The “C0s” patient: worldwide results from the Vein Consult Program

Eberhard RABE2,

Sanchez Ignacio ESCOTTO3,

José-Román ESCUDERO4,

Angelo SCUDERI5,

Hendro Sudjono YUWONO6,

and the Vein Consult Program coordinators7

2. Department of Dermatology, University of Bonn, Germany

3. National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico

4. Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain

5. Instituto Sorocabano de Pesquisa de Molestias Circulatorios (INSPEMOC), São Paulo, Brazil

6. Hasan Sadikin General Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia

7. National coordinators of the Vein Consult Program (VCP): Alberti T, Venezuela; Andercou A, Giurcaneanu C, and Puskas A, Romania; Dinh Thi Thu H and Le Nu Thi Hoa H, Vietnam; Escotto Sanchez I, Mexico; Escudero JR, Spain; Guex JJ, France; Hoyos AS, Colombia; Kazim Y and Swidan A, United Arab Emirates; Kecelj Leskovec N and Planinsek Rucigaj T, Slovenia; Larisa C, Ukraine; Liptak P, Slovakia; Matyas L, Hungary; Paocharoen V, Thailand; Pargalava N, Georgia; Radak D and Maksimovic Z, Serbia; Saveliev V, Russia; Scuderi A, Brazil; Yuwono HS, Indonesia

ABSTRACT

The Vein Consult Program is an international, observational, prospective survey that aims to collect global epidemiological data on chronic venous disorder (CVD)-related symptoms and signs based on the Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, and Pathophysiological (CEAP) classification, assess the impact CVD may have on an individual’s daily activities, and identify CVD management practices worldwide.

The survey was organized within the framework of ordinary consultations with general practitioners (GPs) trained in the use of the CEAP classification. Screening for CVD was performed by enrolling all consecutive outpatients over 18 years of age, whatever the reason for their consultation. Patients’ data were recorded and patients were classified according to the CEAP, from stage C0s to C6. GPs were able to refer screened patients with CVD to a venous specialist for further ultrasound investigation.

A total of 6232 GPs participated in the program and 91545 subjects were analysed, of whom 15290 (19.7%) were assigned to category C0s. The percentage of the global survey population eligible for a venous specialist consultation was 22.2%, but C0s subjects comprised only 4.1% (n=634). In the total survey population only 43% of eligible patients visited a specialist, but surprisingly most C0s patients eligible for referral did visit a specialist. Among the C0s patients a duplex scan investigation was performed in 14%. The majority were found to have reflux, which was mostly superficial, but an appreciable percentage (18%) had deep reflux.

C0s individuals were younger with a lower body mass index compared with the C1 to C6 subjects (48.6 versus 55.5 years; and 25.76 versus 27.24 kg/m2, respectively), and had fewer CVD risk factors.

Of all screened women, 18.5% were at the C0s stage versus 22.4% of screened men. Whatever the age group, men were more likely to be assigned to the C0s class of the CEAP than women, except in the 18-34 age bracket.

Although the quality of life of C0s subjects was impaired, they were often not considered to have CVD by GPs (25.5% in C0s versus 71% in the total surveypopulation), and were poorly treated (13% received lifestyle advice).

It is not known whether C0s subjects deserve more investigation and treatment as longitudinal studies providing information on the possible progression of disease in such patients are lacking. Nevertheless, given the inflammatory nature of CVD, we can speculate that treatments able to hamper inflammation would at least relieve C0s symptoms.

INTRODUCTION

The grading of chronic venous disorders (CVD) was simplified and standardized by the introduction of the Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, and Pathophysiological (CEAP) classification system.1 The CEAP classification categorizes limbs into seven classes from C0 to C6. Each clinical class is further characterized by a subscript (S) if the categorized limb is symptomatic, or a subscript (A) if the limb is asymptomatic. C0s patients are defined as those presenting with one or more CVD-related symptoms, but showing no clinical signs of the disease during a physical examination, and generally no abnormalities on a duplex scan. In a revised CEAP classification published in 2004, the C0s patient profile was introduced.2 Patients in this category are described as C0s,En,An,Pn as no etiology, anatomical localisation or pathological cause can be found. Symptoms associated with CVD and with the C0s stage were further defined as “complaints related to venous disease, which may include tingling, aching, burning, pain, muscle cramps, swelling, sensations of throbbing or heaviness, itching skin, restless legs, leg-tiredness and/or fatigue. Although not pathognomonic, these may be suggestive of chronic venous disease, particularly if they are exacerbated by heat or dependency in the day’s course, and relieved with leg rest and/or elevation.”3

