CLINICAL CASE 4. Chronic occlusion of inferior vena cava and pelvic venous disease

Kirill Lobastov, MD, PhD

Pirogov Russian National Research

Medical University, Moscow, Russia

Anastasia Akulova, MD, PhD

Central Clinical Hospital “Railway-Medicine,” Moscow, Russia

A woman, 29 years old, asked for medical attention in 2021 due to complaints of heaviness in the lower limbs, varicose veins on the left thigh, and painful menstruation. As known from her personal history, at the age of 7 months, she sustained an extensive skin burn that required skin grafting. After that, she had no complaints till 2016, when, at 24 years old, she initially noted varicose veins on the left lower limb. In 2018, at 26 years old, she underwent high ligation and stripping of the great saphenous vein (GSV) on the left side. In 2021, she noted varicose veins recurrence on the same limb and the appearance of painful menstruation that forced her to seek medical attention. She had no pregnancies and never used contraceptive pills.

Clinical examination revealed no changes in limb size, normal skin color without trophic changes, the presence of a 4-cm scar in the inguinal region on the left side, and minor spots after stab incisions on the left thigh and calf. Varicose veins without any pain and inflammation were observed on the medial aspect of the left thigh and calf and the left side of the abdominal wall. No changes were found on the right lower limb (Figures 1 and 2).

A duplex ultrasound showed the absence of GSV trunk or its stump on the left thigh and a trunk with neither reflux nor dilation on the calf. The varicose veins of the limb and abdominal wall were connected with perineal veins of 2 to 4 mm in diameter that represented reflux with the Valsalva maneuver and with distal compression.

Due to painful menstruation and signs of pelvis-perineal reflux, a transvaginal ultrasound scan was performed. It revealed no pathological changes in the uterus and ovaries, whereas parametrial veins were dilated up to 13 to 15 mm with spontaneous blood contrasting. Reflux in parametrial veins was detected with the Valsalva maneuver.

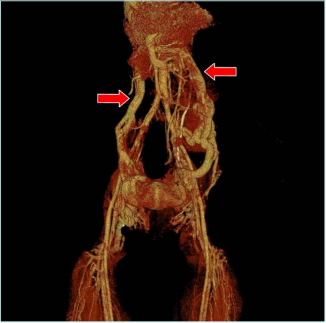

The patient was referred to computed tomography (CT) venography. It found postthrombotic changes in the infrarenal, renal segment of the inferior vena cava (IVC); on the right side, common iliac vein (CIV), external iliac vein (EIV), common femoral vein (CFV) and femoral veins; and on the left side, CIV, EIV, and femoral vein. The gonadal veins (GV) were dilated up to 14 mm on the right and 19 mm on the left side. Also, anastomosis of the left GV with ascending lumbar veins was detected. The obturator veins were dilated up to 7 mm on the right and 4 mm on the left. There were observed dilated ascending lumbar veins with uneven contours, the presence of retractions, and postthrombotic intraluminal contrast defects with drainage into the system of unpaired and semi-unpaired veins (Figures 3 and.4). Thus, CT venography concluded the postthrombotic obstruction of IVC and iliac veins on both sides with collateral blood flow through dilated right and left GV, lumbar veins, and obturator veins.

The final diagnosis is C2rs Esi As,d Pr (NSV, PELV) Po (IVC, CIV, IIV, EIV, CFV) LIII by CEAP (clinical, etiological, anatomical, pathophysiological) 2020 classification, and S2 V2,3b Po (IVC, BCIV, BEIV) Pr (BGV, PELV) by SVP (symptoms-varices pathophysiology) classification.1,2

Discussion

Dr Geroulakos. The clinical stage of the patient’s recurrent venous disease is C2, and she only complains of painful menstruation. In addition, the degree of stenosis in the inferior vena cava (IVC) is not known. It is highly unlikely that symptoms will change with IVC stenting, and painful menstruation is not a recognized indication for iliocaval stenting.

Dr Josnin. My opinion for this patient would be to initially implement an optimized medical treatment, including prevention of new thrombosis, optimization of venous compression, and venoactive drug treatment. Endovenous treatment would be re-evaluated in case of ineffectiveness of these measures, taking into account the non-negligible risk of failure of the procedure and/or postprocedure recurrence and, of course, the patient’s current complaints.

