Review of proceedings

A Call to Action: Reducing Venous Ulcers by Fifty Percent in 10 Years.

Proceedings of the Pacific Vascular Symposium 6. Kona, Hawaii,

November 12-15, 2009. Supplement S J Vasc Surg 2010; 52:1S-2S

In November 2009, a meeting at Big Island (HI), USA was attended by 60 invited international experts on venous disease, wound care, internal medicine, nursing, vascular technology, epidemiology, health care management, insurance industry, public policies, marketing, industry research and development, and government relationships. Most participants were US citizens, but experts from other countries were also present. The aim of the meeting was not to provide an update on venous ulcer (VUs), but the experts used the latest results in making their recommendations for reducing the prevalence of VUs by 50% over the next 10 years. To achieve this aim, the participants were divided into 4 working groups:

Group I: Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and postthrombotic disease (PTD).* Leaders: P. Henke and T. Wakefield

Group II: Primary chronic venous disease Leaders: P. Neglen and B. Eklof

Group III: Ulcer healing and recurrence prevention Leaders: D. Gillespie and B. Kistner

Group IV: Nonmedical issues Leaders: M. Passman and S. Elias

Their task was to list the critical issues to be addressed, which afterwards were presented and discussed in the plenary session chaired by A. Comerota. The four groups then worked separately to prioritize the critical issues and actions required, landmark measures and the timeline. Their proposals were again discussed in depth at a plenary session.

* Postthrombotic disease. In English and American English the te rm most commonly used is postthrombotic syndrome, but in this document both postthrombotic syndrome and disease are used. It is generally admitted that disease is the appropriate term for describing clinical features, ie, symptoms and signs related to a single known etiology, which is the case when dealing with sequelae of DVT. Conversely, syndrome applies to symptoms and signs that may be related to various etiologies. Confusion between disease and syndrome is attributed to Copland when he translated Galen’s works in 1541.

The leaders of each group then summarized their conclusions, and this document was reviewed various times by the group members before submission to the Journal of Vascular Surgery, knowing that P. Henke was editor.

The Journal of Vascular Surgery supplement is divided into seven parts. The first two describe in detail why this topic was chosen as well as the symposium’s goal, while the next four describe recommendations and actions for reducing the prevalence of VU. The last one is devoted to the presentation of 13 selected abstracts.

A – VENOUS ULCER DIAGNOSIS, TREATMENT,

AND PREVENTION OF RECURRENCE (GROUP III)

1. Recommendation and actions regarding the diagnosis of VU. An educational program should be developed to help primary care physicians classify leg ulcer as venous, nonvenous, or of mixed etiology. Public awareness is also needed to convince people to consult their general practitioner.

2. Recommendation and actions regarding VU treatment. Definitive care of VU can be divided into two parts: ulcer healing and recurrence prevention.

2-1. VU healing. Compression is the key factor. Nevertheless, there is no consensus regarding multilayer bandages or stockings, knowing that the main problem with compression remains compliance. Evidence-based studies are not available to show whether corrective operative procedures should be done while the ulcer is active or healed.

2-2. Recurrence prevention. Compression, correction of the underlying venous disease and surveillance are the three key actions. To fulfill these actions the medical profession and the public alike need to be educated.

2-2-1. Effective compression must be maintained on the extremity as long as the underlying cause of VU remains uncorrected and as long as swelling persists.

2-2-2. Correct axial superficial reflux and other readily correctable sources of reflux obstruction in all cases at during treatment of the first VU.

2-2-3. Develop guidelines for ongoing surveillance of patients presenting an ulcer.

B – PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF VENOUS

ULCERS IN PRIMARY CHRONIC VENOUS

INSUFFICIENCY (GROUP II)

Four critical issues were identified.

1. Standardization of diagnostic testing, especially ultrasound scanning for chronic venous disease and criteria for interpretation of the results. There are no known hemodynamic methods to identify which patients with primary chronic venous disease and limbs with C-class 2 to 4 will develop VU. To achieve this goal, other hemodynamic tests in addition to ultrasound scanning should be developed. Finally, it is possible to develop a practical protocol for chronic venous disease investigations for clinical practice and then to introduce a more sophisticated protocol for longitudinal research into chronic venous disease

2. Identification of factors (other than hemodynamic) to identify patients with primary chronic venous disease C-class 2-4 limbs who are at risk of progression to active leg ulcer. This approach was particularly innovative and the possible risk factors were listed. Some of them—age, “feeling of swelling”, hypertension, obesity, pregnancy, smoking, use of hormones—are known as varicose vein risk factors, but they need to be correlated with progression of the disease. Mechanical dysfunction of the calf muscle pump may enhance the development of VU. It may be of value to identify genetic factors, biomarkers of venous endothelium dysfunction, imbalance of humoral mediators of vasoconstriction and venous dilatation, differences in skin type/metabolism/race.

3. Identification of treatment that may prevent progression in patients with C2-C4 limbs to VU (C6). There is no study on the efficacy of compression therapy, venoactive drugs, or endovenous (thermal chemical ablation, stenting)/open surgery in preventing chronic venous disease progression. Such studies may be difficult to perform adequately, since it will be hard not to intervene in symptomatic patients with clinical classes below C6.