Despite the acknowledgment that symptoms play an important part in CVD, little is known about their prevalence, particularly in the C0s patient. The aim of the present analysis was to determine the prevalence and clinical profile of C0s patients worldwide, how such patients are managed by general practitioners (GPs) in different geographical areas, the rate of spontaneous consultations due to C0s, and finally the impact of symptoms alone on patients’ quality of life. This was achieved through the Vein Consult Program (VCP), an international, observational, prospective survey carried out as an initiative of the Union Internationale de Phlébologie to raise awareness of CVD among patients, healthcare professionals, and health authorities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The VCP was conducted within the framework of ordinary GP consultations over a very short period of time (less than 2 weeks) to gather nationally representative data on the prevalence of CVD-related symptoms, signs, and CEAP classes. The design was a cross-sectional, two-part survey. In the first part of the survey, GPs recruited consecutive patients aged 18 years and over attending the practice for a routine consultation. Practices were distributed throughout the country and included both urban and rural locations. The only patients excluded were those attending for emergency visits. Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

The initial survey was conducted as a face-to-face interview. The 23-item questionnaire consisted of four sections and determined the individuals’ demographics; CVD risk factors; any patient-reported symptoms suggestive of CVD such as leg pain, heat sensation, and itching; and any visible signs of CVD. Signs, including telangiectasies, varicose veins, edema, trophic changes, and/or ulcers, were reported by patients themselves, and confirmed by the physician during a physical examination. Patients were then assigned to an appropriate clinical category (C) according to the CEAP classification when any type of venous pathology (classification C1–C6) was seen in at least one leg. The results were recorded by physicians in a case report form. The grade was determined by considering only the highest single reported sign. Physicians were requested to report whether patients complained about their legs spontaneously. All patients with a physician diagnosis of CVD were invited to complete a 14-question form of the ChronIc Venous Insufficiency Questionnaire (CIVIQ-14).4

Physicians could refer any individuals with a diagnosis of CVD to a venous specialist, using their normal procedure. The aim of the second part of the survey was to confirm the initial physician diagnosis of CVD. The specialists completed an additional questionnaire to establish the patient’s history of CVD and CVD risk factors. They also investigated the CVD status of thepatient using Doppler or duplex scanning and determined whether treatment was required. The specialists were unaware of the physicians’ initial diagnosis.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Unless otherwise specified, qualitative and quantitative variables were respectively described as number (percentage) and mean ± standard deviation. Percentages were calculated out of the total number of valid answers, excluding missing values. In case of missing values, the number of valid answers was presented. For cross tables, statistical tests were performed to compare means for quantitative variables using the Student t-test or analysis of variance for one factor, and frequencies for qualitative variables using the Chi² test. An α level of 0.001 was used, and a P-value equal to or lower than 0.001 indicated a statistically significant difference.

For the venous specialist questionnaire, the prevalence of CVD was estimated as the number of patients with a Doppler abnormality (primary CVD with or without other symptoms) out of the total number of patients who received a Doppler examination.

For CIVIQ-14 (ChronIc Venous Insufficiency Questionnaire with 14 questions), a global index score (GIS) was calculated with values ranging from 0 to 100. In this analysis, we adopted the following scoring convention: GIS 0 equals worst score and GIS 100 equals best score.

RESULTS

The VCP was conducted between October 2009 and July 2011 in five geographical zones: Western Europe (France and Spain; 36 004 subjects), Central and Eastern Europe (Georgia, Hungary, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Ukraine; 32 225 subjects), Latin America (Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela; 12 686 subjects), the Middle East (Pakistan, United Arab Emirates; 3518 subjects), and the Far East (Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam; 7112 subjects) totalling 20 countries.

Of the people who agreed to be screened, 91 545 had files suitable for analysis. The mean age of global participants was 50.6 ± 16.9 years, 68% were female, and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 26.17 ± 5.07. The profile of the global population of the survey has already been published elsewhere,5 and the distribution of patients among the CEAP clinical classes was as follows: 16 901 (21.7%) in C1, 13 888 (17.9%) in C2, and 18 863 (24.3%) in C3 to C6 (chronic venous insufficiency patients), totalizing 46 451 patients. The number of subjects complaining solely of symptoms, the so-called C0s patients, was 15 290 (19.7%), indicating that almost 20% of the survey population had CEAP grade C0s. Only 12 774 (16.4%) individuals had no symptoms or signs of CVD and thus were exempt from leg problems (C0a).

