used by Insurance Companies to reimburse venous treatments in certain countries.4

Patient-reported symptoms, in particular pain, and their assessment with QOL scales such as CIVIQ might be the best way to consider the value and the benefit of a treatment.

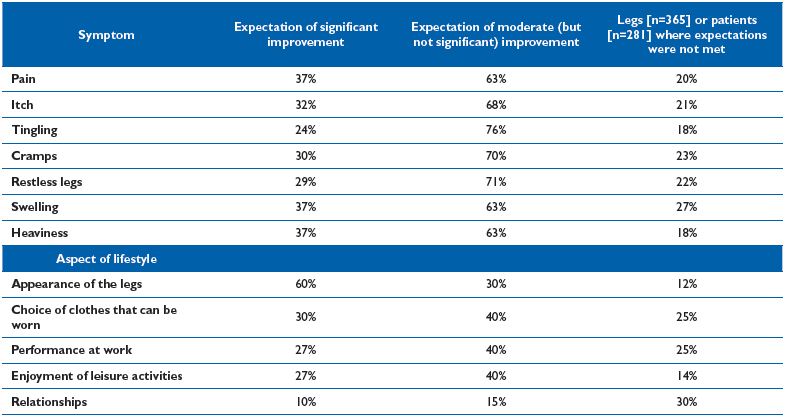

Table IV. Percentage of legs [n=373] or patients [n=281] associated with pre-operatively expectations of significant or moderate

improvement in symptoms and lifestyle respectively, and where expectations were not met 6 months post-operatively.24

This consideration is reinforced by patient expectations from treatment. For patients affected by CVD, treatment must be highly effective in terms of improving and even eradicating symptoms.23-25

According to previous studies, 75% to 100% of patients expect improvements in symptoms and lifestyle, and only 20% of patients in one study did not have their high expectations met.24 (Table IV)

Expectations for improvements in lifestyle are also high, with around 70% expecting improvements in the choice of clothes, enjoyment of leisure activities and performance at work, and 25% expecting an improvement in relationships.25 Patients also associated CVD with a high risk of morbidity. DVT and ulceration were deemed probable events by patients, and some patients also believed gangrene was a very high risk.25

All these CVD-related expectations and fears need to be addressed by providing clear information and by choosing adequate treatment. This is in line with the recommendations drawn from the VCP. Venoactive drugs have a place in the treatment strategy for CVD.

THE PLACE OF MPFF at a dose of 500 mg IN THE TREATMENT STRATEGY TO REDUCE SYMPTOMS IN CVD

MPFF at a dose of 500 mg has a number of vein-specific anti-inflammatory effects that relieve symptoms at all stages of CVD. In several placebo-controlled trials, micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF; MPFF at a dose of 500 mg) was associated with a significantly greater improvement in many of the symptoms of CVD after 2 months compared with placebo (P<0.001 MPFF vs placebo) or nonmicronized diosmin (P<0.05 MPFF vs simple diosmin). Importantly, symptom relief with MPFF was achieved rapidly and maintained in the long term.26

In a meta-analysis of 459 patients, MPFF significantly reduced the symptoms associated with venous ulcers after 4 and 6 months of treatment.27 MPFF is also beneficial for post-surgery pain,28,29 and pain associated with pelvic congestion syndrome.20 Patients receiving MPFF 2 weeks before and continuing for 14 days after varicose vein surgery required significantly less analgesic use than a control group.28,29 In a cross-over study, women were randomized to receive either MPFF or placebo. After 6 months, mean pain scores were significantly lower in the MPFF group compared with placebo (P<0.05).30

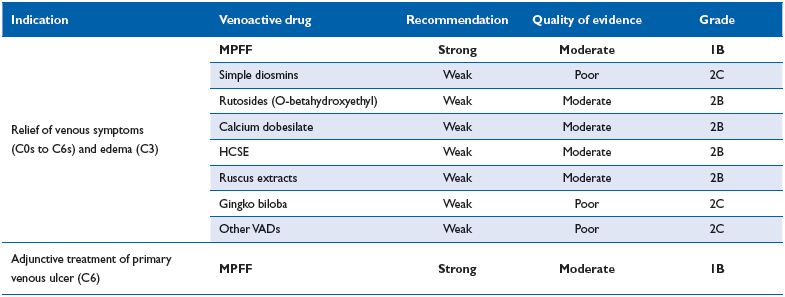

Table V. Recommendations for venoactive drugs from the international consensus meeting in Cyprus, November 2012.