Dr Kan. Patients with IVC obstruction may have chronic lower-limb venous disease symptoms, experience acute deep venous thrombosis (DVT), or be restricted from physical activity.3 Conservative treatment with anticoagulation and compression therapy may provide symptomatic relief and prevent recurrent thrombosis, but a number of patients will progress. The endovascular approach with stent placement for chronic IVC obstruction is a safe treatment option to help patients without limited clinical improvement. For some problematic cases, surgical reconstruction of the IVC has been described in publications by surgical bypass.4

Figure 3. Computed tomography (CT) venography. Red

arrows mark obstruction of infrarenal interior vena cava.

Figure 4. Computed tomography (CT) venography with

3-dimensional reconstruction. Red arrows mark dilated left

and right gonadal veins.

However, if we do not do endovascular procedures for these patients, there is no hope of sustained clinical improvement and possible symptom relief. According to the patient’s current condition, even though the patient currently has symptoms of dysmenorrhea and a recurrence of varicose veins, there are no changes in limb size, and she has normal skin color without trophic changes. We could try to wire and connect the long-occluded iliac vein to the IVC, but this might be challenging. But we also can choose conservative treatment first because the symptom now seems to have no strong indication for IVC stenting.

Dr Nikolov. If asymptomatic (no leg edema, no skin changes), there is no indication for invasive treatment.

Dr Lobastov. Still, there is no clear consensus on the indication for interventional treatment of iliocaval venous obstruction. However, most recent guidelines suggest treating only symptomatic forms of chronic venous disease (CVD) with severe symptoms and signs, including clinical classes of C3-6 by CEAP and patients with venous claudication.5-8 For individuals with pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS), venous stenting may be suggested for symptomatic improvement, especially if embolization of gonadal veins (GVs) is not effective.9 Limited evidence suggests improved clinical outcomes regarding chronic pelvic pain in women with PCS, nonthrombotic iliac vein lesion (NIVL), and gonadal reflux who were stented in adjunction or instead of embolization.10,11 However, the data on the association of PCS with IVC obstruction (particularly, agenesis) is limited, and a best treatment approach is not developed.12,13 So, in the absence of severe symptoms of CVD and PCS, stenting should be avoided.

Dr Geroulakos. IVC stenting is effective and safe in the majority of patients. An uncommon immediate complication is proximal stent migration. Intermediate complications include contralateral leg DVT secondary to the jailing of blood in unilateral iliac stents extending to the IVC and in-stent stenosis secondary to intima hyperplasia.

Dr Kan. IVC stenting is a safe procedure in this era, but the vein must be recanalized safely first. The technical success rates for iliac vein and IVC endovascular procedures— whether for nonthrombotic lesions, thrombotic lesions, or chronic postthrombotic lesions—are all high, ranging from 94% to 96%. Major bleeding complication rates range from 0.3% to 1.1%, pulmonary embolism from 0.2% to 0.9%, periprocedural mortality from 0.1% to 0.7%, and early thrombosed rates from 1.0% to 6.8%.14

The stenting of complex lesions involving both iliac veins and IVC is sometimes challenging. Multiple stents might be needed to recreate a bifurcation, which may lead to problems at the bifurcation when one or more stents compete and “crush” the contralateral stent. This issue may be overcome by simultaneously deploying the newer nitinol stents from both sides. A trouser configuration can also be constructed using balloon-expandable stents, as described by de Graaf et al.15 It is essential to recreate the bifurcation slightly higher (2–3 cm) than the natural confluence to avoid excessive angulation of the limbs (particularly the left) as they pass into the common iliac vein (CIV).

Dr Nikolov. IVC stenting is effective and safe for chronic occlusive disease with good midterm outcomes and low reintervention rates.16

Dr Tazi Mezalek. Venous stenting for CVD is increasingly used as more evidence supports these interventions’ safety, efficacy, and durability. The evidence base for IVC stenting consists of predominantly single-center, retrospective, observational studies with a high risk of bias. Nonetheless, the procedure appears safe with few major adverse events, and studies that reported clinical outcomes demonstrate improvement in symptoms and quality of life (QOL).17 However, no devices are currently licensed for use in the IVC, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or prospective registry-based studies with larger patient numbers and standardized outcomes are required to improve the evidence base for this procedure.

Dr Lobastov. The recent systematic review combining data from 33 studies reported a technical success rate of 100% (78%-100%), primary patency of 75% (38%-98%), secondary patency of 91.5% (77%-100%) with 33 major complications (3 pulmonary embolisms, 12 stent migrations, 15 major bleedings, and 3 deaths) in 1575 patients.17 These data suggest that IVC stenting is technically effective and safe. However, the clinical efficacy and impact on QOL still need to be studied in well-controlled randomized clinical triasl (RCTs).