Clinical profile of the C0s patient and comparison with the surveyed population presenting with clinical signs (C1 to C6 of the CEAP)

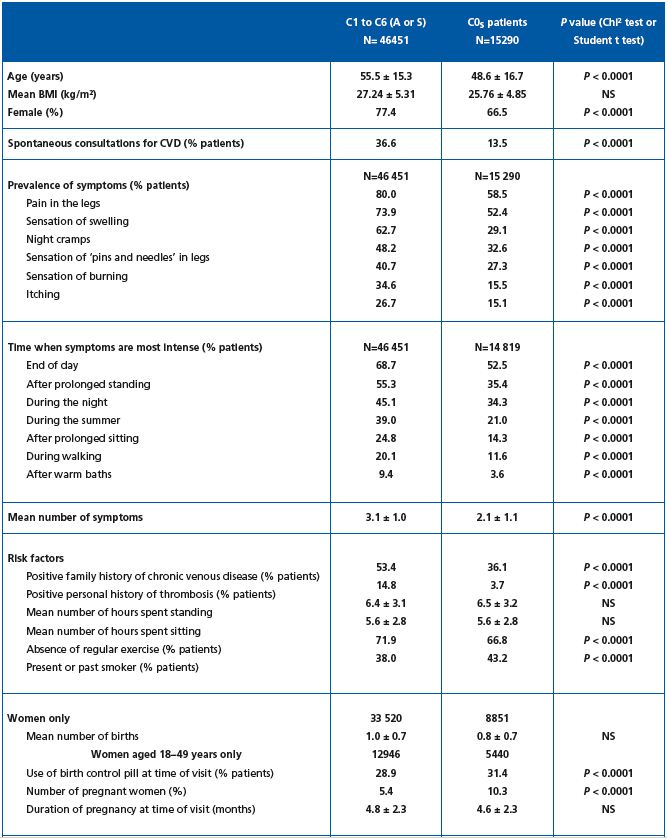

As shown in Table I, screened subjects were younger in the C0s than the C1 to C6 population: 48.3 ± 16.8 years versus 55.5 ± 15.3 years (P<0.0001), less often female (65.9% in C0s versus 77.4%; P<0.0001), with a lower BMI, although the latter did not reach statistical significance (25.76 ± 4.85 versus 27.24 ± 5.31; P=NS). Overall, the screened population was overweight (26.17 ± 5.07).

Frequency of CVD symptoms (Table I)

Participants described their symptoms in response to the questions set by the physician. The most frequent complaints in the C1-C6 population of the survey were ‘heavy legs,’ reported by 80%; ‘pain in the legs,’ reported by 74%; ‘sensation of swelling,’ reported by 63%, and ‘night cramps,’ reported by 48%. The average number of symptoms per patient was 3.1 ± 1.0. Symptom distribution and ranking was respected compared with the global population (not shown).5 In the C0s population, despite symptoms being reported less frequently, the symptom distribution and ranking were similar to those of symptomatic subjects in the C1 to C6 population of the survey, except that night cramps ranked higher. The mean number of reported symptoms was lower in the C0s population compared with the C1- C6 population (2.1 versus 3.1; P<0.0001). Subjects were also asked what exacerbated their symptoms. The most frequent response, reported by 68.7% of symptomatic C1 to C6 participants, was that their complaints ‘increase at the end of the day.’ Subjects in C1 to C6 classes also reported that their complaints: ‘increase with prolonged standing’ (55.3%), ‘increase during the night’ (45.1%), ‘increase in the summer’ (39.0%), ‘worsen duringprolonged sitting’ (24.8%), and ‘worsen during walking’ (20.1%).

Table I. Comparison of the clinical profile of the C0s subjects of the VCP survey with that of C1 to C6 patients, either asymptomatic (A) or

symptomatic (S).

Subjects in the C0s survey population reported significantly less often exacerbation of symptoms than the C1 to C6 population (Table I), but the ranking was identical, except for ‘during night’ and ‘after prolonged standing,’ which were reported by equal numbers of C0s subjects.

Risk factors

No significant difference in the mean BMI was found between the C0s and the C1 to C6 sub-groups of screened participants.