4. Calculation of the number of C2-C4 patients needed to treat to prevent VU. Based on C4-C6 the outcome of critical issues 1-3, it may be possible to acquire the information needed to perform a cost-benefit analysis.

C – PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF

POSTTHROMBOTIC SYNDROME (GROUP I).

Six topics were identified.

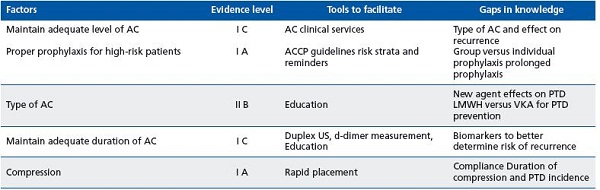

1. Prevention of DVT recurrence. Knowing that recurrent ipsilateral DVT is probably the most important factor in the development of PTD, practical measures to prevent recurrence are crucial. They include the best practices in the American College of Chest Physicians guidelines, which are presented in Table I. To promote use of guidelines it is recommended to provide the patient with a DVT information card to be given to their physicians, and to package it with compression stockings.

2. Compression/ambulation compliance. The benefits of elastic compression stockings after acute DVT have been well described in randomized controlled trials in the prevention of PTD. Additionally, when elastic compression stockings are combined with early ambulation, rates of PTD are decreased. Nevertheless, some ambiguity persists concerning the effectiveness of elastic compression stockings. First, it is unknown how long elastic compression stockings need to be worn to provide the prescribed amount of compression before they wear out. Second, it is not known whether elastic compression stockings are effective in patients with symptomatic distal DVT. Third, the compression strength (high or low) that prevents VU is not clearly established, given that lighter stockings are easier to apply than heavier ones (compression strength of 30 to 40 mm Hg). Fourth, it is unknown how long elastic compression stockings need to be worn.

Various actions may be recommended. The most applicable worldwide is to ensure that patients treated in emergency rooms as well as in an ambulatory setting wear appropriate stockings in addition to taking their anticoagulants. Further studies could be directed to the use of dynamic pulse compression as adjunctive therapy, and in developing microchips embedded in stockings for the measurement of pressure and compliance.

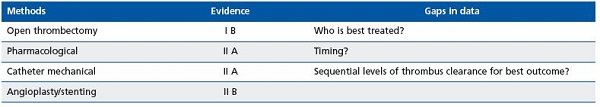

3. Early thrombus removal in patients with iliofemoral DVT. Thrombus removal with catheter-based procedures is likely an important component to reduction of PTD in DVT involving the iliocaval segment, although is not a strong recommendation in the American College of Chest Physicians 2008 guidelines. One practical measure to achieve this objective is to ensure early referral of patients with iliofemoral and extensive thrombosis to venous specialists. It is worth noting that the present classification of DVT as proximal and distal is not satisfactory and it seems appropriate to promulgate a more precise anatomical classification. Other points to be clarified are shown in Table II.

Abbreviations: AC anticoagulation; ACPP American College of Chest Physicians; LMWH low-molecular-weight heparin; PTD postthrombotic disease; US ultrasound; VKA vitamin K antagonist.

4. Elimination of postthrombotic iliofemoral venous obstruction. Chronic obstruction of the iliofemoral segment, independent of reflux, is the principal cause of PTD in approximately one-third of postthrombotic cases. This pathophysiological component is underdiagnosed, as various imaging techniques (ascending venogram, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance venography) do not provide reliable information on the degree of compression or on the hemodynamic significance of such lesions, given that the contribution of vein wall stiffness is unknown. Intravenous ultrasound scanning seems more reliable, but is invasive. Ballooning and stenting procedures that are presently the first-line operative treatment need to be evaluated using a dedicated registry so that best practice recommendations can be made.

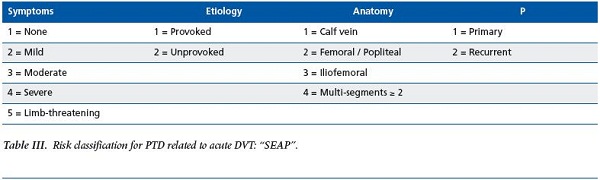

5. Stratification of patients with acute DVT who are at risk of developing severe PTD.

Although it is not possible to foresee the development and course of PTD in the individual patient, some clinical predictors of PTD are identifiable at the time of acute DVT. DVT involving the iliac and common femoral veins, elevated body mass index, previous ipsilateral DVT, older age, and inadequate anticoagulation have been associated with the development of PTD. Furthermore, patients who show symptoms of PTD one month after acute DVT have been found to develop PTD at 2 years. A DVT PTD risk prediction score including symptoms, etiology, and anatomy components has been proposed but needs to be validated (Table III). Also needed is a review of the PTD literature with regards to factors that predict ulcer progression, so as to define better the variables associated with PTD development and severity.