PLACE OF MPFF at a dose of 500 mg IN RECENT INTERNATIONAL GUIDELINES

In recent guidelines for the management of CVD, MPFF at a dose of 500 mg has been assigned a high level of recommendation as a first-line treatment for venous symptoms at any stage of CVD.14 Recommendations for the use of venoactive drugs in the guidelines are based on the ‘Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (GRADE) system.31,32 The GRADE system differs from other schemes described in the guidelines in that separate levels are assigned for the recommendation for treatment and for the quality of evidence on which the recommendation is based. Recommendations are classified as either strong (grade 1) or weak (grade 2), and quality of evidence as high (grade A), moderate (grade B) or low (grade C). Importantly, the GRADE system recognizes that large observational studies may provide evidence of moderate or even high quality, particularly if the estimate of the magnitude of the treatment effect is very large.

Recommendations are summarized in Table V. It should be noted that the recommendation for MPFF at a dose of 500 mg is strong, based on benefits that clearly outweigh the risks and evidence of moderate quality (grade 1B) for the indication of relief of venous symptoms in C0s to C6s patients, including those with CVD-related edema. MPFF at a dose of 500 mg retains its strong recommendation for use as adjunctive therapy in treating venous ulcers.14

Venoactive drugs may be the only alternative available when patients cannot comply with compression therapy. In patients with CVD complications, venoactive drugs–and in particular MPFF at a dose of 500 mg–may be used in conjunction with sclerotherapy, surgery and/or compression therapy, and be considered as adjunctive therapy in patients with active venous ulcers, especially in those with large ulcers of long standing.14

1. Bradbury A, Evans C, Allan P, Lee A, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FG. What are the symptoms of varicose veins? Edinburgh vein study cross sectional population survey. BMJ. 1999;318:353- 356.

2. Duque MI, Yosipovitch G, Chan YH, Smith R, Levy P. Itch, pain, and burning sensation are common symptoms in mild to moderate chronic venous insufficiency with an impact on quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:504-508.

3. Kroger K, Ose C, Rudofsky G, Roesener J, Hirche H. Symptoms in individuals with small cutaneous veins. Vasc Med. 2002;7:13-17.

4. Darvall, KA, Bate GR, Adam DJ, Bradbury AW. Generic health-related quality of life is significantly worse in varicose vein patients with lower limb symptoms independent of CEAP clinical grade. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44:341-344.

5. Bradbury A, Evans CJ, Allan P, Lee AJ, Ruckley CV, Fowkes FG. The relationship between lower limb symptoms and superficial and deep venous reflux on duplex ultrasonography: The Edinburgh Vein Study. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:921-931.

6. Howlader MH, Smith PD. Symptoms of chronic venous disease and association with systemic inflammatory markers. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:950-954.

7. Ruckley V, Evans CJ, Allan P, Lee AJ, Fowkes FG. Telangiectasia in the Edinburgh Vein Study: epidemiology and association with trunk varices and symptoms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:719-724.

8. Carpentier PH, Cornu-Thénard A, Uhl JF, Partsch H, Antignani PL, et al. Appraisal of the information content of the C classes of CEAP clinical classification of chronic venous disorders: a multicenter evaluation of 872 patients. J Vasc Surg. 2003,37: 827-833.

9. Carpentier PH, Maricq HR, Biro C, Ponçot-Makinen CO, Franco A. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical patterns of chronic venous disorders of lower limbs: a population-based study in France. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:650- 659.

10. Kahn SR, M’lan CE, Lamping DL, Kurz X, Bérard A, Abenhaim LA; VEINES Study Group. Relationship between clinical classification of chronic venous disease and patient-reported quality of life: results from an international cohort study. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:823- 828.