A family history of CVD was more often reported in C1 to C6 participants than in C0s subjects (53.4% versus 35.3%, respectively, P<0.0001). Similarly, C1 to C6 patients presented more frequently with a personal history of deep vein thrombosis compared with C0s subjects (15% versus 3.7% in C0s, P<0.0001), and were more likely to lack regular exercise (72% versus 67% in C0s; P<0.0001). On the other hand, C0s subjects were more frequently current or past smokers (43% in C0s versus 38% in C1-C6, P<0.0001). The average time spent standing and sitting was similar in both populations. The number of women on the birth control pill and the number of pregnant women were significantly higher in the C0s group.

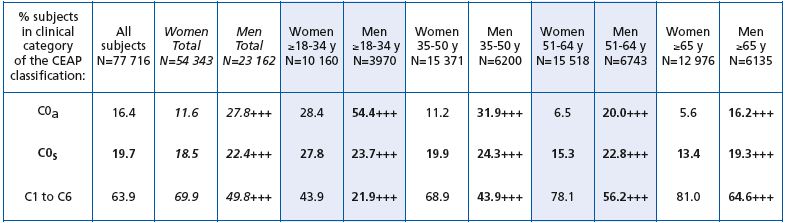

Men were more likely to be disease free (C0a) than women (27.8% of VCP men versus 11.6% of VCP women), whatever their age (P< 0.0001). Men were also more likely to be assigned to the C0s class compared with women (22.4% of VCP men versus 18.5% of VCP women). This was true for all age groups with the exception of the ≤18 to 34-year age bracket. In this group, a significantly greater percentage of women than men were assigned to the C0s class, as most of the latter had no venous problems (54.4% of men aged ≤18 to 34 years were in C0a versus 28.4% of women of the same age). In terms of CVD signs, women were more often assigned to CEAP classes C1 to C6 than men whatever their age (69.9% women versus 49.8% men; P< 0.0001).

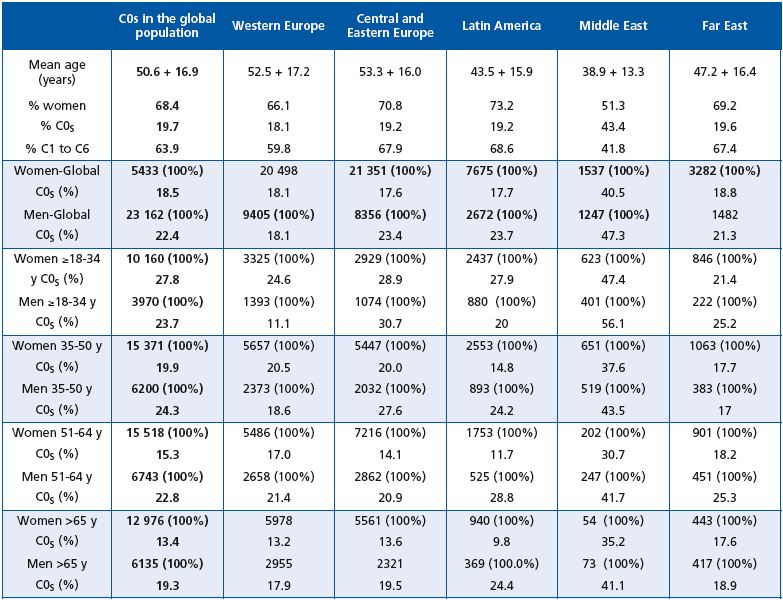

As reported above, men less than 34 years of age were less frequently encountered in C0s than women of the same age. This was true for Western Europe and Latin America only. After the age of 34 years, men assigned to the C0s class were more numerous than women whatever the geographical area, except in Western Europe and the Far East where the percentage of women in C0s was slightly higher than that of men in the 35-50-year age bracket.

The Middle East had the highest percentage of women and men in C0s whatever the age. In this geographical region, the ratio of women to men was almost equal, but men were more likely to consult than women after the age of 50 years. In general, however, women were far more likely to consult than men whatever the geographical region or age bracket.