Dr Kan. Understanding the clinical and anatomical variations of the pelvic venous system plays a vital role in the diagnosis and approach to transcatheter management of pelvic varices. The essential features of the GVs are determined by venography of the IVC and pelvic vein (PELV). These features should be considered during endovascular interventions to avoid possible complications.

In the case of IVC occlusion, embolization of the enlarged GV should be done with special care, as it may be the only drainage route. In addition, whenever the GV diameter is greater than 12 mm, there is an increased risk of coil migration into the pulmonary artery, which is one of the major complications of the procedure. Other complications of GV embolization include venous perforation, local phlebitis, DVT, and reactions to the contrast agent.18

Dr Nikolov. Absolutely, the access would be through a jugular vein, and I would perform coil embolization and sclerotherapy. This would affect both the pelvis and the lower limb’s varicose veins. PCS symptoms are more likely to disappear.

Dr Lobastov. There is no clear evidence of GV embolization’s reliability, efficacy, and safety with persistent IVC occlusion. On the one hand, dilated GV may be the primary collateral for the venous outflow from the pelvis, so its occlusion may lead to the exacerbation of PCS and CVD symptoms. On the other hand, well-developed alternative collaterals (lumbar veins) may support reflux and reduce the clinical efficacy of embolization. So, the decision should be made case by case after a precise examination of individual venous anatomy of pelvic and abdominal veins. In general, treating reflux in the presence of occlusion is often not effective.

Dr Dzhenina. Currently, PCS is considered one of the causes of reduced fertility in men. However, no convincing data confirm the relationship between pelvic varicosities or PCS with female infertility and increased risk of miscarriage or other pregnancy complications.19

Actually, this young woman managed to get pregnant and delivered by the time of this publication. Pregnancy occurred within 6 months, and pregravid preparation included folic acid 400 mcg/day and vitamin D 2000 IU/day.

At the onset of pregnancy, the venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk was assessed. Considering postthrombotic changes of pelvic and abdominal veins as a personal history of VTE, the risk of recurrent venous thrombosis was deemed high by a combination of factors. In this regard, half of a therapeutic dose of enoxaparin adjusted by prepregnancy body weight was administered for secondary VTE prevention from the early stages of pregnancy until the onset of labor. Also, the patient regularly used compression stockings of 23 to 32 mm Hg to relieve venous symptoms. There were no complications of pregnancy, bleeding, or VTE recurrences.

By the time of labor, the pregnancy was full-term, and the delivery was physiological without complications. Anticoagulation was resumed on the first day after delivery and continued for 6 weeks postpartum. No complications were observed, and breastfeeding was maintained. The child is now healthy and developing according to age.

Dr Geroulakos. Micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) should be considered for the management of pain and heaviness in lower limbs.

Dr Josnin. Evidence suggests that for women with PCS, conservative treatment with MPFF is associated with improved QOL and reduced symptom severity.20,21

Dr Kan. MPFF, a venoactive drug, has been widely investigated in PCS.20-23 All studies demonstrated that MPFF 1000 mg daily reduced the severity of pelvic symptoms, such as pain, heaviness, and labia majora swelling secondary to pelvic varicose veins. Additionally, it was shown that a double dose of MPFF (1000 mg twice daily) in the first month of treatment provides a quicker resolution of symptoms.24 Interestingly, MPFF also reduces chronic pelvic pain caused by prostatitis due to increased venous return through the perineum.25

Dr Tazi Mezalek. Several authors suggest conservative medical management as a first-line therapy in PCS or pelvic venous insufficiency.26 The data are limited as they come from small, randomized trials. Women treated with goserelin, medroxyprogesterone acetate, or an etonogestrel implant reported improved pain and venography scores. MPFF has been shown to decrease the severity of the clinical manifestations in some reports of pelvic varicose veins. Patients who do not respond to medical therapy can pursue invasive treatment, embolization being the gold standard in treating those cases.

Dr Lobastov. Chronic pelvic pain is the most common symptom of PCS.27,28 The true origin of it is still under investigation. However, several neurobiological factors have been discovered, including calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P.29-31 Among all conservative approaches, MPFF demonstrated high clinical efficacy in reducing chronic pelvic pain and pain syndrome after embolization.26,32 So, using MPFF is advocated to improve PCS symptoms and relieve CVD symptoms.

Dr Geroulakos. In this scenario, foam sclerotherapy is the preferred treatment option for recurrent varicose veins.

Dr Josnin. Before anything else, a complete exploration of the deep venous network is essential. I would perform a magnetic resonance venography (MRV) and then, if possible, treat with endovenous laser and phlebectomy if necessary. I would not do sclerotherapy in this patient because of the thrombotic risk.