11. Langer RD, Ho E, Denenberg JO, Fronek A, Allison M, Criqui MH. Relationships between symptoms and venous disease: the San Diego population study. Arch Int Med. 2005;165:1420-1424.

12. Chiesa R, Marone EM, Limoni C, Volontè M, Petrini O. Chronic venous disorders: correlation between visible signs, symptoms, and presence of functional disease. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:322-330.

13. Rabe E, Guex JJ, Puskas A, Scuderi A, Fernandez Quesada F; VCP coordinators. Epidemiology of chronic venous disorders in geographically diverse populations: results from the Vein Consult Program. Int Angiol. 2012;31:105-115.

14. Nicolaides AN, Allegra C, Bergan J, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs: guidelines according to scientific evidence. Int Angiol. 2008;27:1-59

15. van Korlaar I, Vossen C, Rosendaal F, Cameron L, Bovill E, Kaptein A. Quality of life in venous disease. Thromb Haemost. 2003;90:27-35.

16. Smith JJ, Garratt AM, Guest M, Greenhalgh RM, Davies AH. Evaluating and improving healthrelated quality of life in patients with varicose veins. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:710-719.

17. Kurz X, Lamping DL, Kahn SR, et al. Do varicose veins affect quality of life? Results of an international populationbased study. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:641- 648.

18. Durkin MT, Turton EP, Wijesinghe LD, Scott DJ, Berridge DC. Long saphenous vein stripping and quality of life – a randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;21:545-549.

19. MacKenzie RK, Paisley A, Allan PL, Lee AJ, Ruckley CV, Bradbury AW. The effect of long saphenous vein stripping on quality of life. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:1197-1203.

20. Weiss RA, Weiss MA. Resolution of pain associated with varicose and telangiectatic leg veins after compression sclerotherapy. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:333-336.

21. Kaplan RM, Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Bergan J, Fronek A. Quality of life in patients with chronic venous disease: San Diego population study. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:1047-1053.

22. Perrin M. The impact on quality of life of symptoms related to chronic venous disorders. edicographia. 2006;28:146- 152.

23. Palfreyman SJ, Drewery-Carter K, Rigby K, Michaels JA, Tod AM. Varicose veins: a qualitative study to explore expectations and reasons for seeking treatment. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:332-340.

24. Darvall KA, Bate GR, Sam RC, Adam DJ, Silverman SH, Bradbury AW. Patients’ expectations before and satisfaction after ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy for varicose veins. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:642- 647.

25. Campbell WB, Decaluwe H, Macintyre JB, Thompson JF, Cowan AR. Most patients with varicose veins have fears or concerns about the future, in addition to their presenting symptoms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:332- 334

26. Lyseng-Williamson A, Perry CM. Micronised purified flavonoid fraction. A review of its use in chronic venous insufficiency, venous ulcers and haemorrhoids. Drugs. 2003;63:71-100.

27. Coleridge Smith PD. Drug treatment of varicose veins, venous edema, and ulcers. In: Gloviczki P, ed. Handbook of Venous Disorders: Guidelines of the American Venous Forum. 3rd ed. London, UK: Hodder Arnold; 2009: 359-365.

28. Veverkova L, Kalac J, Jedlicka V, et al. Analysis of surgical procedures on the vena saphena magna in the Czech Republic and an effect of Detralex during its stripping. Rozhl Chir. 2005;84:410-412.

29. Pokrovsky AV, Saveljev VS, Kirienko AI, et al. Surgical correction of varicose vein disease under micronized diosmin protection (results of the Russian multicenter controlled trial DEFANS). Angiol Sosud Khir. 2007;13:47-55.

30. Simsek M, Burak F, Taskin O. Effects of micronized purified flavonoid fraction on pelvic pain in women with laparoscopically diagnosed pelvic congestion syndrome: a randomized crossover trial. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2007;34:96-98.

31. Guyatt G, Gutterman D, Baumann MH, et al. Grading strength of recommendations and quality of evidence in clinical guidelines: report from an American College of Chest Physicians task force. Chest. 2006;129:174-181.

32. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924- 926.