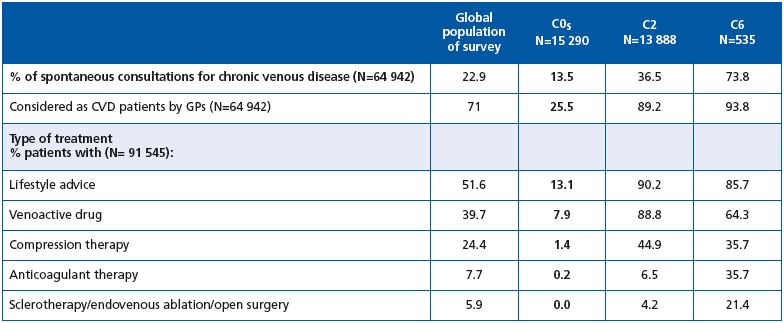

Spontaneous consultations for venous problems were less frequent among C0s subjects compared with the C1- C6 population (13.5% versus 36.6%, respectively, P=0.0001, Table I), and with the global population of the survey (13.5% versus 22.9%, respectively, Table IV). The frequency of spontaneous consultation increased with CEAP class (36.5% of C2 and 73.8% of C6 subjects consulted spontaneously for venous leg problems).

Table II. C0s profile of screened subjects by age and gender.

P difference between men and women: +++, P<0.0001

Table III. C0s profile of the screened subjects by age, gender, and geographical area.

Table IV. Treatment of C0s subjects in the Vein Consult Program. Comparison with the global population of the survey and with C2 and

C6 patients.

GPs considered 71% of the total survey population to have CVD. Of the 15 290 patients in C0s, only 3902 (25.5%), ie, one-quarter were considered to have CVD by GPs, which is far less than in the global survey population. In the C2 class, 89.2% were considered to have CVD by GPs, and in C6, 93.8% were considered to have CVD.

The percentage of C0s patients considered to have CVD was highest in Western Europe (almost 38%) and the Far East (56%). In contrast, C2 patients were less likely to be considered as having CVD in these two regions. Patients with ulcers were under-recognized in the Far East (69.8% were considered to have CVD by GPs, versus 93.8% for the global survey population).

C0s patients were poorly treated in general: only 13% received lifestyle advice and 8% were prescribed a venoactive drug. In contrast, lifestyle advice and drugs were administered to the majority of patients in the global population as well as those in C2 and C6. It is noteworthy that venoactive drugs were prescribed twice as frequently as compression therapy for C2 and C6 stages.

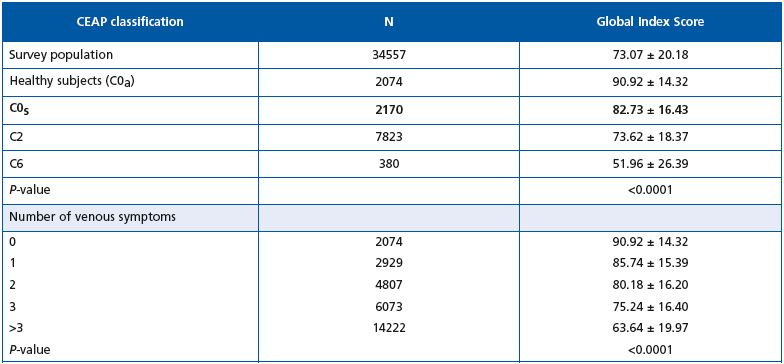

The GIS for the total survey population was 73.07. The GIS of C0s patients was lower (82.73) than that of healthy subjects (90.92), indicating that their quality of life was slightly worse. Quality of life decreased with increasing CEAP class (73.62 in C2 and 51.96 in C6), and drastically worsened with the mean number of presenting symptoms.

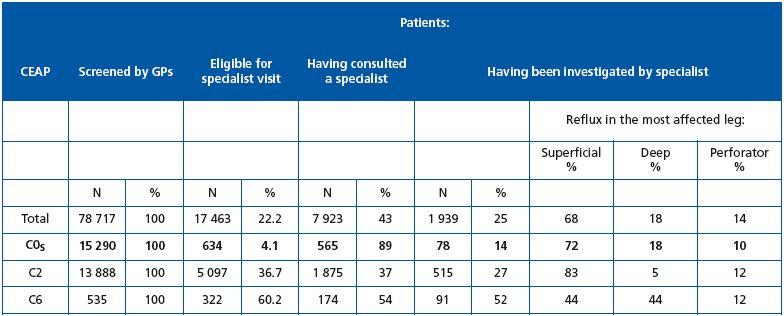

GPs referred 22.2% of the global population to venous specialists. This included only 4.1% of C0s patients, 36.7% of C2 patients and 60.2% of C6 patients. It is interesting to note that a relatively low proportion of C2 and C6 patients eligible for referral actually visited a venous specialist (37% and 54%, respectively) compared with 89% of C0s patients.