Dr Kan. To treat varicose veins with some swelling in the lower extremities, I would first do CT venography or MRV to understand the anatomy of the entire vein and determine the best treatment strategy for the patient. If the varicose veins are related to the saphenous trunk problem, I would do endovenous ablation or surgical ligation and stripping. If the only lesion is limited to superficial veins, I would do a local phlebectomy or sclerotherapy.

Dr Nikolov. For that particular case, the preferable treatment option would first be embolization of both GVs and sclerotherapy or miniphlebectomy for lower-limb varicose veins.

Dr Tazi Mezalek. Varicose veins are dilated, twisty veins close to the skin’s surface that usually occur in the legs, caused by chronic venous insufficiency. Varicose veins can be painful, itchy, and unsightly, especially when standing and walking. Occasionally, they may result in complications like ulcers on the leg. Traditionally, surgery was used to remove the pathological vein. Several treatments have emerged using endovenous laser ablation therapy (EVLT), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS), or cyanoacrylate embolization (CAE). Still, heat-based endovenous therapy with a laser may be more effective than traditional surgery and can effectively prevent the recurrence of varicose veins in the longer term.

Dr Lobastov. Considering complete removal of the GSV trunk without any stump with the previous open surgery and connection between thigh and perineal veins, UGFS and ambulatory phlebectomy to remove recurrent varicose veins are methods of choice. Also, local procedures for varicose veins and related pelvic escape points are recommended for patients with varicose veins of pelvic origin.8 In practice, considering the gentle skin of the perineal zone and attempts to close escape points, UGFS may be preferable. However, it is essential to discuss with the patient the risk of further progression of pelvic venous disease and early recurrence of varicose veins in the presence of untreated iliocaval obstruction and GV reflux.

Conclusion

• Obstruction of IVC is a rare but known reason for the development of pelvic congestion syndrome.

• IVC stenting is a well-established intervention with good technical outcomes and a low rate of complications but is often challenging and resource consuming. It is indicated in patients with severe symptoms and signs of CVD. Venous stenting to improve symptoms of PCS is under debate.

• The decision to embolize GVs in the presence of untreated IVC obstruction should be discussed case by case after the precise evaluation of the anatomy of the pelvis and abdominal veins. The primary role of GV in venous outflow from the pelvis should be excluded to avoid the exacerbation of PCS and CVD.

• There is no clear evidence that PCS affects fertility or pregnancy outcomes in women.

• MPFF effectively reduces pelvic pain associated with PCS. It could be used in patients with pelvic venous insufficiency to control symptoms of CVD and PCS.

• UGFS and ambulatory phlebectomy could be used to remove varicose veins of pelvic origin. However, the risk of further progression of PCS and varicose veins recurrence in the presence of pelvic venous insufficiency has not been estimated.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Kirill Lobastov

Department of General Surgery, Pirogov Russian

National Research Medical University, Ostrovitianova

str. 1, Moscow, 117997, Russian Federation

email: lobastov_kv@hotmail.com

References

1. Lurie F, Passman M, Meisner M, et al. The 2020 update of the CEAP classification system and reporting standards. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(3):342-352.

2. Meissner MH, Khilnani NM, Labropoulos N, et al. The Symptoms-Varices Pathophysiology classification of pelvic venous disorders: a report of the American Vein & Lymphatic Society International Working Group on Pelvic Venous Disorders. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(3):568-584.

3. Grøtta O, Enden T, Sandbæk G, et al. Patency and clinical outcome after stent placement for chronic obstruction of the inferior vena cava. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;54(5):620-628.

4. Garg N, Gloviczki P, Karimi KM, et al. Factors affecting outcome of open and hybrid reconstructions for nonmalignant obstruction of iliofemoral veins and inferior vena cava. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(2):383-393.

5. Gloviczki P, ed. Handbook of Venous and Lymphatic Disorders: Guidelines of the American Venous Forum. CRC Press; 2017.

6. ACP Guidelines Committee. Practice guidelines: management of obstruction of the femoroiliocaval venous system. Published 2015. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://www.myavls.org/assets/ pdf/Management-of-Obstruction-of the-Femoroiliocaval-Venous-System Guidelines.pdf

7. Nicolaides A, Kakkos S, Baekgaard N, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs. Guidelines According to Scientific Evidence. Part II. Int Angiol. 2020;39(3):175-240.

8. De Maeseneer MG, Kakkos SK, Aherne T, et al. Editor’s choice – European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2022 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Venous Disease of the Lower Limbs. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022;63(2):184-267.