6. Pharmacological management of PTD. Venoactive drugs such as micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) and horse chestnut seed extract (HCSE) are used worldwide, except in the USA, as adjuvant therapy in the management of chronic venous insufficiency and VU. The peerreviewed literature contains a large body of evidence on the effectiveness of such venoactive drugs. As the PV6 group was set up by members of the majority AFV (see remark at the end of the review), they recommended conducting randomized controlled trials in an American population to support legal acceptance by their governing bodies.

Nevertheless some grade recommendations as mentioned in Table I and II should be debated.

D – NONMEDICAL INITIATIVES TO DECREASE VENOUS ULCER PREVALENCE (GROUP IV)

The goal of this group was to identify and prioritize critical issues and how to address them. Some of the group’s actions and recommendations are applicable only in the USA, others worldwide, and we will focus on the latter.

1. Lack of awareness of VU recognition, diagnosis, and prevention at all levels of the health care system. Recommendations: Develop educational programs targeting all levels of the care system, especially at the patient and primary care levels.

2. Variable quality of care for VU because of the poor coordination of care within all levels of the health care systems and lack of standard guideline implementation and compliance. Recommendations: There are too many guidelines from different sources, and a unified evidence base is critical in facilitating guideline implementation. Evidence-based guidelines need to address all levels of health services.

3. Poorly substantiated economics of prevention and treatment of VU leading to problems in determining cost-effective quality care and optimal reimbursement. High-quality data assessing the total economic burden of VU are lacking. Recommendations: Gather unbiased economic data by justifying health services and other health care payers of the value equation involved in VU prevention and quality care.

4. Funding for research in VU prevention and treatment is currently limited and studies on comparative effectiveness are lacking. Funding opportunities from national institutes of health for VU prevention and treatment have been limited in the past, with ongoing clinical trials funded mostly by other organizations. Recommendations: Develop a strong centralized foundation to promote research and education through national institutes of health, industry, and other alternative sources for studies of the comparative effectiveness of VU prevention and treatment.

5. Improving the care of VU requires development of governmental relationships and advocacy in order to provide input into health care policies addressing venous ulcer prevention and treatment goals.

6. Need for a strong central organization to promote all necessary elements requiered for prevention and treatment of VU. Recommendations for issues 5 and 6 mainly involved the AVF and consequently will not be described in this review (see remark at the end).

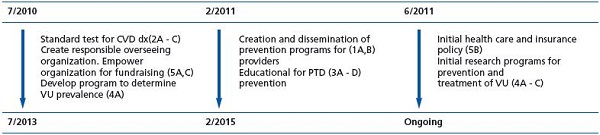

The 5th part of this J Vasc Surg supplement summarizes the major proposals (Figure 1) including a projected timeline for the overarching goal of VU reduction.

In the last part, 13 selected extended abstracts are presented.

1. O Nelzen, Uppsala, Sweden. Fifty percent reduction in venous ulcer prevalence is achievable – Swedish experience.

2. GL Moneta, Portland, Ore USA. Decreasing venous ulcers by 50% in 10 years: five critical issues in the diagnosis and investigations of venous disease.

3. JD Raffetto, Boston, Mass USA. The definition of the venous ulcer.

4. AH Davis, et al, London, UK. Natural history and progression of primary chronic venous disorder.

5. M Perrin, Lyon, France. Management of primary venous disorders in C6 patients.

6. W Marston, Chapel Hill, NC USA. Summary of evidence of effectiveness of primary chronic venous disease treatment.

7. S Vedantham, St Louis, Mo USA. Definition of postthrombotic disease.

8. SR Kahn, Montreal, Canada. Natural history of postthrombotic disease: transition from acute tochronic disease.

9. JA Caprini, Chicago, Ill USA. Critical issues in deep vein thrombosis prevention.

10. MH Meissner, Seattle, Wash USA. The effectiveness of deep vein thrombosis prevention.

11. S Raju, Flowood, Miss USA. Critical issues in ulcer prevention in postthrombotic disease.

12. RB McLafferty, Springfield, Ill USA. Evidence of prevention and treatment of postthrombotic syndrome.

13. P Pappas. Newark, NJ USA. Critical issues in prevention of postthrombotic re-ulceration. To support the recommendations, 564 references are listed.

I am grateful to A. Comerota B. Eklöf, RL. Kistner,F. Lurie, and T. Wakefield that accepted to amend the manuscript and honored with their final comment:” We have reviewed this synopsis of the detailed Journal of Vascular Surgery report with care and believe it clearly and succinctly reflects the content of the PVS-6 meeting. Dr. Perrin’s effort to promulgate this conference’s intent to improve the care of the venous ulcer patient and ultimately to decrease the incidence of its occurrence is greatly appreciated.”

NB. It should be borne in mind that the most active members of the American Venous Forum initiated the meeting. Consequently, some recommendations and actions are specific to the USA, and not applicable to other countries, and so will not be developed.

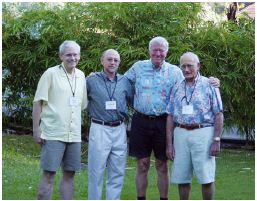

From left to right Thomas Wakefield, Fedor Lurie,

Bo Eklöf, Robert Kistner.