Among the 565 C0s patients who visited a specialist, only 78 right legs and 69 left legs were investigated with either Doppler (45.4%) or duplex scan (54.6%). Most C0s legs had superficial reflux (72% and 67% in the right and left legs, respectively), 11% had perforator reflux, but an appreciable percentage had deep reflux (18% and 20% in the right and left legs, respectively). This suggests that the C0s patients referred to a specialist were suspected of having a thrombotic problem that was detected by clinical examination at the GP level. It is noteworthy that 27% of C2 and 52% of C6 patients underwent investigation.

Table V. Quality of life score according to the CEAP profile and the number of venous symptoms.

Table VI. Patient referral to venous specialists and characteristics of reflux in subjects referred to venous specialists. Comparison between

C0s, C2 and C6 patients.

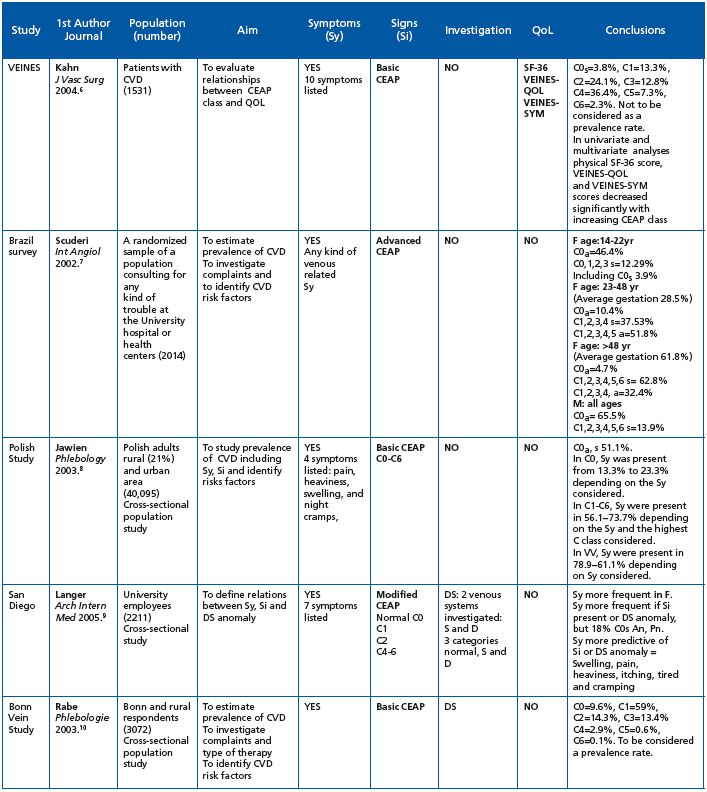

DISCUSSION

The VCP is one of the few surveys to have specifically screened for C0s subjects, which the CEAP identifies as patients with symptoms, but without visible clinical signs of CVD. However, despite the fact that the C0s profile is globally recognized, prevalence data on this category remain scarce. Although some studies have reported CVD symptoms (Table VII), prevalence data for the C0s class are usually missing. Results of previous surveys have allowed indirect calculations of C0s prevalence to be made: 3.8% in the VEINES study,6 3.9% in the Brazilian survey,7 13%-23 % in the Polish study,8 and 15% in the San Diego Vein Study.9 C0s prevalence was not reported in the Bonn Vein study.10 In the present survey, almost 20% of individuals could be classified as C0s,5 which represents a significant proportion of the population. Interestingly, these C0s patients were equally distributed throughout the geographical zones, with the exception of the Middle East where the percentage of C0s patients was far higher (47.3% of men and 40.5 % of women). The young age of the screened patients together with the warm climate in this part of the world might be an explanation for such high numbers. The profile of the C0s patient could be distinguished from that of the global VCP population in that women were proportionally less represented, subjects were younger, with a lower BMI and fewer CVD risk factors. Symptoms in C0s subjects were evenly distributed compared with the global population, but had the same ranking; heaviness, pain and sensation of swelling being the most commonly encountered symptoms. The frequency of each symptom was lower in C0s subjects compared with individuals in the global survey population due to their younger age; the VCP has shown that the presence of CVD symptoms increases with age.5 This is in line with former surveys.10

The frequency of a C0s classification was higher in men than women, with the exception of men aged 18-34 years who in general did not even have CVD symptoms. This would suggest that symptoms appear later in men than women. Fiebig reported a different timing of disease in the two sexes and concluded that women experienced an earlier disease onset, with the first symptoms of CVD observed at a mean of 30.8 years of age, compared with 36.8 years in men.11 In the VCP survey, the Middle East was characterized by a particularly high level of C0s in both men and women compared with other regions, and by a higher percentage of men consulting for CVD. It is not known if this is due to cultural or social differences.