9. Antignani PL, Lazarashvili Z, Monedero JL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: UIP consensus document. Int Angiol. 2019;38(4):265-283.

10. Santoshi RKN, Lakhanpal S, Satwah V, Lakhanpal G, Malone M, Pappas PJ. Iliac vein stenosis is an underdiagnosed cause of pelvic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6(2):202- 211.

11. Lakhanpal G, Kennedy R, Lakhanpal S, Sulakvelidze L, Pappas PJ. Pelvic venous insufficiency secondary to iliac vein stenosis and ovarian vein reflux treated with iliac vein stenting alone. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(5):1193- 1198.

12. Menezes T, Haider EA, Al-Douri F, El Khodary M, Al-Salmi I. Pelvic congestion syndrome due to agenesis of the infrarenal inferior vena cava. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14(1):36-40.

13. Singh SN, Bhatt TC. Inferior vena cava agenesis: a rare cause of pelvic congestion syndrome. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(3):TD06-TD08.

14. Razavi MK, Jaff MR, Miller LE. Safety and effectiveness of stent placement for iliofemoral venous outflow obstruction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):e002772.

15. de Graaf R, de Wolf M, Sailer AM, van Laanen J, Wittens C, Jalaie H. Iliocaval confluence stenting for chronic venous obstructions. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38(5):1198-1204.

16. Fatima J, AlGaby A, Bena J, Abbasi MN, Clair DG. Technical considerations, outcomes, and durability of inferior vena cava stenting. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2015;3(4):380-388.

17. Morris RI, Jackson N, Smith A, Black SA. A systematic review of the safety and efficacy of inferior vena cava stenting. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2023;65(2):298- 308.

18. Corrêa MP, Bianchini L, Saleh JN, Noel RS, Bajerski JC. Pelvic congestion syndrome and embolization of pelvic varicose veins. J Vasc Bras. 2019;18:e20190061.

19. Galea M, Brincat MR, Calleja-Agius J. A review of the pathophysiology and evidence-based management of varicoceles and pelvic congestion syndrome. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2023:1-12.

20. Akhmetzianov RV, Bredikhin RA. Clinical efficacy of conservative treatment with micronized purified flavonoid fraction in female patients with pelvic congestion syndrome. Pain Ther. 2021;10(2):1567- 1578.

21. Gavrilov SG, Moskalenko YP, Karalkin AV. Effectiveness and safety of micronized purified flavonoid fraction for the treatment of concomitant varicose veins of the pelvis and lower extremities. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(6):1019-1026.

22. Simsek M, Burak F, Taskin O. Effects of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (Daflon) on pelvic pain in women with laparoscopically diagnosed pelvic congestion syndrome: a randomized crossover trial. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2007;34(2):96-98.

23. Tsukanov YT, Tsukanov AY, Levdanskiy EG. Secondary varicose small pelvic veins and their treatment with micronized purified flavonoid fraction. Int J Angiol. 2015:121- 127.

24. Gavrilov SG, Karalkin AV, Moskalenko YP, Grishenkova AS. Efficacy of two micronized purified flavonoid fraction dosing regimens in the pelvic venous pain relief. Int Angiol. 2021;40(3):180-186.

25. Bałabuszek K, Toborek M, Pietura R. Comprehensive overview of the venous disorder known as pelvic congestion syndrome. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):22-36.

26. Gavrilov SG, Turischeva OO. Conservative treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: indications and opportunities. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(6):1099-1103.

27. Herrera-Betancourt AL, Villegas-Echeverri JD, López-Jaramillo JD, López-Isanoa JD, Estrada-Alvarez JM. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical findings for the diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome in women with chronic pelvic pain. Phlebology. 2018;33(5):303-308.

28. Borghi C, Dell’Atti L. Pelvic congestion syndrome: the current state of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(2):291-301.

29. Gavrilov SG, Vassilieva GY, Vasilev IM, Grishenkova AS. The role of vasoactive neuropeptides in the genesis of venous pelvic pain: a review. Phlebology. 2020;35(1):4-9.

30. Gavrilov SG, Vasilieva GY, Vasiliev IM, Efremova OI. Calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P as predictors of venous pelvic pain. Acta Naturae. 2019;11(4):88-92.

31. Gavrilov SG, Karalkin AV, Mishakina NY, Grishenkova AS. Hemodynamic and neurobiological factors for the development of chronic pelvic pain in patients with pelvic venous disorder. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2023;11(3):610-618.e3.

32. Jaworucka-Kaczorowska A. Conservative treatment of pelvic venous disease. Turk J Vasc Surg. 2021;30(suppl 1):S37-S43.