Table VII. Review of the literature on epidemiological studies that have used the CEAP classification and have assessed symptoms.

Abbreviations: CIVIQ = chronic venous insufficiency questionnaire; CVD = chronic venous disorder; CVI = chronic venous insufficiency (defined as chronic changes in the skin and subcutaneous tissues [C3 to C6]); C2 trunk = VV of the GSV and SSV trunks or their first or second generation branches; D = deep venous system; DS = duplex scanning; F = female gender; LL = left lower limb; M = male gender; N = number; QOL = quality of life; RL = right lower limb; RV = reticular vein; S = superficial venous system; S-F 36 = generic short-form health survey questionnaire; Si = signs; Sy = symptoms; T = telangiectasia; VV = varicose vein; VEINES-QOL = venous-disease specific questionnaire; VEINES-SYM = venous symptom severity questionnaire.

The present analysis showed a relationship between impaired quality of life and increasing CEAP class, as well as with increasing number of symptoms, a finding that has also been demonstrated in other studies.6,12 Although they may be experiencing a poorer quality of life, C0s patients were hesitant to consult GPs, and even when they did so they received little treatment. Furthermore, only 13% received any lifestyle advice. It is important to note the lower-than-expected prescription of compression therapy in this survey, even at severe CVD stages, highlighting the need for patient and GP education.

The results of this survey suggest that C0s subjects are very frequently encountered in general practice, particularly in Western Europe and the Far East, the two regions where individuals were also more likely to be considered as to be suffering from CVD. However, only 4% of C0s subjects were referred to a specialist (referral was almost nonexistent in the Far East, and it is noteworthy that an appreciable proportion of C0s individuals who did consult a venous specialist were suffering with secondary venous disease.

The present analysis provides a snapshot of C0s subjects in ordinary consultation. A limitation is that this was not a longitudinal study and therefore the future of these C0s individuals and their CVD progression is not known. It remains to be determined whether such individuals deserve more in-depth investigation and care because of the possible progression of their symptoms to more severe stages of CVD. In the San Diego Vein Study, up to 15.5% subjects complaining of leg ache had no functional anomaly, and up to 14.2% of subjects with pain had no visible signs of CVD.9 As a result, leg pain was considered a non-specific CVD symptom by the authors of this study, in which case the C0s subject would be denied a diagnosis of CVD.

Our understanding of the mechanisms at work in CVD related pain is gaining momentum. A considerable body of evidence now shows that inflammatory reactions via the release of various mediators are involved in disease progression and might explain the origins of venous pain. Nerve structures known as C-nociceptors that are easily activated by inflammatory mediators have been found in the media of varicose veins13 and are also located in perivenous connective tissue.14 Such nociceptors are thought to be activated in the microcirculation, where contact between nerve endings, the arteriole, the vein, and the capillary is probably much closer than at a macrovascular level. Microcirculatory parameters have been studied and vary with increasing severity of CVD.15,16 We are presently just able to assess macrocirculatory parameters, but these are not usually abnormal at the C0s stage, and there are currently no instrument sensitive enough at our disposal to assess the microcirculation at stages as early as C0s. Without a means of assessment, we can only speculate that venous pain at the C0s stage might be the result of a disturbed microcirculation, but this remains to be documented.

Early work by Andreozzi brought attention to C0s subjects, who he referred to as hypotonic phlebopathic patients because of normal Duplex investigations, but disturbed parameters with photo- and strain-gauge plethysmography, leading him to suggest a hyperdistensibilty of the venous wall.17 More recently, a study of casts from amputated legs has revealed that valvular incompetence can exist in the microvalves out to the third generation ‘boundary’of tributaries from the great saphenous vein (GSV) from stages C0 and C1, even though no truncular reflux could be observed in the GSV.18 Such findings lend support to a role for early degenerative processes in the microvasculature, long before the macrocirculation is targeted.

CONCLUSION

Little is known about the future of subjects with C0s, a group that has until recently been poorly studied, but an inflammatory hypothesis to explain the nature of the reported symptoms is plausible. Given the high prevalence of such subjects in the population, whatever the geographical region, it would be beneficial to know which C0s patients deserve investigation and treatment. In the meantime, treatment that could delay and even hamper the inflammatory progression of the disease might prove useful. It has been shown that the symptoms of C0s individuals are greatly improved with conservative treatments, in particular, by venoactive drugs such as micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF at a dose of 500 mg*).19

*Also registered as: Alvenor®, Ardium®, Arvenum® 500, Capiven®, Detralex®, Elatec®, Flebotropin®, Variton®, Venitol®.

REFERENCES

1. Beebe HG, Bergan JJ, Bergqvist D, et al. Classification and grading of chronic venous disease in the lower limbs. A consensus state ment. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;12:487-491.

2. Eklof B, Rutherford RB, Bergan JJ, and the American Venous Forum International Ad Hoc Committee for Revision of the CEAP Classification. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:1248- 1252.

3. Eklof B, Perrin M, Delis K, Gloviczki P; American Venous Forum; European Venous Forum; International Union of Phlebology; American College of Phlebology; International Union of Angiology. Updated terminology of chronic venous disorders: the Vein Term Transatlantic Interdisciplinary Consensus Document. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:498-501.

4. Launois R, Lemoine JG, Lozano FS, Mansilha A. Construction and international validation of CIVIQ-14 (a short form of CIVIQ-20), a new questionnaire with a stable factorial structure. Qual of Life Res. 2011;21:1051-1058.

5. Rabe E, Guex JJ, Puskas A, Scuderi A, Fernandez Quesada F; VCP Coordinators. Epidemiology of chronic venous disorders in geographically diverse populations: results from the Vein Consult Program. Int Angiol. 2012;3:105-115.

6. Kahn SR, M’lan CE, Lamping DL, Kurz X, Bérard A, Abenhaim LA; VEINES Study Group. Relationship between clinical classification of chronic venous disease and patient-reported quality of life: results from an international cohort study. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:823- 828.

7. Scuderi A, Raskin B, Assal FA, et al. The incidence of venous disease in Brazil based on the CEAP classification. Int Angiol. 2002;21:316-321.

8. Jawien A, Grzela T, Ochwat A. Prevalence of chronic venous insufficiency in men and women: cross-sectional study in 40 095 patients. Phlebology. 2003;18:110-122.

9. Langer RD, Ho E, Denenberg JO, Fronek A, Allison M, Criqui MH. Relationship between symptoms and venous disease. The San Diego population study. Arch Int Med. 2005;165:1420-1424.

10. Rabe E, Pannier-Fischer F, Bromen K, et al. Bonner Ve nenstudie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Phlebologie. Phlebologie. 2003; 32:1-14. [German]

11. Fiebig A, Krusche P, Wolf A, et al. Heritability of chronic venous disease. Hum Genet. 2010;127:669-674.

12. Jantet G and the RELIEF Study Group. Chronic venous insufficiency: worldwide results of the RELIEF study. Reflux assEssment and quaLity of lIfe improvEment with micronized Flavonoids. Angiology. 2002;53:245- 256.

13. Vital A, Carles D, Serise JM, Boisseau MR. Evidence for unmyelinated C fibers and inflammatory cells in human varicose saphenous veins. Int J Angiol. 2010;19:e73-e77.

14. Danziger N. [Pathophysiology of pain in venous disease]. J Mal Vasc. 2007;32:1-7. Review. French.

15. Howlader MH, Smith PD. Correlation of severity of chronic venous disease with capillary morphology assessed by capillary microscopy. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:563-569.

16. Virgini-Magalhaes CE, Porto CL, Fernandes FF, Dorigo DM, Bottino DA, Bouskela E. Use of microcirculatory parameters to evaluate chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:1037-1044.

17. Andreozzi GM, Signorelli S, Di Pino L, et al. Varicose symptoms without varicose veins: the hypotonic phlebopathy, epidemiology and pathophysiology. The Acireale project. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2000;48:277-285.

18. Vincent JR, Jones GT, Hill GB, van Rij AM. Failure of microvenous valves in small superficial veins is a key to the skin changes of venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(6)suppl:62S-69S.

19. Perrin M, Ramelet AA. Pharmacological treatment of primary chronic venous disease: rationale, results and unanswered questions. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41:117-125.